Rye

| Rye | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Genus: | Secale |

| Species: | S. cereale

|

| Binomial name | |

| Secale cereale | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Secale fragile M.Bieb. | |

Rye (Secale cereale) is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is grown principally in an area from eastern and northern Europe into Russia. It is much more tolerant of cold weather and poor soil than other cereals, making it useful in those regions; its vigorous growth suppresses weeds, and provides abundant forage for animals early in the year. It is a member of the wheat tribe (Triticeae) which includes the cereals wheat and barley. Rye grain is used for bread, beer, rye whiskey, and animal fodder. In Scandinavia, rye was a staple food in the Middle-ages, and rye crispbread remains a popular food in the region. Around half of world production is in Europe; relatively little is traded between countries. A wheat-rye hybrid, triticale, combines the qualities of the two parent crops and is produced in large quantities worldwide. In European folklore, the Roggenwolf ("rye wolf") is a carnivorous corn demon or Feldgeist.

Origins[edit]

The rye genus Secale is in the grass tribe Triticeae, which contains other cereals such as barley (Hordeum) and wheat (Triticum).[1]

The generic name Secale, related to Italian segale and French seigle, is of unknown origin but may derive from a Balkan language.[2] The English name rye derives from Old English ryge, related to Dutch rogge, German Roggen, Russian rozh.[3]

Rye is one of several cereals that grow wild in the Levant, central and eastern Turkey and adjacent areas. Evidence uncovered at the Epipalaeolithic site of Tell Abu Hureyra in the Euphrates valley of northern Syria suggests that rye was among the first cereal crops to be systematically cultivated, around 13,000 years ago.[4] However, that claim remains controversial; critics point to inconsistencies in the radiocarbon dates, and identifications based solely on grain, rather than on chaff.[5]

Domesticated rye occurs in small quantities at a number of Neolithic sites in Asia Minor (Anatolia, now Turkey), such as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Can Hasan III near Çatalhöyük,[6][7] but is otherwise absent from the archaeological record until the Bronze Age of central Europe, c. 1800–1500 BCE.[8]

It is likely that rye was brought westwards from Asia Minor as a secondary crop, meaning that it was a minor admixture in wheat as a result of Vavilovian mimicry, and was only later cultivated in its own right.[9] Archeological evidence of this grain has been found in Roman contexts along the Rhine and the Danube and in Ireland and Britain.[10] Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder was dismissive of a grain that may have been rye, writing that it "is a very poor food and only serves to avert starvation".[11] He said it was mixed with spelt "to mitigate its bitter taste, and even then is most unpleasant to the stomach".[12]

Description[edit]

Rye is a tall grass grown for its seeds; it can be an annual or a biennial. Depending on environmental conditions and variety it reaches 1 to 3 metres (3 ft 3 in to 9 ft 10 in) in height. Its leaves are blue-green, long, and pointed. The seeds are carried in a curved head or spike some 7 to 15 centimetres (2.8 to 5.9 in) long. It is composed of many spikelets, each of which holds two small flowers; the spikelets alternate left and right up the head.[13]

-

Botanical illustration

-

Seed in husk

-

Different types of grains

-

The seeds of rye are some 7 or 8 mm long, much larger and less round than wheat.

Cultivation[edit]

Since the Middle Ages, people have cultivated rye widely in Central and Eastern Europe. It serves as the main bread cereal in most areas east of the France–Germany border and north of Hungary. In Southern Europe, it was cultivated on marginal lands.[14]

Rye grows well in much poorer soils than those necessary for most cereal grains. Thus, it is an especially valuable crop in regions where the soil has sand or peat. Rye plants withstand cold better than other small grains do. Rye will survive with snow cover that would otherwise result in winter-kill for winter wheat. Most farmers grow winter ryes, which are planted and begin to grow in autumn. In spring, the plants develop and produce their crop.[15] Winter rye, planted in the autumn, grows rapidly, allowing it to provide spring grazing, at a time when spring-planted wheat has only just germinated.[16]

