Ovarian cyst

| Ovarian cyst | |

|---|---|

| |

| A simple ovarian cyst of most likely follicular origin | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | None, bloating, lower abdominal pain, lower back pain[1] |

| Complications | Rupture, twisting of the ovary[1] |

| Types | Follicular cyst, corpus luteum cyst, cysts due to endometriosis, dermoid cyst, cystadenoma, ovarian cancer[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Ultrasound[1] |

| Prevention | Hormonal birth control[1] |

| Treatment | Conservative management, pain medication, surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | Usually good[1] |

| Frequency | 8% symptomatic before menopause[1] |

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac within the ovary.[1] Often they cause no symptoms.[1] Occasionally they may produce bloating, lower abdominal pain, or lower back pain.[1] The majority of cysts are harmless.[1][2] If the cyst either breaks open or causes twisting of the ovary, it may cause severe pain.[1] This may result in vomiting or feeling faint,[1] and even cause head aches.

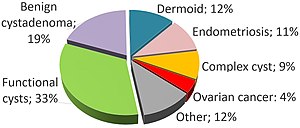

Most ovarian cysts are related to ovulation, being either follicular cysts or corpus luteum cysts.[1] Other types include cysts due to endometriosis, dermoid cysts, and cystadenomas.[1] Many small cysts occur in both ovaries in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).[1] Pelvic inflammatory disease may also result in cysts.[1] Rarely, cysts may be a form of ovarian cancer.[1] Diagnosis is undertaken by pelvic examination with a pelvic ultrasound or other testing used to gather further details.[1]

Often, cysts are simply observed over time.[1] If they cause pain, medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen may be used.[1] Hormonal birth control may be used to prevent further cysts in those who are frequently affected.[1] However, evidence does not support birth control as a treatment of current cysts.[3] If they do not go away after several months, get larger, look unusual, or cause pain, they may be removed by surgery.[1]

Most women of reproductive age develop small cysts each month.[1] Large cysts that cause problems occur in about 8% of women before menopause.[1] Ovarian cysts are present in about 16% of women after menopause, and, if present, are more likely to be cancerous.[1][4]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Ovarian cysts tend to produce non-specific symptoms (i.e., symptoms that could be caused be a large number of conditions).[5] Some or all of the following symptoms may be present, though it is possible not to experience any symptoms:[6]

- Abdominal pain. Dull aching pain within the abdomen or pelvis, especially during intercourse.

- Uterine bleeding. Pain during or shortly after beginning or end of menstrual period; irregular periods, or abnormal uterine bleeding or spotting.

- Fullness, heaviness, pressure, swelling, or bloating in the abdomen. Some ovarian cysts become large enough to cause the lower abdomen to visibly swell.[2]

- When a cyst ruptures from the ovary, there may be sudden and sharp pain in the lower abdomen on one side.

- Large cysts can cause a change in frequency or ease of urination (such as inability to fully empty the bladder), or difficulty with bowel movements due to pressure on adjacent pelvic anatomy.[5]

- Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, headaches.

- Nausea or vomiting

- Weight gain

Other symptoms may depend on the cause of the cysts:[6]

- Symptoms that may occur if the cause of the cysts is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may include increased facial hair or body hair, acne, obesity and infertility.

- If the cause is endometriosis, then periods may be heavy, and intercourse painful.

