Ocean Shores, Washington

Ocean Shores | |

|---|---|

Ocean Shores main entrance | |

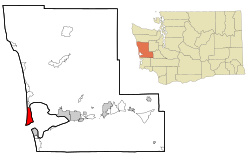

Location of Ocean Shores, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°58′18″N 124°9′17″W / 46.97167°N 124.15472°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Grays Harbor |

| Founded | 1970 |

| Incorporated | November 3, 1970 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Frank Eluden[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.78 sq mi (35.68 km2) |

| • Land | 8.52 sq mi (22.06 km2) |

| • Water | 5.26 sq mi (13.62 km2) |

| Elevation | 23 ft (7 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 6,715 |

| • Estimate (2022)[4] | 7,344 |

| • Density | 762.30/sq mi (294.32/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98569 |

| Area code | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-50570 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1510681[5] |

| Website | osgov.com |

Ocean Shores is a city in Grays Harbor County, Washington, United States. The population was 6,715 at the 2020 census.[3]

History[edit]

The City of Ocean Shores occupies the Point Brown peninsula on the Washington coast. Long before the arrival of European explorers and settlers, the peninsula was used by the various local tribes for trading and other purposes. The Chinook, Chehalis, and Quinault tribes used the area, as well as others that now make up the Quinault Indian Nation.

On May 7, 1792, Captain Robert Gray sailed into the bay and named the area Bullfinch Harbor. Later, Captain George Vancouver renamed the area Grays Harbor after Captain Gray. The first established white settler on the Point was Matthew McGee, who settled in the early 1860s. He sold the southern portion of the peninsula to A.O. Damon in 1878 for a trading supply center whose dock extended into the Oyehut channel. A.O. Damon took over the entire peninsula from McGee, and the land was passed along to his grandson, Ralph Minard, who used the area as a cattle ranch from 1929 until he sold to the Ocean Shores Development Corporation in 1960 for $1,000,000.

At the time the Washington State legislature was considering legalizing some forms of gambling. In expectation of a huge casino development, the Ocean Shores Development Corporation opened their sale of lots in a travel trailer parked in the dunes. Soon the word spread about the California-style development of the place called Ocean Shores. Lots began at $595 and were sold sight unseen from the first plat maps. As the numbers of lots sold rose, the prices rose. Property lots were staked and numbered only as the road construction crews began to lay out the massive road system. Even though the first roads were only 20 miles (32 km) in length, the downtown area had mercury vapor lights to show that this was a booming city. In the first year 25 homes were constructed and their owners had charter membership certificates in the Ocean Shores Community Club.

As the development grew, the Ginny Simms Restaurant and Nightclub brought in the Hollywood set. In fact, on its opening night, chartered planes flew up a whole contingent of Hollywood stars, and 11,000 people turned out at Bowerman Basin to see the celebrities.

By December 1960, 25 miles (40 km) of canals were planned, a six-hole golf course was drawing players, and the mall shopping area was ready for the 1961 Ocean Shores Estates construction boom. The mall, 100 motel units, three restaurants and an airstrip sprang up from the sandy ground, with the marina opening in 1963. The SS Catala was brought up from California to become a "boatel" and charter fleet office. Two years later a southwest winter storm drove her into the sand and for many years she was the most famous shipwreck on the Washington Coast. In 1966 the gates to the city were installed.

Pat Boone became a local resident in 1967 as a stockholder in Ocean Shores Estates Incorporated, and promotion of the development was sped along by the Celebrity Golf tournaments hosted by Boone.[6]

By 1969, Ocean Shores was declared the "richest little city" per capita in the country,[7] with an assessed valuation of $35 million and 900 permanent residents. The following year the city was incorporated and a planning commission was formed to zone the city and codify streets. The city's first school opened in 1971 and road paving began in earnest.

During the 1970s, the town struggled through many setbacks brought on mainly by the state's economic recession. By the 1980s, the slump was over and construction of homes and businesses accelerated again.

Geography[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.40 square miles (32.12 km2), of which 8.51 square miles (22.04 km2) is land and 3.89 square miles (10.08 km2) is water.[8]

Climate[edit]

Ocean Shores experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), with tendencies towards a Mediterranean (Köppen Csb), notably the pattern of a wetter winter and moderately drier summer.

The climate is similar to nearby Aberdeen, situated slightly farther inland, but Ocean Shores experiences a narrower range of temperatures and is significantly less susceptible to extremes of heat in the summer, caused by hotter, inland air masses being pushed into the region.

| Climate data for Ocean Shores, Washington | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

76 (24) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

92 (33) |

85 (29) |

69 (21) |

64 (18) |

96 (36) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49 (9) |

51 (11) |

54 (12) |

56 (13) |

60 (16) |

63 (17) |

66 (19) |

67 (19) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

53 (12) |

48 (9) |

58 (14) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 38 (3) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

41 (5) |

46 (8) |

49 (9) |

52 (11) |

52 (11) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

40 (4) |

36 (2) |

44 (6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 11 (−12) |

9 (−13) |

22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

27 (−3) |

33 (1) |

32 (0) |

35 (2) |

30 (−1) |

24 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

7 (−14) |

7 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 11.10 (282) |

8.18 (208) |

8.08 (205) |

5.73 (146) |

3.60 (91) |

2.57 (65) |

1.36 (35) |

1.64 (42) |

2.57 (65) |

7.56 (192) |

12.09 (307) |

10.79 (274) |

75.27 (1,912) |

| Source: [9] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 800 | — | |

| 1980 | 1,692 | 111.5% | |

| 1990 | 2,301 | 36.0% | |

| 2000 | 3,836 | 66.7% | |

| 2010 | 5,569 | 45.2% | |

| 2020 | 6,715 | 20.6% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 7,344 | [4] | 9.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2020 census[edit]

As of the 2020 census, there were 6,715 people in 5,518 households, including 3,501 families, in the city.