The physical properties of rye affect attributes of the final food product such as seed size, surface area, and porosity. The surface area of the seed directly correlates to the drying and heat transfer time.[17] Smaller seeds have increased heat transfer, which leads to lower drying time. Seeds with lower porosity lose water more slowly during the process of drying.[17]

Rye is harvested like wheat with a combine harvester, which cuts the plants, threshes and winnows the grain, and releases the straw to the field where it is later pressed into bales or left as soil amendment. The resultant grain is stored in local silos or transported to regional grain elevators and combined with other lots for storage and distant shipment. Before the era of mechanised agriculture, rye harvesting was a manual task performed with scythes or sickles.[18][19]

Agroecology[edit]

Winter rye is any breed of rye planted in the autumn to provide ground cover for the winter. It grows during warmer days of the winter when sunlight temporarily warms the plant above freezing, even while there is general snow cover. It can be used as a cover crop to prevent the growth of winter-hardy weeds.[20]

Rye grows better than any other cereal in heavy clay and light sandy soil, and infertile or drought-affected soils. It can tolerate pH between 4.5 and 8.0, but soils having pH 5.0 to 7.0 are best suited for rye cultivation. Rye grows best in fertile, well-drained loam or clay-loam soils.[21]

Rye can thrive in subzero environments. The leaves of winter rye produce various antifreeze polypeptides (different from the antifreeze polypeptides produced by some fish and insects).[22]

Rye is a common, unwanted invader of winter wheat fields. If allowed to grow and mature, it may cause substantially reduced prices (docking) for harvested wheat.[23]

Pests and diseases[edit]

The nematode Ditylenchus dipsaci and a variety of herbivorous insects can seriously affect plant health.[24]

Rye is highly susceptible to the ergot fungus.[25][26] Consumption of ergot-infected rye by humans and animals results in a serious medical condition known as ergotism. Ergotism can cause both physical and mental harm, including convulsions, miscarriage, necrosis of digits, hallucinations and death. Historically, damp northern countries that have depended on rye as a staple crop were subject to periodic epidemics of this condition. Such epidemics have been found to correlate with periods of frequent witch trials, such as the Salem witch trials in Massachusetts in 1692.[15] Modern grain-cleaning and milling methods have practically eliminated the disease, but contaminated flour may end up in bread and other food products if the ergot is not removed before milling.[27]

After an absence of 60 years, stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici) has returned to Europe in the 2020s.[28] Areas affected include Germany, Russia (Western Siberia), Spain, and Sweden.[28]

Production and consumption[edit]

Rye is grown primarily in Eastern, Central and Northern Europe. The main rye belt stretches from northern Germany through Poland, Ukraine, and eastwards into central and northern Russia. Rye is also grown in North America, in South America including Argentina, in Oceania (Australia]] and New Zealand), in Turkey, and in northern China. Production levels of rye have fallen since 1992 in most of the producing nations, as of 2022[update]; for instance, production of rye in Russia fell from 13.9 Mt in 1992 to 2.2 Mt in 2022.[30][31]

| Producer | 2022[31] | 2020[31] | 2018[31] | 2016[31] | 2014[31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7,450,920 | 8,939,510 | 6,141,040 | 7,400,686 | 8,890,726 | |