The effect of cysts not related to PCOS on fertility is unclear.[7]

In other cases, the cyst is asymptomatic, and is discovered incidentally while doing medical imaging for another condition.[8] Ovarian cysts and other "incidentalomas" of the uterine adnexa appear in almost 5% of CT scans done on women.[8]

Complications[edit]

The most common complications are cyst rupture, which occasionally leads to internal bleeding ("hemorrhagic cyst"), and ovarian torsion.[5]

Cyst rupture[edit]

When the surface of cyst breaks, the contents can leak out; this is called a ruptured cyst. The main symptom is abdominal pain, which may last a few days to several weeks, but they can also be asymptomatic.[9]

A ruptured ovarian cyst is usually self-limiting, and only requires keeping an eye on the situation and pain medications for a few days, while the body heals itself.[5] Rupture of large ovarian cysts can cause bleeding inside the abdominal cavity.[5] Rarely, enough blood will be lost that the bleeding will produce hypovolemic shock, which can be a medical emergency requiring surgery.[5][10] However, normally, the internal bleeding is minimal and requires no intervention.[5]

Ovarian torsion[edit]

Ovarian torsion is a very painful medical condition requiring urgent surgery.[2] It can be caused by a pedunculated ovarian cyst that twisted in a way that cuts off the blood flow.[2] It is most likely to be seen in women of reproductive age, though it has happened in young girls (premenarche) and postmenopausal women.[11] Ovarian torsion may be more likely during pregnancy, especially during the third and fourth months of pregnancy, as the internal anatomy shifts to accommodate fetal growth.[5] Diagnosis relies on clinical examination and ultrasound imaging.[5]

Cysts larger than 4 cm are associated with approximately 17% risk.[citation needed]

Types[edit]

There are many types of ovarian cysts, some of which are normal and most of which are benign (non-cancerous).[2]

Functional[edit]

Functional cysts form as a normal part of the menstrual cycle. There are several types of functional cysts:

- Follicular cyst, the most common type of ovarian cyst.[2] In menstruating women, an ovarian follicle containing the ovum (an unfertilized egg) normally releases the ovum during ovulation.[2] If it does not release the ovum, a follicular cyst of more than 2.5 cm diameter may result.[6] A ruptured follicular cyst can is painful.[2]

- A luteal cyst is a cyst that forms after ovulation, from the corpus luteum (the remnant of the ovarian follicle, after the ovum has been released).[2] A luteal cyst is twice as likely to appear on the right side.[2] It normally resolves during the last week of the menstrual cycle.[2] A corpus luteum that is more than 3 cm is abnormal.[6][8]

- Theca lutein cysts occur within the thecal layer of cells surrounding developing oocytes. Under the influence of excessive hCG, thecal cells may proliferate and become cystic. This is usually on both ovaries.[6]

Non-functional[edit]

Non-functional cysts may include the following:

- An ovary with many cysts, which may be found in normal women, or within the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome

- Cysts caused by endometriosis, known as chocolate cysts

- Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst

- Dermoid cyst – the most common non-functional ovarian cyst, especially for women under the age of 30,[11] they are benign (non-cancerous) with varied morphology.[13] They can usually be diagnosed from ultrasound alone.[13] Depending on size, growth rate (usually slow), and the age of the woman, treatment might involve surgical removal or watchful waiting.[13] They are also called mature cystic teratomas.[11]

- Ovarian serous cystadenoma – more common in women between the age of 30 and 40.[11]

- Ovarian mucinous cystadenoma – although there is usually only one of these, they can grow very large, with diameters sometimes exceeding 50 cm (20 inches).[11]

- Paraovarian cyst

- Cystic adenofibroma

- Borderline tumoral cysts

-

Transvaginal ultrasonography of a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, probably originating from a corpus luteum cyst. The coagulating blood gives the content a cobweb-like appearance.

-

Transvaginal ultrasonography showing a 67 x 40 mm endometrioma, with a somewhat grainy content.

