Tuned mass damper

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (March 2020) |

A tuned mass damper (TMD), also known as a harmonic absorber or seismic damper, is a device mounted in structures to reduce mechanical vibrations, consisting of a mass mounted on one or more damped springs. Its oscillation frequency is tuned to be similar to the resonant frequency of the object it is mounted to, and reduces the object's maximum amplitude while weighing much less than it.

TMDs can prevent discomfort, damage, or outright structural failure. They are frequently used in power transmission, automobiles and buildings.

Principle

[edit]

Tuned mass dampers stabilize against violent motion caused by harmonic vibration. They use a comparatively lightweight component to reduce the vibration of a system so that its worst-case vibrations are less intense. Roughly speaking, practical systems are tuned to either move the main mode away from a troubling excitation frequency, or to add damping to a resonance that is difficult or expensive to damp directly. An example of the latter is a crankshaft torsional damper. Mass dampers are frequently implemented with a frictional or hydraulic component that turns mechanical kinetic energy into heat, like an automotive shock absorber.

Given a motor with mass m1 attached via motor mounts to the ground, the motor vibrates as it operates and the soft motor mounts act as a parallel spring and damper, k1 and c1. The force on the motor mounts is F0. In order to reduce the maximum force on the motor mounts as the motor operates over a range of speeds, a smaller mass, m2, is connected to m1 by a spring and a damper, k2 and c2. F1 is the effective force on the motor due to its operation.

The graph shows the effect of a tuned mass damper on a simple spring–mass–damper system, excited by vibrations with an amplitude of one unit of force applied to the main mass, m1. An important measure of performance is the ratio of the force on the motor mounts to the force vibrating the motor, F0/F1. This assumes that the system is linear, so if the force on the motor were to double, so would the force on the motor mounts. The blue line represents the baseline system, with a maximum response of 9 units of force at around 9 units of frequency. The red line shows the effect of adding a tuned mass of 10% of the baseline mass. It has a maximum response of 5.5, at a frequency of 7. As a side effect, it also has a second normal mode and will vibrate somewhat more than the baseline system at frequencies below about 6 and above about 10.

The heights of the two peaks can be adjusted by changing the stiffness of the spring in the tuned mass damper. Changing the damping also changes the height of the peaks, in a complex fashion. The split between the two peaks can be changed by altering the mass of the damper (m2).

The Bode plot is more complex, showing the phase and magnitude of the motion of each mass, for the two cases, relative to F1.

In the plots at right, the black line shows the baseline response (m2 = 0). Now considering m2 = m1/10, the blue line shows the motion of the damping mass and the red line shows the motion of the primary mass. The amplitude plot shows that at low frequencies, the damping mass resonates much more than the primary mass. The phase plot shows that at low frequencies, the two masses are in phase. As the frequency increases m2 moves out of phase with m1 until at around 9.5 Hz it is 180° out of phase with m1, maximizing the damping effect by maximizing the amplitude of x2 − x1, this maximizes the energy dissipated into c2 and simultaneously pulls on the primary mass in the same direction as the motor mounts.

Mass dampers in automobiles

[edit]Motorsport

[edit]The tuned mass damper was introduced as part of the suspension system by Renault on its 2005 F1 car (the Renault R25), at the 2005 Brazilian Grand Prix. The system reportedly reduced lap times by 0.3 seconds: a phenomenal gain for a relatively simple device.[1] The stewards of the meeting deemed it legal, but the FIA appealed against that decision.

Two weeks later, the FIA International Court of Appeal deemed the mass damper illegal.[2][3] It was deemed to be illegal because the mass was not rigidly attached to the chassis; the influence the damper had on the pitch attitude of the car in turn affected the gap under the car and the ground effects of the car. As such, the damper was considered to be a movable aerodynamic device and hence an illegal influence on the performance of the aerodynamics.