| 3,132,300 | 3,513,400 | 2,201,400 | 3,173,800 | 3,854,400 | |

| 2,337,130 | 2,929,930 | 2,126,570 | 2,199,578 | 2,792,593 | |

| 2,178,808 | 2,377,629 | 1,916,056 | 2,547,878 | 3,280,759 | |

| 750,000 | 1,050,702 | 502,505 | 650,908 | 867,075 | |

| 691,470 | 699,370 | 476,590 | 577,200 | 677,800 | |

| 520,177 | 487,800 | 236,400 | 436,000 | 217,500 | |

| 500,767 | 512,591 | 504,698 | 545,657 | 520,000 | |

| 314,030 | 456,780 | 393,780 | 391,560 | 478,000 | |

| 312,460 | 292,930 | 214,180 | 290,379 | 182,610 | |

| 242,207 | 72,450 | 95,366 | 48,563 | 55,899 | |

| 225,510 | 221,201 | 86,098 | 60,676 | 52,130 | |

| 188,880 | 407,620 | 404,280 | 377,355 | 290,970 | |

| World total | 13,143,055 | 15,036,812 | 10,702,482 | 12,999,144 | 15,204,158 |

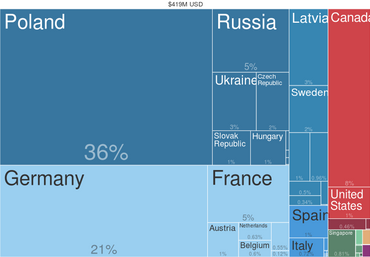

World trade of rye is low compared with other grains such as wheat. The total export of rye for 2016 was $186M[32] compared with $30.1B for wheat.[33]

Poland consumes the most rye per person at 32.4 kg (71 lb) per capita (2009). Nordic and Baltic countries are also very high. The EU in general is around 5.6 kg (12 lb) per capita. The entire world only consumes 0.9 kg (2 lb) per capita.[34]

Nutritional value[edit]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,414 kJ (338 kcal) |

75.86 g | |

| Sugars | 0.98 g |

| Dietary fiber | 15.1 g |

1.63 g | |

10.34 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 25% 0.3 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 23% 0.3 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 25% 4 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 20% 1 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 18% 0.3 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 10% 38 μg |

| Choline | 5% 30 mg |

| Vitamin E | 7% 1 mg |

| Vitamin K | 5% 6 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 2% 24 mg |

| Iron | 17% 3 mg |

| Magnesium | 26% 110 mg |

| Manganese | 130% 3 mg |

| Phosphorus | 27% 332 mg |

| Potassium | 17% 510 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 2 mg |

| Zinc | 27% 3 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 10.6 g |

| Selenium | 14 µg |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[35] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[36] | |

A 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference serving of rye provides 1,410 kilojoules (338 kilocalories) of food energy and is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value [DV]) of essential nutrients, including protein, dietary fiber, the B vitamins, niacin (27% DV) and vitamin B6 (23% DV), and several dietary minerals (table). Highest nutrient contents are for manganese (143% DV) and phosphorus (47% DV).[37]

Health effects[edit]

According to Health Canada and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, consuming at least 4 grams (0.14 oz) per day of rye beta-glucan or 0.65 grams (0.023 oz) per serving of soluble fiber can lower levels of blood cholesterol, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases.[38][39]

Eating whole-grain rye, as well as other high-fibre grains, improves regulation of blood sugar (i.e., reduces blood glucose response to a meal).[40] Consuming breakfast cereals containing rye over weeks to months also improved cholesterol levels and glucose regulation.[41]

Health concerns[edit]

Like wheat, barley, and their hybrids and derivatives, rye contains glutens and related prolamines, which makes it an unsuitable grain for consumption by people with gluten-related disorders, such as celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and wheat allergy, among others.[42] Nevertheless, some wheat allergy patients can tolerate rye or barley.[43]

Ergotism is an illness that can result from eating rye and other grains infected by ergot fungi (which produce ergoline toxins in infected products). Although it is no longer a common illness because of modern food safety efforts, it was common before the 20th century, and remains a risk if food safety vigilance breaks down.[44]

Uses[edit]

Food and drink[edit]

Rye grain is refined into a flour high in gliadin but low in glutenin and rich in soluble fiber. Alkylresorcinols are phenolic lipids present in high amounts in the bran layer (e.g. pericarp, testa and aleurone layers) of wheat and rye (0.1–0.3% of dry weight).[45] Rye bread, including pumpernickel, is made using rye flour and is a widely eaten food in Northern and Eastern Europe.[46][47] In Scandinavia, rye is widely used to make crispbread (Knäckebröd); in the Middle Ages it was a staple food in the region, and it remains popular in the 21st century.[48]

Rye grain is used to make alcoholic drinks, such as rye whiskey and rye beer.[13] The traditional cloudy and sweet-sour low-alcohol beverage kvass is fermented from rye bread or rye flour and malt.[49]