Risk factors[edit]

Risk factors include fertility status (more common in women of childbearing age) and irregular menstrual cycles.[14] Using combined hormonal contraception may reduce the risk, especially with high-dose pills,[14] but it does not treat existing cysts.[3]

Diagnosis[edit]

Ovarian cysts are usually diagnosed by pelvic ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, and correlated with clinical presentation and endocrinologic tests as appropriate.[15] Ultrasound is the most important imaging modality, as abnormalities seen in a CT scan sometimes prove to be normal in ultrasound.[5][8] If a different modality is needed, then MRIs are more reliable than CT scans.[5]

Ultrasound[edit]

Usually, an experienced sonographer can readily identify benign ovarian cysts, often with a level of accuracy that rivals other approaches.[5]

Follow-up imaging in women of reproductive age for incidentally discovered simple cysts on ultrasound is not needed until 5 cm, as these are usually normal ovarian follicles. Simple cysts 5 to 7 cm in premenopausal females should be followed yearly. Simple cysts larger than 7 cm require further imaging with MRI or surgical assessment. Because they are large, they cannot be reliably assessed by ultrasound alone; it can be difficult to see posterior wall soft tissue nodularity or thickened septation due to limited ultrasound beam penetrance at this size and depth. For the corpus luteum, a dominant ovulating follicle that typically appears as a cyst with circumferentially thickened walls and crenulated inner margins, follow up is not needed if the cyst is less than 3 cm in diameter.[8] In postmenopausal women, any simple cyst greater than 1 cm but less than 7 cm needs yearly follow-up, while those greater than 7 cm need MRI or surgical evaluation, similar to reproductive age females.[16]

For incidentally discovered dermoids, diagnosed on ultrasound by their pathognomonic echogenic fat, either surgical removal or yearly follow up is indicated, regardless of the woman's age. For peritoneal inclusion cysts, which have a crumpled tissue-paper appearance and tend to follow the contour of adjacent organs, follow up is based on clinical history. Hydrosalpinx, or fallopian tube dilation, can be mistaken for an ovarian cyst due to its anechoic appearance. Follow-up for this is also based on clinical presentation.[16]

For multilocular cysts with thin septation less than 3 mm, surgical evaluation is recommended. The presence of multiloculation suggests a neoplasm, although the thin septation implies that the neoplasm is benign. For any thickened septation, nodularity, vascular flow on color doppler, or growth over several ultrasounds, surgical removal may be considered due to concern of cancer.[16]

Scoring systems[edit]

Most ovarian cysts are not malignant; however, some do become cancerous.[2] There are several systems to assess risk of an ovarian cyst of being an ovarian cancer, including the RMI (risk of malignancy index), LR2 and SR (simple rules). Sensitivities and specificities of these systems are given in tables below:[17]

| Scoring systems | Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| RMI I | 44% | 95% | 79% | 90% |

| LR2 | 85% | 91% | 94% | 70% |

| SR | 93% | 83% | 93% | 76% |

Ovarian cysts may be classified according to whether they are a variant of the normal menstrual cycle, referred to as a functional or follicular cyst.[6]

Ovarian cysts are considered large when they are over 5 cm and giant when they are over 15 cm. In children, ovarian cysts reaching above the level of the umbilicus are considered giant.

Associated conditions[edit]

In juvenile hypothyroidism multicystic ovaries are present in about 75% of cases, while large ovarian cysts and elevated ovarian tumor marks are one of the symptoms of the Van Wyk and Grumbach syndrome.[18]

The CA-125 marker in children and adolescents can be frequently elevated even in absence of malignancy and conservative management should be considered.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome involves the development of multiple small cysts in both ovaries due to an elevated ratio of leutenizing hormone to follicle stimulating hormone, typically more than 25 cysts in each ovary, or an ovarian volume of greater than 10 mL.[19]

Larger bilateral cysts can develop as a result of fertility treatment due to elevated levels of HCG, as can be seen with the use of clomifene for follicular induction, in extreme cases resulting in a condition known as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.[20] Certain malignancies can mimic the effects of clomifene on the ovaries, also due to increased HCG, in particular gestational trophoblastic disease. Ovarian hyperstimulation occurs more often with invasive moles and choriocarcinoma than complete molar pregnancies.[21]

Risk of cancer[edit]

