Damask

Damask (/ˈdæməsk/; Arabic: دمشق) is a woven, reversible patterned fabric. Damasks are woven by periodically reversing the action of the warp and weft threads[1]. The pattern is most commonly created with a warp-faced satin weave and the ground with a weft-faced or sateen weave[2]. Fabrics used to create damasks include silk, wool, linen, cotton, and synthetic fibers, but damask is best shown in cotton and linen[3]. Over time, damask has become a broader term for woven fabrics with a reversible pattern, not just silks[4].

There are a few types of damask: true, single, compound, and twill. True damask is made entirely of silk[5]. Single damask has only one set of warps and wefts and thus is made of up to two colors. Compound damask has more than one set of warps and wefts and can include more than two colors[5]. Twill damasks include a twill-woven ground or pattern[6].

History[edit]

A damask weave is one of the five basic weaving techniques—the others being tabby, twill, Lampas, and tapestry—of the early Middle Ages Byzantine and Middle Eastern weaving centers. Damask was named after the city Damascus, Syria a large trading center on the Silk Road[7].

Damask in China[edit]

In China, draw looms with a large number of heddles were developed to weave damasks with complicated patterns.[8] The Chinese may have produced damasks as early as the Tang dynasty (618–907).[9] Damasks became scarce after the 9th century outside Islamic Spain, but were revived in some places in the 13th century. Trade logs between The British East India Company and China often demonstrate an ongoing trade of Chinese silks, especially damask.[10] Damask is documented as being the heaviest Chinese silk.[10]

Damask in Europe[edit]

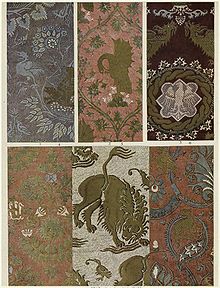

The word damask first appeared in a Western European language in mid-14th century French records.[11] Shortly after its appearance in French language, damasks were being woven on draw looms in Italy. From the 14th to 16th century, most damasks were woven in one colour with a glossy warp-faced satin pattern against a duller ground. Two-colour damasks had contrasting colour warps and wefts and polychrome damasks added gold and other metallic threads or additional colours as supplemental brocading wefts. Medieval damasks were usually woven in silk, but weavers also produced wool and linen damasks.[12]

Damask and Nomads[edit]

In daily nomadic life this form of weaving was generally employed by women, specifically in occupations such as carpet-making[13]. Women collected raw material from pasture animals and dyes from local flora, such as berries, insects, or grasses, to use in production[13]. Each woman would create a specialized pattern sequence and color scheme that aligned with her personal identity and ethnic group[13]. These techniques were passed down generationally from mother to daughter[13].

Modern usage[edit]

In the 19th century, the invention of the Jacquard loom which was automated with a system of punched cards, made weaving damask faster and cheaper.[8]

Modern damasks are woven on computerized Jacquard looms.[14] Damask weaves are commonly produced in monochromatic (single-colour) weaves in silk, linen or synthetic fibres such as rayon and feature patterns of flowers, fruit and other designs. The long floats of satin-woven warp and weft threads cause soft highlights on the fabric which reflect light differently according to the position of the observer. Damask weaves appear most commonly in table linens and furnishing fabrics, but they are also used for clothing.[8] The damask weave is prevalent in the fashion industry due to its versatility and high-quality finish. Damask is often used for mid-to-high-quality garments--associating itself with higher quality brands/labels.

See also[edit]

- Diapering (damask patterns in heraldry)

References[edit]

- ^ Reath, N. A.; Jayne, Horace H. F. (1924). "A Classification of Hand-Loom Fabrics". Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum. 20 (89): 23–34. doi:10.2307/3794229. ISSN 0891-3609. JSTOR 3794229.

- ^ Kadolph, Sara J. (2007). Textiles (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-118769-6. OCLC 65197813.

- ^ Reath, N. A.; Jayne, Horace H. F. (1924). "A Classification of Hand-Loom Fabrics". Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum. 20 (89): 23–34. doi:10.2307/3794229. ISSN 0891-3609. JSTOR 3794229.

- ^ "Damask | Damask Weaving, Silk Fabric, Jacquard Loom | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ a b "Damask | Damask Weaving, Silk Fabric, Jacquard Loom | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Dimitrova, Kate (2009-10-22). "Kate Dimitrova. Review of "Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings, 1300–1550" by Lisa Monnas". Caa.reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2009.107. ISSN 1543-950X.

- ^ Jenkins, David T., ed.: The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-34107-8, p. 343.

- ^ a b c Gillow, John (1999). World Textiles: A Visual Guide to Traditional Techniques. Thames & Hudson. p. 82. ISBN 0-500-28247-1.

- ^ "A World of Looms: Weaving Technology and Textile Arts in China and Beyond". China National Silk Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ a b Lee-Whitman, Leanna (1982). "The Silk Trade: Chinese Silks and the British East India Company". Winterthur Portfolio. 17 (1): 21–41. doi:10.1086/496066. ISSN 0084-0416. JSTOR 1180762.

- ^ "Damas" etymology (in French). www.cnrtl.fr accessed 2 March 2021

- ^ Monnas, Lisa. Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings 1300–1550. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 295–299

- ^ a b c d Mozzati, Luca; Radzinowicz, David (2019). Islamic art (Compact ed.). Munich: Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-8566-2. OCLC 1121577357.

- ^ Kadolph, Sara J., ed.: Textiles, 10th edition, Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2007, ISBN 0-13-118769-4, p. 251