-

Rye bread

-

Swedish rye crispbread (Knäckebröd)

-

Rye whiskey

-

Rye beer

Other uses[edit]

Rye is a useful forage crop in cool climates; it grows vigorously and provides plentiful fodder for grazing animals, or green manure to improve the soil.[50] It forms a good cover crop in winter with its rapid growth and deep roots.[51]

Rye straw is used as livestock bedding, despite the risk of ergot poisoning.[52] It is used on a small scale to make crafts such as corn dollies.[53] More recently it has found uses as a raw material for bioconversion to products such as the sweetener xylitol.[54]

Rye flour is mixed with linseed oil and iron oxide to make traditional Falun red paint, widely used as a house paint in Sweden.[55]

Production of hybrids[edit]

Plant breeders, starting in the 19th century in Germany and Scotland,[56] but mainly from the 1950s, worked to develop a hybrid cereal with the best qualities of wheat and rye, now called triticale. Modern triticales are hexaploid with six sets of chromosomes, and are used to produce millions of tons of cereal annually.[57]

Varieties of rye hold much genetic diversity,[58][59][60] which can be used to improve other crops such as wheat. For example, the pollination abilities of wheat was improved by the addition of the rye chromosome 4R; this increased the size of the wheat anther and the amount of pollen.[61] The 1R chromosome is the source of many crop disease resistance genes.[62] Varieties such as Petkus, Insave, Amigo, and Imperial have donated 1R-originating resistance to wheat.[62] AC Hazlet rye is a medium-sized fall variety rye that showed resistance to both lodging and shattering.[63] Rye was the gene donor of Sr31 – a stem rust resistance gene – introgressed into wheat.[64]

The characteristics of S. cereale have been combined with another perennial rye, S. montanum, to produce S. cereanum, which has the beneficial characteristics of each. The hybrid rye can be grown in harsh environments and on poor soil. It provides improved forage with digestible fiber and protein.[65]

In human culture[edit]

In European folklore, the Roggenwolf ("rye wolf") is a carnivorous corn demon or Feldgeist, a field spirit shaped like a wolf.[66] The Roggenwolf steals children and feeds on them.[67] The last grain heads are often left at their place as a sacrifice for the agricultural spirits.[68]

In contrast, the The Roggenmuhme or Roggenmutter ("rye aunt" or "rye mother") is an anthropomorphic female corn demon with fiery fingers. Her bosoms are filled with tar, and may end in tips of igneous iron. Her bosoms are also long, and as such must be thrown over her shoulders when she runs. The Roggenmuhme is completely black or white, and in her hand she has a birch or whip from which lightning sparks. She can change herself into different animals; such as snakes, turtles, frogs and others.[69]

The classical scholar Carl A. P. Ruck writes that the Roggenmutter was believed to go through the fields, rustling like the wind, with a pack of rye wolves running after her. They spread ergot through the sheaves of harvested rye. According to Ruck, they then lured children into the fields to nurse on the infected grains "like the iron teats of the Roggenmutter".[70] The enlarged reddish ergot-infected grains were known as Wulfzähne (wolf teeth).[70]

References[edit]

- ^ Soreng, Robert J.; Peterson, Paul M.; Romaschenko, Konstantin; et al. (2017). "A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae) II: An update and a comparison of two 2015 classifications". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 55 (4): 259–290. doi:10.1111/jse.12262. ISSN 1674-4918.

- ^ Walde, Alois; Hofmann, Johann Baptist (1954) "secale", in Lateinisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German), 3rd edition, volume 2, Heidelberg: Carl Winter, page 504

- ^ "rye (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Hillman, Gordon; Hedges, Robert; Moore, Andrew; Colledge, Susan; Pettitt, Paul (2001). "New evidence of Lateglacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates". The Holocene. 11 (4): 383–393. Bibcode:2001Holoc..11..383H. doi:10.1191/095968301678302823. S2CID 84930632. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ Colledge, Sue; Conolly, James (2010). "Reassessing the evidence for the cultivation of wild crops during the Younger Dryas at Tell Abu Hureyra, Syria". Environmental Archaeology. 15 (2): 124–138. Bibcode:2010EnvAr..15..124C. doi:10.1179/146141010X12640787648504. S2CID 129087203.