Accurately differentiating an cyst from a cancer is critical to management. Medical imaging showing a simple, smooth bubble of watery liquid is characteristic of a benign cyst.[8] If the cyst is large, is multilocular, or has complex internal features, such as papillary (bumpy) projections into the cyst or solid areas inside the cyst, it is more likely to be cancerous.[13]

A widely recognised method of estimating the risk of malignant ovarian cancer based on initial workup is the risk of malignancy index (RMI).[13][22] It is recommended that women with an RMI score over 200 should be referred to a centre with experience in ovarian cancer surgery.[23]

The RMI is calculated as follows:[23]

- RMI = ultrasound score × menopausal score × CA-125 level in U/ml.

There are two methods to determine the ultrasound score and menopausal score, with the resultant RMI being called RMI 1 and RMI 2, respectively, depending on what method is used:[23]

| Feature | RMI 1 | RMI 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

Ultrasound abnormalities:

|

|

|

| Menopausal score |

|

|

| CA-125 | Quantity in U/ml | Quantity in U/ml |

RMI 2 is regarded as more sensitive than RMI 1,[23] but the model has low specificity, which means that many of the suspected cancers turn out to be overdiagnosed benign cysts.[13] The calculation is often inaccurate during pregnancy, especially when CA-125 levels peak towards the end of the first trimester.[5]

The International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) group has produced a different model. Theirs relies on "simple descriptors" and "simple rules".[5] An example of a simple descriptor for a benign cyst is "Unilocular cyst of anechoic content with regular walls and largest diameter less than 10 cm".[5] An example of a simple rule is acoustic shadows are associated with benign cysts.[5]

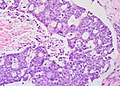

Histopathology[edit]

In case an ovarian cyst is surgically removed, a more definite diagnosis can be made by histopathology:

| Type | Subtype | Typical microscopy findings | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional cyst | Follicular cyst |

|

|

| Corpus luteum cyst |

|

| |

| Cystadenoma | Serous cystadenoma | Cyst lining consisting of a simple epithelium, whose cells may be either:[26]

|

|

| Mucinous cystadenoma | Lined by a mucinous epithelium |

| |

| Dermoid cyst | Well-differentiated components from at least two, and usually three,[11] germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and/or endoderm).[27] |

| |

| Endometriosis | At least two of the following three criteria:[28]

|

| |

| Borderline tumor | Atypical epithelial proliferation without stromal invasion.[29] |

| |

| Ovarian cancer | Many different types, but generally severe dysplasia/atypia and invasion. |

| |

| Simple squamous cyst | Simple squamous epithelium and not conforming to diagnoses above (a diagnosis of exclusion) |

| |

Treatment[edit]

In general, there are three options for dealing with an ovarian cyst:

- watchful waiting (e.g., waiting to see whether symptoms resolve on their own),[8]

- additional imaging or investigation (e.g., getting an ultrasound later to see whether the cyst is growing),[8] and

- surgery (e.g., surgical removal of the cyst).[8]

Cysts associated with hypothyroidism or other endocrine problems are managed by treating the underlying condition.

About 95% of ovarian cysts are benign (not cancerous).[30] Functional cysts and hemorrhagic ovarian cysts usually resolve spontaneously within one or two menstrual cycles.[11]

However, the bigger an ovarian cyst is, the less likely it is to disappear on its own.[31] Treatment may be required if cysts persist over several months, grow, or cause increasing pain.[32] Cysts that persist beyond two or three menstrual cycles, or occur in post-menopausal women, may indicate more serious disease and should be investigated through ultrasonography and laparoscopy, especially in cases where family members have had ovarian cancer. Such cysts may require surgical biopsy. Additionally, a blood test may be taken before surgery to check for elevated CA-125, a tumour marker, which is often found in increased levels in ovarian cancer, although it can also be elevated by other conditions resulting in a large number of false positives.[33]

Expectant management[edit]

