Mariner Jupiter-Saturn

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Voyager program. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2024. |

The Mariner Jupiter-Saturn (also Mariner Jupiter-Saturn-Uranus[1], MJS, or MJSU) mission, part of the Mariner program, was a proposed NASA mission aimed to deploy two probes to explore Jupiter, Saturn, Saturn's moon, Titan, Uranus, and Neptune. The mission originated from the Grand Tour program, conceptualized by Gary Flandro in 1964, which leveraged a rare planetary alignment occurring once every 175 years.[2] The mission was later replaced by the Voyager program in March 1977 due to discrepancies with previous Mariner missions.

History[edit]

The Mariner Jupiter-Saturn mission originated from the Grand Tour program, initially designed to dispatch two probes to explore the outer planets of the Solar System, including Pluto. In 1964, aerospace engineer Gary Flandro identified a rare planetary alignment that allowed a single probe to visit multiple outer planets. The mission gained momentum in 1966 when it was endorsed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. However, in December 1971, the Grand Tour mission was canceled when funding was redirected to the Space Shuttle program.[3]

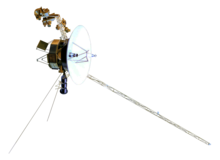

In 1972, the Mariner Jupiter-Saturn mission was proposed, utilizing a spacecraft derived from the Mariner series, initially intended as the 11th Mariner series. The spacecraft was outfitted with 11 scientific instruments designed for detailed exploration. The spacecraft communicated using X-band and S-band microwave frequencies, ensuring stable connections over distances up to 20 astronomical units (AU). Each spacecraft was also equipped with a high-gain antenna and a set of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) to power the mission's operations.[4] That same year, Pioneer 10 detected radiation levels a thousand times more intense than anticipated. As a result, kitchen-grade aluminum foil was applied to specific cables to prevent radiation damage. NASA Office of Space Science, led by S. Ichtiaque Rasool, decided to equip the probe with a plasma wave experiment to study the interaction of solar wind with the magnetic fields and atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn.[3] Kitchen-grade aluminum foil was also applied to specific cables to prevent radiation damage.[5]

The mission aimed to launch two identical spacecraft into trajectories that would enable them to reach all designated outer planets the probes were assigned. With attitude control systems and maneuver thrusters, the probes could adjust their orientation and correct their trajectory as needed, ensuring accurate arrival at their intended destinations. The gravity-assist technique, successfully demonstrated by Mariner 10, would be used to achieve significant velocity changes by maneuvering through an intermediate planet's gravitational field to minimize time towards Saturn.[4]

Two mission trajectories were established: JST aimed at Jupiter, Saturn, and enhancing a Titan flyby, while JSX served as a contingency plan. JST focused on a Titan flyby, while JSX provided a flexible mission plan. If JST succeeded, JSX could proceed with the Grand Tour, but in case of failure, JSX could be redirected for a separate Titan flyby, forfeiting the Grand Tour opportunity.[4] The second probe, now Voyager 2, followed the JSX trajectory, granting it the option to continue on to Uranus and Neptune. Upon Voyager 1 completing its main objectives at Saturn, Voyager 2 received a mission extension, enabling it to proceed to Uranus and Neptune. This allowed Voyager 2 to diverge from the originally planned JST trajectory.[3]

The probes would be launched in August or September 1977, with their main objective being to compare the characteristics of Jupiter and Saturn, such as their atmospheres, magnetic fields, particle environments, ring systems, and moons. They would fly by planets and moons in either a JST or JSX trajectory. After completing their flybys, the probes would communicate with Earth, relaying vital data using their magnetometers, spectrometers, and other instruments to detect interstellar, solar, and cosmic radiation. Their radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) would limit the maximum communication time with the probes to roughly a decade. Following their primary missions, the probes would continue to drift into interstellar space.[4]

Voyager[edit]

On March 4, 1977, NASA announced a competition to rename the mission, believing the existing name was not appropriate as the mission had differed significantly from previous Mariner missions. Voyager was chosen as the new name, referencing an earlier suggestion by William Pickering, who had proposed the name Navigator. Due to the name change occurring close to launch, the probes were still occasionally referred to as Mariner 11 and Mariner 12, or Voyager 11 and Voyager 12.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ "The Voyagers: An unprecedented on-going mission of exploration". NASASpaceFlight.com. Jeff Goldader, Chris Gebhardt. 7 August 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Flandro, Gary (1966). "Fast Reconnaissance Missions to the Outer Solar System Using Energy Derived from the Gravitational Field of Jupiter" (PDF). Astronautica Acta. 12: 329–337.

- ^ a b c d Butrica, Andrew J. (1998). "Voyager: The Grand Tour of Big Science". In Mack, Pamela E. (ed.). From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 978-1-4102-2531-3. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ^ a b c d Smurmeier, H. M. (1 April 1974). "The Mariner Jupiter/Saturn 1977 Mission" (1974)". Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Preview Screening: The Farthest – Voyager in Space". informal.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA Museum Alliance. August 2017. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

supermarket aluminum foil added at the last minute to protect the craft from radiation