- ^ Hillman, Gordon (1978). "On the Origins of Domestic rye: Secale Cereale: The Finds from Aceramic Can Hasan III in Turkey". Anatolian Studies. 28: 157–174. doi:10.2307/3642748. JSTOR 3642748. S2CID 85225244. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- ^ Sidhu, Jagdeep; Ramakrishnan, Sai Mukund; Shaukat, Ali; Amy, Bernado; Bai, Guihua; Sidrat, Abdullah; Ayana, Girma; Sehgal, Sunish (2019). "Assessing the genetic diversity and characterizing genomic regions conferring Tan Spot resistance in cultivated rye". PLOS ONE. 14 (3): e0214519. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1414519S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214519. PMC 6438500. PMID 30921415.

- ^ Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria; Weiss, Ehud (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-954906-1. Retrieved October 5, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ McElroy, J. Scott (2014). "Vavilovian Mimicry: Nikolai Vavilov and His Little-Known Impact on Weed Science". Weed Science. 62 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1614/ws-d-13-00122.1. S2CID 86549764.

- ^ Gyulai, Ferenc (2014). "Archaeobotanical overview of rye (Secale Cereale L.) in the Carpathian-basin I. from the beginning until the Roman age". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Science. 1 (2): 25–35. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2016. page 26.

- ^ Evans, L. T.; Peacock, W. J. (March 19, 1981). Wheat Science: Today and Tomorrow. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-23793-2. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pliny the Elder (1855) [c. 77–79]. The Natural History. Translated by Bostock, John; Riley, H. T. London: Taylor and Francis (T&F). Book 18, Ch. 40. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2016 – via Perseus Digital Library, Trufts University.

- ^ a b "Rye". PlantVillage. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Behre, Karl-Ernst (1992). "The history of rye cultivation in Europe". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 1 (3). doi:10.1007/BF00191554. ISSN 0939-6314. S2CID 129518700. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Wong, George J. (1998). "Ergot of Rye: History". Botany 135 Syllabus. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Botany Department. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Growing Winter Rye in Scotland". Farm Advisory Service Scotland. May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Jouki, Mohammad; Emam-Djomeh, Zahra; Khazaei, Naimeh (2012). "Physical Properties of Whole Rye Seed (Secale cereal)". International Journal of Food Engineering. 8 (4). doi:10.1515/1556-3758.2054. S2CID 102003836.

- ^ Jensen, Joan M. (1988). Loosening the Bonds: Mid-Atlantic Farm Women, 1750–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press (YUP). p. 47. ISBN 978-0-300-04265-8. Retrieved July 17, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jones, Peter M. (2016). Agricultural Enlightenment: Knowledge, Technology, and Nature, 1750–1840. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP). p. 123. ISBN 978-0-19-102515-0.

- ^ Burgos, Nilda R.; Talbert, Ronald E.; Kuk, Yong In (2006). "Grass-legume mixed cover crops for weed management". In Sing, Harinder P.; Batish, Daisy Rani; Kohli, Ravinder Kumar (eds.). Handbook of Sustainable Weed Management. New York: Haworth Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-56022-957-5. Retrieved October 5, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Willy H. Verheye, ed. (2010). "Growth And Production Of Oat And Rye". Soils, Plant Growth and Crop Production Volume II. EOLSS Publishers. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-84826-368-0. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Hon, W. C.; Griffith, M.; Chong, P.; Yang, D. S.-C. (March 1, 1994). "Extraction and Isolation of Antifreeze Proteins from Winter Rye (Secale cereale L.) Leaves". Plant Physiology. 104 (3): 971–980. doi:10.1104/pp.104.3.971. ISSN 1532-2548. PMC 160695. PMID 12232141.