If the cyst is asymptomatic and appears to be either benign or normal (i.e., a cyst with a benign appearance and a size of less than 3 cm diameter in premenopausal women or less than 1 cm in postmenopausal women[8]), then delaying surgery, in the hope that it will prove unnecessary, is appropriate and recommended.[8] Normal ovarian cysts require neither treatment nor additional investigations.[8] Benign but medium-size cysts may prompt an additional pelvic ultrasound after a couple of months.[8] (The larger the cyst, the sooner the follow-up imaging is done.[8])

Symptom management [edit]

Pain associated with ovarian cysts may be treated in several ways:

- Pain relievers such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,[1] or opioids.

- While hormonal birth control prevents the development of new cysts in those who frequently get them,[1] it is not useful for the treatment of current cysts.[3]

Surgery[edit]

Although most cases of ovarian cysts are monitored and stabilize or resolve without surgery, some cases require surgery.[34] Common indications for surgical management include ovarian torsion, ruptured cyst, concerns that the cyst is cancerous, and pain;[11] some surgeons additionally recommend removing all large cysts.[11]

The surgery may involve removing the cyst alone, or one or both ovaries.[11] Very large, potentially cancerous, and recurrent cysts, particularly in menopausal women, are more likely to be treated by removing the affected ovary, or both the ovary and its Fallopian tube (salpingo-oophorectomy).[11] Except in extreme cases, fertility can normally be preserved.[11]

Simple benign cysts can be drained through fine-needle aspiration.[5] However, the risk of recurrence is fairly high (33–40%), and if a cancerous tumor was misdiagnosed, it could cause the cancer to spread.[5]

The surgical technique is typically a minimally invasive or laparoscopic approach performed under general anaesthesia,[11] unless the cyst is particularly large (e.g., 10 cm [4 inches] in diameter), or if pre-operative imaging, such as pelvic ultrasound, suggests malignancy or complex anatomy.[13] For large cysts, open laparotomy or a mini-laparotomy (a smaller incision through the abdominal wall) may be preferred.[13] Minimally invasive surgeries are not used when ovarian cancer is suspected.[13][11] Additionally, if the pelvic surgery is being done, some women choose to have prophylactic salpingectomy done at the same time, to reduce their future risk of cancer.[11]

If the cyst ruptures during surgery, the contents may irritate the peritoneum and cause internal adhesions.[11] The cyst may be drained before removal, and the abdominal cavity carefully irrigated to remove any leaked fluids, to reduce this risk.[11]

Frequency[edit]

Most women of reproductive age develop small cysts each month. Simple, smooth ovarian cysts, smaller than 3 cm and apparently filled with water, are considered normal.[8] Large cysts that cause problems occur in about 8% of women before menopause.[1] Ovarian cysts are present in about 16% of women after menopause, and have a higher risk of being cancer than in younger women.[1][4] If a cyst appears benign during diagnosis, then it has a less than 1% chance of being either cancer or borderline malignant.[11]

Benign ovarian cysts are common in asymptomatic premenarchal girls and found in approximately 68% of ovaries of girls 2–12 years old and in 84% of ovaries of girls 0–2 years old. Most of them are smaller than 9 mm while about 10–20% are larger macrocysts. While the smaller cysts mostly disappear within 6 months the larger ones appear to be more persistent.[35][36]

In pregnancy[edit]

Ovarian cysts are seen during pregnancy.[14][5] They tend to be simple benign cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter, most commonly functional follicular or luteal cysts.[14] They are more common earlier in the pregnancy.[5] When they are detected early in pregnancy, such as during a routine prenatal ultrasound, they usually resolve on their own after a couple of months.[14][5] Pregnancy changes hormone levels, and that can affect the diagnostic process.[5] For example, some endometriomas (a type of benign ovarian cyst) will undergo decidualization, which can make them look more like a cancerous tumor in medical imaging.[5]