Production cars

[edit]Tuned mass dampers are widely used in production cars, typically on the crankshaft pulley to control torsional vibration and, more rarely, the bending modes of the crankshaft. They are also used on the driveline for gearwhine, and elsewhere for other noises or vibrations on the exhaust, body, suspension or anywhere else. Almost all modern cars will have one mass damper, and some may have ten or more.

The usual design of damper on the crankshaft consists of a thin band of rubber between the hub of the pulley and the outer rim. This device, often called a harmonic damper, is located on the other end of the crankshaft opposite of where the flywheel and the transmission are. An alternative design is the centrifugal pendulum absorber which is used to reduce the internal combustion engine's torsional vibrations.

All four wheels of the Citroën 2CV incorporated a tuned mass damper (referred to as a "Batteur" in the original French) of very similar design to that used in the Renault F1 car, from the start of production in 1949 on all four wheels, before being removed from the rear and eventually the front wheels in the mid 1970s.

Mass dampers in bridges

[edit]

The tuned mass damper is widely being used as a method to add damping to bridges. One use-case for tuned mass dampers in bridges is to prevent large vibrations due to resonance with pedestrian loads.[5] By adding a tuned mass damper, damping is added to the structure which causes the vibration of the structure to be reduced as the vibration steady state amplitude is inversely proportional to the damping of the structure.[6]

Mass dampers in spacecraft

[edit]One proposal to reduce vibration on NASA's Ares solid fuel booster was to use 16 tuned mass dampers as part of a design strategy to reduce peak loads from 6g to 0.25g, with the TMDs being responsible for the reduction from 1g to 0.25g, the rest being done by conventional vibration isolators between the upper stages and the booster.[7][8]

Dampers in power transmission lines

[edit]

High-tension lines often have small barbell-shaped Stockbridge dampers hanging from the wires to reduce the high-frequency, low-amplitude oscillation termed flutter.[9][10]

Dampers in wind turbines

[edit]A standard tuned mass damper for wind turbines consists of an auxiliary mass which is attached to the main structure by means of springs and dashpot elements. The natural frequency of the tuned mass damper is basically defined by its spring constant and the damping ratio determined by the dashpot. The tuned parameter of the tuned mass damper enables the auxiliary mass to oscillate with a phase shift with respect to the motion of the structure. In a typical configuration, an auxiliary mass hung below the nacelle of a wind turbine supported by dampers or friction plates.[citation needed]

Dampers in buildings and related structures

[edit]

When installed in buildings, dampers are typically huge concrete blocks or steel bodies mounted in skyscrapers or other structures, which move in opposition to the resonance frequency oscillations of the structure by means of springs, fluid, or pendulums.

Sources of vibration and resonance

[edit]Unwanted vibration may be caused by environmental forces acting on a structure, such as wind or earthquake, or by a seemingly innocuous vibration source causing resonance that may be destructive, unpleasant or simply inconvenient.

Earthquakes

[edit]The seismic waves caused by an earthquake will make buildings sway and oscillate in various ways depending on the frequency and direction of ground motion, and the height and construction of the building. Seismic activity can cause excessive oscillations of the building which may lead to structural failure. To enhance the building's seismic performance, a proper building design is performed engaging various seismic vibration control technologies. As mentioned above, damping devices had been used in the aeronautics and automobile industries long before they were standard in mitigating seismic damage to buildings. In fact, the first specialized damping devices for earthquakes were not developed until late in 1950.[11]

Mechanical human sources

[edit]

Masses of people walking up and down stairs at once, or great numbers of people stomping in unison, can cause serious problems in large structures like stadiums if those structures lack damping measures.

Wind

[edit]The force of wind against tall buildings can cause the top of skyscrapers to move more than a meter. This motion can be in the form of swaying or twisting, and can cause the upper floors of such buildings to move. Certain angles of wind and aerodynamic properties of a building can accentuate the movement and cause motion sickness in people. A TMD is usually tuned to its building's resonant frequency to work efficiently. However, during their lifetimes, high-rise and slender buildings may experience natural resonant frequency changes under wind speed, ambient temperature and relative humidity variations, among other factors, which requires a robust TMD design.