2010 census[edit]

As of the 2010 census, there were 5,569 people in 2,707 households, including 1,657 families, in the city. The population density was 654.4 inhabitants per square mile (252.7/km2). There were 4,758 housing units at an average density of 559.1 per square mile (215.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 90.2% White, 0.9% African American, 2.1% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 4.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.2%.[11]

Of the 2,707 households 14.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.9% were married couples living together, 7.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 38.8% were non-families. 30.5% of households were one person and 14.4% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.06 and the average family size was 2.49.

The median age was 57.3 years. 12.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 4.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 14% were from 25 to 44; 37.5% were from 45 to 64; and 31.1% were 65 or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.3% male and 51.7% female.

2000 census[edit]

As of the 2000 census, there were 3,836 people in 1,789 households, including 1,198 families, in the city. The population density was 444.7 people per square mile (171.6/km2). There were 3,170 housing units at an average density of 367.5 per square mile (141.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.44% White, 0.60% African American, 2.19% Native American, 1.23% Asian, 0.10% Pacific Islander, 0.81% from other races, and 2.63% from two or more races. The city experienced an influx of West Midland residents in the late 1990s. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 1.75% of the population. 17.4% were of German, 13.9% Irish, 12.0% English, 9.6% American, and 8.0% Norwegian ancestry.

There were 1,789 households, of which 17.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.7% were married couples living together, 7.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.0% were non-families. 27.7% of households were one person and 12.6% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.55.

The age distribution was 16.8% under the age of 18, 4.6% from 18 to 24, 18.9% from 25 to 44, 31.7% from 45 to 64, and 28.0% 65 or older. The median age was 52 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.6 males.

The median household income was $34,643 and the median family income was $38,520. Males had a median income of $31,371 versus $25,393 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,192. About 9.8% of families and 12.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.1% of those under age 18 and 3.8% of those ages 65 or over.

Schools[edit]

Ocean Shores is served by the North Beach School District, which operates a high school and middle school located adjacent and two elementary schools in the area.

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

Ocean Shores is connected to the rest of the county by State Route 115, which connects Point Brown Avenue to State Route 109. The city is also served by Grays Harbor Transit bus route 60, which travels east to Hoquiam and Aberdeen and north to Taholah on the Quinault Indian Reservation, and a dial-a-ride route for in-city service.[12]

Ocean Shores Municipal Airport lies within the city limits, at 13 feet (4.0 m) above sea level.[13]

Tsunami protection[edit]

Ocean Shores lies at sea level and is vulnerable to potential tsunamis that would be created by a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. A bond measure to create a tsunami evacuation shelter and relocate a school to higher ground was rejected by voters in 2022. The state government and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) allocated $5 million in funds to construct a vertical evacuation shelter with capacity for 800 people; later designs are planned to be scaled back due to rising costs.[14]

Death on the Fourth of July[edit]

The book Death on the Fourth of July by David Neiwert documents a racially charged killing which took place in Ocean Shores on July 4, 2000.[15] A group of young Asian-American men who were visiting Ocean Shores spent that July 4 weekend there when they were attacked by a group of white men. One of the Asians, Minh Duc Hong, fatally stabbed Chris Kinison, who was from the Ocean Shores area. Hong was arrested and tried for manslaughter. His trial ended in a hung jury, 11–1 in favor of acquittal; prosecutors decided not to retry the case.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ "Mayor". osgov.com. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". Explore Census Data. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ "Ocean Shores". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ William Yardley (May 27, 2008), "Trying Again on a Coast That Defies Big Dreams", The New York Times

- ^ Hughes, John C.; Beckwith, Ryan Teague, eds. (2005). On the Harbor: From Black Friday to Nirvana. Stephens Press. p. 139. ISBN 9781932173505.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "weather.com". Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Grays Harbor Bus Book: Fall 2015 (PDF). Grays Harbor Transit. October 1, 2015. pp. 31–33. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Ocean Shores Municipal Airport, City of Ocean Shores

- ^ Doughton, Sandi (January 19, 2024). "Tsunami preparedness in WA: How Westport and its neighbors are leading the way". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ^ Neiwert, David (2004). Death on the Fourth of July: The Story of a Killing, a Trial, and Hate Crime in America (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6501-1.

- ^ "Hate Crimes: Asian youth freed in death of racist harasser". Spring 2001. Archived from the original on October 18, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

External links[edit]

- City of Ocean Shores official website

- "Asian American Groups Seek FBI Probe of Ocean Shores Stabbing", AsianWeek.com, October 2000 (story at the bottom of the page)