A large cyst, if it puts pressure on the lower part of the uterus, can cause obstructed labor (also called labor dystocia).[5]

Rarely, a cyst discovered during pregnancy will prove to be cancerous or to have cancerous potential.[5] Malignant tumors discovered during pregnancy are usually germ cell, sex cord–gonadal stromal, or carcinomas, or slightly less commonly, borderline serous or mucinous cysts.[5]

History[edit]

In 1809, Ephraim McDowell became the first surgeon to successfully remove an ovarian cyst.[37]

Society and culture[edit]

Benign tumors were known in ancient Egypt, and an ovarian cyst has been identified in a mummy, Irtyersenu (c. 600 BC), that was autopsied in the early 19th century.[38]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Ovarian cysts". Office on Women's Health. April 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Law, Jonathan; Martin, Elizabeth A., eds. (2020). "ovarian cyst". Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford Quick Reference (10th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-883661-2.

- ^ a b c Grimes, David A; Jones, LaShawn B.; Lopez, Laureen M; Schulz, Kenneth F (29 April 2014). "Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006134. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006134.pub5. PMC 10964840. PMID 24782304.

- ^ a b Mimoun, C.; Fritel, X.; Fauconnier, A.; Deffieux, X.; Dumont, A.; Huchon, C. (December 2013). "Épidémiologie des tumeurs ovariennes présumées bénignes" [Epidemiology of presumed benign ovarian tumors]. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction (in French). 42 (8): 722–729. doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2013.09.027. PMID 24210235.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Zvi, Masha Ben; Thanatsis, Nikolaos; Vashisht, Arvind (2023-07-31), Jha, Swati; Madhuvrata, Priya (eds.), "Ovarian Cysts in Pregnancy", Gynaecology for the Obstetrician (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–13, doi:10.1017/9781009208802.003, ISBN 978-1-009-20880-2

- ^ a b c d e f Ovarian Cysts at eMedicine

- ^ Legendre, Guillaume; Catala, Laurent; Morinière, Catherine; Lacoeuille, Céline; Boussion, Françoise; Sentilhes, Loïc; Descamps, Philippe (March 2014). "Relationship between ovarian cysts and infertility: what surgery and when?". Fertility and Sterility. 101 (3): 608–614. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.021. PMID 24559614.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tsili, A. C.; Argyropoulou, M. I. (2020-11-16). "Adnexal incidentalomas on multidetector CT: how to manage and characterise". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 40 (8): 1056–1063. doi:10.1080/01443615.2019.1676214. ISSN 0144-3615.

- ^ Ovarian Cyst Rupture at eMedicine

- ^ "Ovarian cysts". womenshealth.gov. 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mettler, Liselotte; Alkatout, Ibrahim (2020-03-23), Saridoğan, Ertan; Kilic, Gokhan Sami; Ertan, Kubilay (eds.), "12. Management of Benign Adnexal Masses", Minimally Invasive Surgery in Gynecological Practice, De Gruyter, pp. 127–133, doi:10.1515/9783110535204-012, ISBN 978-3-11-053520-4

- ^ Abduljabbar, Hassan S.; Bukhari, Yasir A.; Hachim, Estabrq G. Al; Ashour, Ghazal S.; Amer, Afnan A.; Shaikhoon, Mohammed M.; Khojah, Mohammed I. (July 2015). "Review of 244 cases of ovarian cysts". Saudi Medical Journal. 36 (7): 834–838. doi:10.15537/smj.2015.7.11690. PMC 4503903. PMID 26108588.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bean, Elisabeth; Jurkovic, Davor (2020-03-23), Saridoğan, Ertan; Kilic, Gokhan Sami; Ertan, Kubilay (eds.), "2. Preoperative imaging for minimally invasive surgery in gynecology", Minimally Invasive Surgery in Gynecological Practice, De Gruyter, pp. 17–27, doi:10.1515/9783110535204-002, ISBN 978-3-11-053520-4