- ^ Lyon, Drew J.; Klein, Robert N (May 2007) [2002]. "Rye Control in Winter Wheat" (Revised ed.). Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Lincoln Extension. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ Matz, Samuel A. (1991). Chemistry and Technology of Cereals as Food and Feed. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold/AVI. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-442-30830-8. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ ergot Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, online medical dictionary

- ^ ergot, Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Petruzzello, Melissa. "Ergot". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Annika, Djurle; Young, Beth; Berlin, Anna; Vågsholm, Ivar; Blomstrom, Anne; Nygren, Jim; Kvarnheden, Anders (2022). "Addressing biohazards to food security in primary production". Food Security. 14 (6). Springer Nature: 1475–1497. doi:10.1007/s12571-022-01296-7. eISSN 1876-4525. ISSN 1876-4517. S2CID 250250761.

- ^ Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity

- ^ "Crops and livestock products". FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ a b c d e f "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "OEC - Countries that export Rye (2016)". Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ "OEC - Countries that export Wheat except durum wheat, and meslin (2016)". Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ "Statistics and Usage - www.ryeandhealth.org". Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Link to USDA Database Entry

- ^ "21 CFR Part 101 [Docket No. 2004P-0512], Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soluble Dietary Fiber From Certain Foods and Coronary Heart Disease". US Food and Drug Administration. May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Summary of Health Canada's Assessment of a Health Claim about Barley Products and Blood Cholesterol Lowering". Health Canada. July 12, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ Harris KA, Kris-Etherton PM (November 2010). "Effects of whole grains on coronary heart disease risk". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 12 (6): 368–76. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0136-1. PMID 20820954. S2CID 29100975.

- ^ Williams PG (September 2014). "The benefits of breakfast cereal consumption: a systematic review of the evidence base". Advances in Nutrition. 5 (5): 636S–673S. doi:10.3945/an.114.006247. PMC 4188247. PMID 25225349.

- ^ Tovoli, F.; Masi, C.; Guidetti, E.; Negrini, G.; Paterini, P.; Bolondi, L. (March 16, 2015). "Clinical and diagnostic aspects of gluten related disorders". World Journal of Clinical Cases. 3 (3): 275–284. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275. PMC 4360499. PMID 25789300.

- ^ Pietzak, M. (January 2012). "Celiac Disease, Wheat Allergy, and Gluten Sensitivity". Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 36 (1 Suppl): 68S–75S. doi:10.1177/0148607111426276. PMID 22237879.

- ^ Belser-Ehrlich S, Harper A, Hussey J, Hallock R (2013). "Human and cattle ergotism since 1900: symptoms, outbreaks, and regulations". Toxicol Ind Health (Review). 29 (4): 307–16. doi:10.1177/0748233711432570. PMID 22903169. S2CID 26814635.

- ^ Suzuki, Yoshikatsu; Esumi, Yasuaki; Yamaguchi, Isamu (1999). "Structures of 5-alkylresorcinol-related analogues in rye". Phytochemistry. 52 (2): 281–289. Bibcode:1999PChem..52..281S. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00196-X.

- ^ "Grains: Rye" Archived November 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch) bakkerijmuseum.nl

- ^ Prättälä, Ritva; Helasoja, Ville; Mykkänen, Hannu (2000). "The consumption of rye bread and white bread as dimensions of health lifestyles in Finland". Public Health Nutrition. 4 (3): 813–819. doi:10.1079/PHN2000120. PMID 11415489.

- ^ "Tuggmotstånd" [Tough to chew]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Hornsey, Ian Spencer (2012). Alcohol and its Role in the Evolution of Human Society. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 296–300. ISBN 978-1-84973-161-4.

- ^ "Forage Identification: Rye". University of Wyoming: Department of Plant Sciences. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "Winter Rye: A Reliable Cover Crop". University of Vermont. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ "Use caution when using rye straw for bedding". Martin-Gatton College of Agriculture, Food and Environment. June 7, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions - Straw". Straw Craftsmen. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Vallejos, María E.; Area, María C. (2017). "Xylitol as Bioproduct From the Agro and Forest Biorefinery". Food Bioconversion. Elsevier. p. 411–432. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-811413-1.00012-7. ISBN 978-0-12-811413-1.