Examples of buildings and structures with tuned mass dampers

[edit]- Australia

- Sydney Tower in Sydney, Australia - has a water tank used to dampen oscillations from high winds and potentially from earthquakes. "Engineering and Construction of the Sydney Tower".

- Brazil

- Canada

- One Wall Centre in Vancouver — employs tuned liquid column dampers, a unique form of tuned mass damper at the time of their installation.

- CN Tower in Toronto.

- China

- Shanghai Tower in Shanghai, China, is the third tallest building in the world.

- Shanghai World Financial Center in Shanghai, China

- Czech republic

- Ještěd Tower (1973)[12]

- Taiwan

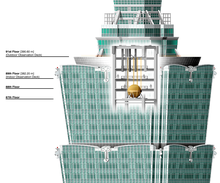

- Taipei 101 skyscraper — 660 metric tons (730 short tons) damper, formerly the world's heaviest.[13] Located on 87th to 92nd floors.

- Germany

- Berlin Television Tower (Fernsehturm) — tuned mass damper located in the spire.

- VLF transmitter DHO38 – cylindrical containers filled with granulate in the mast structure

- India

- ATC Tower Delhi Airport in New Delhi, India — a 50-ton tuned mass damper installed just beneath the ATC floor at 90m.

- Statue of Unity in Gujarat, India – two tuned mass dampers of 250 ton each located at the chest level of Sardar Patel statue.[14][15]

- Iran

- Ireland

- Dublin Spire in Dublin, Ireland — designed with a tuned mass damper to ensure aerodynamic stability during a wind storm .

- Japan

- Akashi Kaikyō Bridge, between Honshu and Shikoku in Japan, formerly the world's longest suspension bridge, uses pendulums within its suspension towers as tuned mass dampers.

- Ribbon Chapel[16] in Hiroshima, Japan, uses a TMD to damp vibrations in two intertwined helical stairways.[17]

- Tokyo Skytree

- Yokohama Landmark Tower[18]

- Chiba Port Tower, Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Almaty Tower

- "Kazakh Eli" monument at Independence Square, Nur-Sultan

- Russia

- Victory Monument at Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow

- Olympic torch at Sochi Olympic Park,

- Steel chimneys in Moscow (Thermal Power Plant 27), Ryazan Power Station, Sochi Thermal Power Plant etc.

- Sakhalin-I — An offshore drilling platform

- United Arab Emirates

- Burj al-Arab in Dubai — 11 tuned mass dampers.

- United Kingdom

- London Millennium Bridge — nicknamed 'The Wobbly Bridge' due to swaying under heavy foot traffic. Dampers were fitted in response.

- One Canada Square — Prior to the topping out of the Shard in 2012, this was the tallest building in the UK.

- United States

- 111 West 57th Street in New York City — Contains the heaviest solid damper in the world, at 800 short tons (730 t).[19]

- 432 Park Avenue in New York City[20]

- Bally's-to-Bellagio, Bally's-to-Caesars Palace, and Treasure Island-to-The Venetian Pedestrian Bridges in Las Vegas

- Bloomberg Tower/731 Lexington in New York City

- Citigroup Center in New York City — Designed by William LeMessurier and completed in 1977, it was one of the first skyscrapers to use a tuned mass damper to reduce sway.[21] Uses a concrete version.

- Comcast Center in Philadelphia — Contains the largest Tuned Liquid Column Damper (TLCD) in the world at 1,300 short tons (1,200 t).[22]

- Comcast Technology Center in Philadelphia — A set of five tuned dampers containing 125,000 gallons of water—about 500 tons—are located on the 57th floor between the hotel's rooms and lobby.[23]

- Grand Canyon Skywalk, Arizona

- John Hancock Tower in Boston (1976) — The first building to use a tuned mass damper, which was added after the building was completed.

- One Madison in New York City[24]

- One Rincon Hill South Tower, San Francisco — First building in California to have a liquid tuned mass damper

- Park Tower in Chicago — The first building in the United States to be designed with a tuned mass damper from the outset.