- ^ a b c d e Bitzer, Johannes (2022-04-07), Bitzer, Johannes; Mahmood, Tahir A. (eds.), "Benign Breast Disease, and Benign Uterine and Ovarian Conditions", Handbook of Contraception and Sexual Reproductive Healthcare (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 110–115, doi:10.1017/9781108961110.018, ISBN 978-1-108-96111-0

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Ovarian cysts

- ^ a b c Levine, Deborah; Brown, Douglas L.; Andreotti, Rochelle F.; Benacerraf, Beryl; Benson, Carol B.; Brewster, Wendy R; Coleman, Beverly; DePriest, Paul; Doubilet, Peter M.; Goldstein, Steven R.; Hamper, Ulrike M.; Hecht, Jonathan L.; Horrow, Mindy; Hur, Hye-Chun; Marnach, Mary; Patel, Maitray D.; Platt, Lawrence D.; Puscheck, Elizabeth; Smith-Bindman, Rebecca (September 2010). "Management of Asymptomatic Ovarian and Other Adnexal Cysts Imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement". Radiology. 256 (3): 943–954. doi:10.1148/radiol.10100213. PMC 6939954. PMID 20505067. S2CID 10270209.

- ^ Kaijser, Jeroen; Sayasneh, Ahmad; Van Hoorde, Kirsten; Ghaem-Maghami, Sadaf; Bourne, Tom; Timmerman, Dirk; Van Calster, Ben (1 May 2014). "Presurgical diagnosis of adnexal tumours using mathematical models and scoring systems: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (3): 449–462. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt059. PMID 24327552.

- ^ Durbin, Kaci L.; Diaz-Montes, Teresa; Loveless, Meredith B. (August 2011). "Van Wyk and Grumbach Syndrome: An Unusual Case and Review of the Literature". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 24 (4): e93–e96. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2010.08.003. PMID 21600802.

- ^ Dewailly, D.; Lujan, M. E.; Carmina, E.; Cedars, M. I.; Laven, J.; Norman, R. J.; Escobar-Morreale, H. F. (1 May 2014). "Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: a task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (3): 334–352. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt061. PMID 24345633.

- ^ Altinkaya, Sunduz Ozlem; Talas, Betul Bayir; Gungor, Tayfun; Gulerman, Cavidan (October 2009). "Treatment of clomiphene citrate-related ovarian cysts in a prospective randomized study. A single center experience". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 35 (5): 940–945. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01041.x. PMID 20149045. S2CID 36836406.

- ^ Suzuki, Hirotada; Matsubara, Shigeki; Uchida, Shin-ichiro; Ohkuchi, Akihide (October 2014). "Ovary hyperstimulation syndrome accompanying molar pregnancy: case report and review of the literature". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 290 (4): 803–806. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3319-0. PMID 24966119. S2CID 27120087.

- ^ NICE clinical guidelines Issued: April 2011. Guideline CG122. Ovarian cancer: The recognition and initial management of ovarian cancer Archived 2013-09-22 at the Wayback Machine, Appendix D: Risk of malignancy index (RMI I).

- ^ a b c d Network, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines (2003). "EPITHELIAL OVARIAN CANCER SECTION 3: DIAGNOSIS". Epithelial ovarian cancer : a national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN. ISBN 978-1899893935. Archived from the original on 2013-09-22.

- ^ a b Mohiedean Ghofrani. "Ovary - nontumor - Nonneoplastic cysts / other - Follicular cysts". Pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 August 2011. Revised: 5 March 2020

- ^ a b c Aurelia Busca, Carlos Parra-Herran. "Ovary - nontumor - Nonneoplastic cysts / other - Corpus luteum cyst (CLC)". Pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 November 2016. Revised: 5 March 2020

- ^ Shahrzad Ehdaivand, M.D. "Ovary tumor - serous tumors - Serous cystadenoma / adenofibroma / surface papilloma". Pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 June 2012. Revised: 5 March 2020

- ^ Sahin, Hilal; Abdullazade, Samir; Sanci, Muzaffer (April 2017). "Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a cutting edge overview on imaging features". Insights into Imaging. 8 (2): 227–241. doi:10.1007/s13244-016-0539-9. PMC 5359144. PMID 28105559.