- ^ "Swedish Red Paint - Falu Röd". Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ "Triticale". Digital Herbarium of Crop Plants Establishment of Digital Herbarium and Herbal museum for Crop plant by Department of Crop Botany, BSMRAU. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ Faccini, Nadia; Morcia, Caterina; Terzi, Valeria; Rizza, Fulvia; Badeck, Franz-Werner (October 4, 2023). "Triticale in Italy". Biology. 12 (10): 1308. doi:10.3390/biology12101308. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 10603945. PMID 37887018.

- ^ Ribeiro, Miguel; Seabra, Luís; Ramos, António; Santos, Sofia; Pinto-Carnide, Olinda; Carvalho, Carlos; Igrejas, Gilberto (April 1, 2012). "Polymorphism of the storage proteins in Portuguese rye (Secale cereale L.) populations". Hereditas. 149 (2): 72–84. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.2012.02239.x. ISSN 1601-5223. PMID 22568702.

- ^ Bauer, Eva; Schmutzer, Thomas; Barilar, Ivan; Mascher, Martin; Gundlach, Heidrun; Martis, Mihaela M.; Twardziok, Sven O.; Hackauf, Bernd; Gordillo, Andres (March 1, 2017). "Towards a whole-genome sequence for rye (Secale cereale L.)". The Plant Journal. 89 (5): 853–869. doi:10.1111/tpj.13436. ISSN 1365-313X. PMID 27888547.

- ^ Rabanus-Wallace, M.; Stein, Nils (2021). The Rye Genome. Springer Nature. pp. 85–100. ISBN 978-3-030-83383-1. which cites Li, Guangwei; Wang, Lijian; Yang, Jianping; et al. (2021). "A high-quality genome assembly highlights rye genomic characteristics and agronomically important genes". Nature Genetics. 53 (4). Nature Portfolio: 574–584. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00808-z. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 8035075. PMID 33737755. S2CID 232298036.

- ^ Nguyen, Vy; Fleury, Delphine; Timmins, Andy; Laga, Hamid; Hayden, Matthew; Mather, Diane; Okada, Takashi (February 26, 2015). "Addition of rye chromosome 4R to wheat increases anther length and pollen grain number". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 128 (5): 953–964. doi:10.1007/s00122-015-2482-4. ISSN 0040-5752. PMID 25716820. S2CID 16421403.

- ^ a b Herrera, Leonardo; Gustavsson, Larisa; Åhman, Inger (2017). "A systematic review of rye (Secale cereale L.) as a source of resistance to pathogens and pests in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)". Hereditas. 154 (1). BioMed Central: 1–9. doi:10.1186/s41065-017-0033-5. ISSN 1601-5223. PMC 5445327. PMID 28559761.

- ^ SeCan. (2014). AC® Hazlet. Retrieved from "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ellis, Jeffrey G.; Lagudah, Evans S.; Spielmeyer, Wolfgang; Dodds, Peter N. (November 24, 2014). "The past, present and future of breeding rust resistant wheat". Frontiers in Plant Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00641. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 4241819. PMID 25505474.

- ^ Sipos, Tamás; Halász, Erika (April 25, 2007). "The role of perennial rye (Secale cereale × S. montanum) in sustainable agriculture". Cereal Research Communications. 35 (2): 1073–1075. doi:10.1556/CRC.35.2007.2.227. ISSN 0133-3720.

- ^ Golther, Wolfgang (2011)Germanische Mythologie: Vollständige Ausgabe. Marix-Verlag, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-937715-38-4 p. 200.

- ^ Mannhardt, Wilhelm (2005) Wald- und Feldkulte: Band II. Elibron Classics, ISBN 1-4212-4778-X p. 319.

- ^ Dahn, Felix; Dahn, Therese (2010) Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Marix-Verlag, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-937715-39-1 p. 171.

- ^ Mannhardt, Wilhelm (2014) Die Korndämonen: Beitrag zur germanischen Sittenkunde. Bremen University Press, Bremen, ISBN 978-3-95562-798-0 p. 20.

- ^ a b Ruck, Carl (2019). "Persia, Haoma and the Greek Mysteries" (PDF). Sexus Journal. 4 (11): 991–1034.