- Random House Tower — Uses two liquid filled dampers in New York City

- Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport Los Angeles

- Trump World Tower in New York City

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "How Renault Won a World Championship by Creating a Tuned Mass Damper". Moregoodink.com. Retrieved 2019-02-08.

- ^ Bishop, Matt (2006). "The Long Interview: Flavio Briatore". F1 Racing (October): 66–76.

- ^ "FIA bans controversial damper system". Pitpass.com. 21 July 2006. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Jan Linzelviaduct – Tuned Mass Damper". Flow engineering. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ^ Heinemeyer, Cristoph; Butz, Christiane; Keil, Andreas; Schlaich, Mike; Goldbeck, Arndt; Trometor, Stefan; Lukic, Mladen; Chabrolin, Bruno; Lemaire, Armand (2009-10-01). "Design of Lightweight Footbridges for Human Induced Vibrations". JRC Publications Repository. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ^ Akkas, Kaan; Bayindir, Cihan (2023-10-13). "Efficient measurement of floating breakwater vibration and controlled vibration parameters using compressive sensing". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part M: Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment. 238 (2): 318–324. doi:10.1177/14750902231203777. S2CID 264110144. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ^ "Ares I Thrust Oscillation meetings conclude with encouraging data, changes". NASASpaceFlight.com. 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ "Shock Absorber Plan Set for NASA's New Rocket". SPACE.com. 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Sauter, D; Hagedorn, P (December 2002). "On the hysteresis of wire cables in Stockbridge dampers". International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics. 37 (8): 1453–1459. Bibcode:2002IJNLM..37.1453S. doi:10.1016/S0020-7462(02)00028-8. INIST 13772262.

- ^ "Cable clingers – 27 October 2007". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Reitherman, Robert (2012). Earthquakes and Engineers: An International History. Reston, VA: ASCE Press. ISBN 9780784410714. Archived from the original on 2012-07-26.

- ^ Sial. Švácha, Rostislav., Beran, Lukáš, 1978-, Muzeum umění Olomouc., SIAL architekti a inženýři (Firm) (1st ed.). Olomouc: Arbor vitae. 2010. pp. 50–61. ISBN 9788087164419. OCLC 677863682.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ taipei-101.com.tw

- ^ "India Unveils 'Statue of Unity' - The Worlds Largest Statue". Born to Engineer. 2018-11-02. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

Two 250 tonne tuned mass dampers were placed at chest height to control the sway in high winds.

- ^ "The Statue of Unity | Sardar Patel | L&T". 2019-03-23. Archived from the original on 2019-03-23. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

To arrest any sway of such a tall structure, two Tuned Mass Dampers of 250 tonnes each have been used.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ ACS, Matthew Allard (November 24, 2015). "RIBBON CHAPEL" – via Vimeo.

- ^ Nakamura, Hiroshi (4 February 2015). "Ribbon Chapel / Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP Architects". ArchDaily. Retrieved 2017-02-15.

- ^ Luca, Septimiu-George; Pastia, Cristian; Chira, Florentina (2007). "Recent Applications of Some Active Control Systems to Civil Engineering Structures". The Bulletin of the Polytechnic Institute of Jassy, Construction. Architecture Section. 53 (1–2): 21–28.

- ^ "Tapering Begins as 111 West 57th Street Reaches for 1,428-Foot Pinnacle". 18 April 2018.

- ^ Stewart, Aaron. "In Detail> 432 Park Avenue". The Architect's Newspaper. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Petroski, Henry (1996). Invention by Design: How Engineers Get from Thought to Thing. Harvard University Press. pp. 205–208. ISBN 9780674463677.

- ^ "Comcast Center" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2012. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Bob Fernandez (December 10, 2014). "Engineers on the rise: Four young professionals tackle a career-making project". philly.com. Philadelphia Media Network (Digital), LLC. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ Staff (August 2011) "One Madison Park, New York City" Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat website. Archived 28 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine.