String Quartet No. 6 (Bartók)

| String Quartet | |

|---|---|

| No. 6 | |

| by Béla Bartók | |

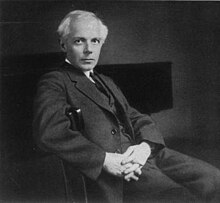

The composer in 1927 | |

| Catalogue |

|

| Composed | 1939 |

| Dedication | Kolisch Quartet |

| Performed | 20 January 1941: New York City |

| Published | 1941 |

| Movements | four |

The String Quartet No. 6 in D minor, Sz. 114, BB 119, was the final string quartet that Béla Bartók wrote before his death in 1945.

The composition of the piece came at a very tumultuous time in the composer's life. With the outbreak of World War II and his mother's illness, Bartók returned to Budapest, where the quartet was finished in November. After his mother's death, Bartók decided to leave with his family for the United States.[1][2][3] Additionally, he began experiencing pain in his right shoulder, which have been speculated as being early signs of the blood disorder that would eventually take his life.[4] Due to the war, communication between Bartók and Székely was difficult, and the quartet was not premiered until 20 January 1941, when the Kolisch Quartet, to whom the work is dedicated, gave its premiere at the Town Hall in New York City.[5][6] The quartet represents a departure from his previous two quartets, with a four movement scheme rather than the five movements of the previous two.[4] Each movement of the piece begins with a slow introduction, which contributes to the nostalgic tone of the piece.[7]

Background[edit]

The string quartet was begun in August 1939 in Saanen, Switzerland, where Bartók was a guest of his patron, the conductor Paul Sacher. Shortly after he completed the Divertimento for String Orchestra on the 17th, he started on a commission for his friend, the violinist Zoltán Székely. Székely was acting as intermediary for the New Hungarian Quartet, who had given the Budapest premiere of the String Quartet No. 5.[5]

During the composition of the piece, the Second World War began. After Germany's annexation of Austria in 1938, it became difficult for Bartók to get his works published, and, by extension, to receive royalties from them. This led to the composer seeking a publishing contract with Boosey & Hawkes.[9] In addition to the state of the world being tumultuous so too was the composer's life. In December 1939, after the completion of the quartet, Bartók learned of his mother's death.[10] Bartók then decided to leave with his family for the United States. Additionally, his own health began to fail.[9] The early signs of a blood disorder began showing for which Bartók would undergo hydrotherapy.[9] It can be seen from Bartók's sketches that he had intended the last movement to have a quick, Romanian folk dance-like character with an aksak rhythmic character, but he abandoned this plan, whether motivated by pure compositional logic or despair at the impending death of his mother and the unfolding catastrophe of the war.

Movements[edit]

The work is in four movements:

- Mesto – Più mosso, pesante – vivace

- Mesto – Marcia

- Mesto – Burletta – moderato

- Mesto[2]

The String Quartet No. 6 does not feature the five movement arch form used in Bartók's fourth and fifth string quartets. Each movement opens with a slow melody marked mesto (mournful). This material is employed for only a relatively short introduction in the first movement, but is longer in the second and longer again in the third. The introduction of the first movement is stated by the viola.[11] It begins each movement of the quartet, but with variations in texture and harmony.[11] The overall form of the piece shows the influence of Gustav Mahler. Musicologists have suggested that the overall form of the piece resembles that of Mahler's Ninth Symphony.[4] In the fourth movement, the mesto material, with reminiscences of the first movement material, consumes the entire movement.

Movement 1: Più mosso, pesante[edit]

This movement begins with a slow introduction by the viola alone marked "Mesto." The movement derives its material from this slow introduction to make a sort of sonata allegro form in D minor.[12] This structure may reflect the influence of Gustav Mahler, for it resembles the beginning of Gustav Mahler's Tenth Symphony with an introduction with a viola solo that is highly chromatic.[4]

Movement 2: Marcia[edit]

This movement begins with a slow "Mesto" introduction as well. However, rather than the theme being presented by a single instrument (in the first movement's case the viola), the theme is presented by all four members of the quartet. For this movement the theme is presented almost in a canonic form. This form permeates throughout the entirety of the movement, with instruments pairing off and playing similar gestures in the beginning of the movement.[12] M. 35 of the movement is an example of this variation of texture and pairing, wherein Bartók pairs both violins together and the viola and cello together. The two violins play an ascending gesture, while the viola and cello play the same gesture inverted. Bartók would later go on to explore instrumental pairing on a much larger scale in his Concerto for Orchestra which was premiered in 1944.

Movement 3: Burletta[edit]

The movement again begins with the "Mesto" theme, this time in a slightly thinner texture than in the previous movement with three of the members of the quartet. This version of the slow introduction also features canonic elements, like in m. 7. The viola enters in m. 10, providing a harmony of stacked thirds.[11] It seems that Bartók uses similar devices in this movement as the previous. After the slow introduction, Bartók pairs different instruments off again, as seen in m. 26. The movement also features different pizzicato effects as well as quarter-tone slides in mm. 26-29, giving the movement a humorous slant.[12]

In poor health and financially insecure, Bartók composed relatively little in the United States before his death in 1945,[13] but, in the last year or so of his life, he made some sketches hypothesized to be the slow movement of a never completed seventh quartet.[14]

Movement 4: Mesto[edit]

This movement is in contrast to the previous three movements in that the mesto theme that had previously been relegated to a slow introduction now permeates the entire movement.[11] Thematic material form the first movement also returns. However, that material is stretched and extended in length. Bartók originally intended to have a fast fourth movement which was supposed to recall his piece Contrasts from the previous year.[12]

Reception/Aftermath[edit]

The quartet was published in 1941 by Boosey & Hawkes.[15] The quartet was premiered on January 20, 1941 in New York City. In the year before the premier, Bartók had permanently moved to the United States with his wife.[7] After the composition of the quartet, a period of low productivity ensued for Bartók.[7] Financially unstable and with the couple's piano duet concerts receiving unfavorable reviews, Bartók began work in ethnomusicology in addition to concert tours in the United States. In the last year or so of his life, he made some sketches hypothesized to be the slow movement of a never completed seventh quartet.[16]

Discography[edit]

| Year | Performers | Label | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Juilliard String Quartet | Sony Classical - 19439831102 | |

| 1963 | Juilliard String Quartet | Sony Classical - 5062312 | [17] |

Sources[edit]

- ^ Kárpáti, János (1994). Bartók's Chamber Music. Pendragon Press. p. 459. ISBN 9780945193197.

- ^ a b Keller, James M. (2011). Chamber Music: A Listener's Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780195382532.

- ^ Suchoff, Benjamin (2004). Béla Bartók: A Celebration. Scarecrow Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780810849587.

- ^ a b c d Griffiths, Paul (1984). Bartók. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- ^ a b Cooper, David (2015). Béla Bartók. Yale University Press. p. 315. ISBN 9780300148770.

- ^ "Bartok Quartet heard in premiere". New York Times. January 21, 1941. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c Sadie, Stanley (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

- ^ a b White, John D. (1976). The Analysis of Music, p.8. ISBN 013033233X.

- ^ a b c Grove, George (1946). Grove's Dictionary of music and musicians. Macmillan. OCLC 970979776.

- ^ Griffiths, Paul (1984). Bartók. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- ^ a b c d Bayley, Amanda (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Bartók. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d Gillies, Malcolm (1993). The Bartók Companion. Amadeus Press.

- ^ Straus, Joseph N. (24 March 2011). Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music (95 ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199766451.

- ^ Somfai, László (7 May 1996). Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources. University of California Press. p. 319. ISBN 9780520914612.

- ^ Crocker, Richard L. (5 May 2014). A History of Musical Style. Courier Corporation. p. 553. ISBN 9780486173245.

- ^ Lesznai, Lajos (1973). Bartók. J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- ^ Juillard String Quartet, Bartók – The Complete String Quartets (2002, CD), retrieved 2022-09-17