- ^ Aurelia Busca, Carlos Parra-Herran. "Ovary - nontumor - Nonneoplastic cysts / other - Endometriosis". Pathology Outlines. Topic Completed: 1 August 2017. Revised: 5 March 2020

- ^ Lee-may Chen, MDJonathan S Berek, MD, MMS. "Borderline ovarian tumors". UpToDate.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This topic last updated: Feb 08, 2019. - ^ "Symptoms of ovarian cysts". 2017-10-23. Archived from the original on 2009-05-12. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Edward I. Bluth (2000). Ultrasound: A Practical Approach to Clinical Problems. Thieme. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-86577-861-0. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12.

- ^ Susan A. Orshan (2008). Maternity, Newborn, and Women's Health Nursing: Comprehensive Care Across the Lifespan. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 161. ISBN 978-0-7817-4254-2.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: CA-125

- ^ Tamparo, Carol; Lewis, Marcia (2011). Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: Library of Congress. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- ^ Cohen, H L; Eisenberg, P; Mandel, F; Haller, J O (July 1992). "Ovarian cysts are common in premenarchal girls: a sonographic study of 101 children 2-12 years old". American Journal of Roentgenology. 159 (1): 89–91. doi:10.2214/ajr.159.1.1609728. PMID 1609728.

- ^ Qublan HS, Abdel-hadi J (2000). "Simple ovarian cysts: Frequency and outcome in girls aged 2-9 years". Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. 27 (1): 51–3. PMID 10758801.

- ^ Warner, John Harley (2014). "Medicine: From 1776 to the 1870s". In Slotten, Hugh Richard (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the History of American Science, Medicine, and Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976666-6.

- ^ Redford, Donald B., ed. (2001). "Disease". The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

Benign tumors include...the cystadenoma of the ovary in the Granville mummy (Irty-senu), now in the British Museum...

Further reading[edit]

- McBee, W. C; Escobar, P. F; Falcone, T. (1 February 2007). "Which ovarian masses need intervention?". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 74 (2): 149–157. doi:10.3949/ccjm.74.2.149. PMID 17333642. S2CID 45443236.

- Simcock, B; Anderson, N (February 2005). "Diagnosis and management of simple ovarian cysts: An audit". Australasian Radiology. 49 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01389.x. PMID 15727606.

- Ross, Elisa K.; Kebria, Medhi (August 2013). "Incidental ovarian cysts: When to reassure, when to reassess, when to refer". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 80 (8): 503–514. doi:10.3949/ccjm.80a.12155. PMID 23908107. S2CID 28081941.

- "Ovarian cyst - Treatment". National Health Service. 3 October 2018.

- Gerber, B.; Müller, H.; Külz, T.; Krause, A.; Reimer, T. (1 April 1997). "Simple ovarian cysts in premenopausal patients". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 57 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(97)02832-4. PMID 9175670. S2CID 34289061.

- Potter, Andrew W.; Chandrasekhar, Chitra A. (October 2008). "US and CT Evaluation of Acute Pelvic Pain of Gynecologic Origin in Nonpregnant Premenopausal Patients". RadioGraphics. 28 (6): 1645–1659. doi:10.1148/rg.286085504. PMID 18936027.

- Crespigny, Lachlan Ch.; Robinson, Hugh P.; Davoren, Ruth A. M.; Fortune, Denys (September 1989). "The 'simple' ovarian cyst: aspirate or operate?". BJOG. 96 (9): 1035–1039. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb03377.x. PMID 2679871. S2CID 22501317.