Columbus, Mississippi

Columbus, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Montage of significant city locations | |

| Nickname: Possum Town | |

| Motto: The Friendly City | |

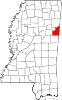

Location of Columbus, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 33°30′6″N 88°24′54″W / 33.50167°N 88.41500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Lowndes |

| Founded | 1821 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Keith Gaskin (I) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.88 sq mi (67.02 km2) |

| • Land | 25.05 sq mi (64.88 km2) |

| • Water | 0.83 sq mi (2.14 km2) |

| Elevation | 217 ft (66 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 24,084 |

| • Density | 961.48/sq mi (371.23/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 39701-39705 |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-15380 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0668721 |

| Website | Official website |

Columbus is a city in and the county seat of Lowndes County, on the eastern border of Mississippi, United States,[2] located primarily east, but also north and northeast of the Tombigbee River, which is also part of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. It is approximately 146 miles (235 km) northeast of Jackson, 92 miles (148 km) north of Meridian, 63 miles (101 km) south of Tupelo, 60 miles (97 km) northwest of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and 120 miles (193 km) west of Birmingham, Alabama.[3]

The population was 25,944 at the 2000 census and 23,640 in 2010.[4] The population in 2019 was estimated to be 23,573.[5] Columbus is the principal city of the Columbus Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of the larger Columbus-West Point Combined Statistical Area. Columbus is also part of the area of Mississippi called The Golden Triangle, consisting of Columbus, West Point and Starkville, in the counties of Lowndes, Clay and Oktibbeha.

History[edit]

The first record of the site of Columbus in Western history is found in the annals of the explorer Hernando de Soto, who is reputed to have crossed the nearby Tombigbee River on his search for El Dorado. However, the site does not enter the main continuity of United States history until December 1810, when John Pitchlynn, the U.S. Indian agent and interpreter for the Choctaw Nation, moved to Plymouth Bluff, where he built a home, established a farm, and transacted Choctaw Agency business.[citation needed]

After the Battle of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson recognized the urgent need for roads to connect New Orleans to the rest of the country. In 1817 Jackson ordered a road be built to provide a direct route from Nashville to New Orleans. His surveyor, Captain Hugh Young, chose a place on the Tombigbee River where high ground approached the river on both sides as the location for a ferry to be used for crossing the river when high water prevented fording the river. A military bridge was constructed where the present-day Tombigbee Bridge was later developed in Columbus, Mississippi. Jackson's Military Road opened the way for development in the area.[6]

Founding[edit]

Columbus was founded in 1819, and, as it was believed to be in Alabama, it was first officially recognized by an Alabama Legislative act as the Town of Columbus on December 6, 1819.[7] Before its incorporation, the town site was referred to informally as Possum Town, a name which was given by the local Native Americans, who were primarily Choctaw and Chickasaw. The name Possum Town remains the town's nickname among locals. The town was settled where Jackson's Military Road crossed the Tombigbee River 4 miles south of John Pitchlynn's residence at Plymouth Bluff. In 1820 the post office that had been at Pitchlynn's relocated in Columbus. Pitchlynn's which had been settled in 1810 became the town of Plymouth in 1836 and is now the location of an environmental center for Mississippi University for Women.[8] Silas McBee suggested the name Columbus; in return, a small local creek was named after him.[9]

The city's founders soon established a school known as Franklin Academy. It continues to operate and is known as Mississippi's first public school. The territorial boundary of Mississippi and Alabama had to be corrected as, a year earlier, Franklin Academy was indicated as being in Alabama. In fact, during its early post-Mississippi-founding history, the city of Columbus was still referred to as Columbus, Alabama.[citation needed]

Civil War and aftermath[edit]

During the American Civil War, Columbus was a hospital town. Its arsenal manufactured gunpowder, handguns and a few cannons. Because of this, the Union ordered the invasion of Columbus, but was stopped by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. This is substantiated in the book The Battle of West Point: Confederate Triumph at Ellis Bridge by John McBride. Many of the casualties from the Battle of Shiloh were brought to Columbus. Thousands were eventually buried in the town's Friendship Cemetery.[citation needed]

One of the hospitals was located at Annunciation Catholic Church, built in 1863 and still operating in the 21st century. The decision of a group of ladies to decorate the Union and Confederate graves with flowers together on April 25, 1866, is an early example of what became known as Memorial Day. A poet, Francis Miles Finch, read about it in the New York newspapers and commemorated the occasion with the poem "The Blue and the Grey".[10] Bellware and Gardiner noted this observance of the holiday in The Genesis of the Memorial Day Holiday in America (2014). They recognized the events in Columbus as the earliest manifestation of an annual spring holiday to decorate the grave of Southern soldiers. While the call was to celebrate on April 26, several newspapers reported that the day was the 25th, in error.[11]

As a result of Forrest preventing the Union Army from reaching Columbus, its antebellum homes were spared from being burned or destroyed, making its collection second only to Natchez as the most extensive in Mississippi.[12][page needed] These antebellum homes may be toured during the annual Pilgrimage, in which the Columbus residences open their homes to tourists from around the country.[citation needed]

When Union troops approached Jackson, the state capital was briefly moved to Columbus before moving to a more permanent home in Macon.[13]

During the war, Columbus attorney Jacob H. Sharp served as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. After the war, he owned the Columbus Independent newspaper. He was elected to two terms in the State House, serving four years representing the district in the Mississippi House of Representatives.[14]

WPA mural[edit]

The mural Out of the Soil was completed in 1939 for the Columbus post office by WPA Section of Painting and Sculpture artist Bealah Betterworth.[15] Murals were produced from 1934 to 1943 in the United States through "the Section" of the U.S. Treasury Department.[citation needed]

20th century[edit]

Columbus has hosted Columbus Air Force Base (CAFB) since World War II. CAFB was founded as a flight training school. After a stint in the 1950s and 1960s as a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base (earning Columbus a spot in Soviet Union target lists), CAFB returned to its original role. Today, it is one of only four basic Air Force flight training bases in the United States, and prized as the only one where regular flight conditions may be experienced. Despite this, CAFB has repeatedly hung in the balance during Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) hearings.[citation needed]

Columbus boasted a number of industries during the mid-20th century, including the world's largest toilet seat manufacturer, Sanderson Plumbing Products, and major mattress, furniture and textile plants. Most of these had closed by 2000. A series of new plants at the Golden Triangle Regional Airport, including the Severstal mill, the American Eurocopter factory, the Paccar engine plant and the Aurora Flight Sciences facility, are revitalizing the local economy.[citation needed]

Recent history[edit]

On June 12, 1990, a fireworks factory in Columbus exploded, detonating a blast felt as far as 30 miles away from Columbus. Two workers were killed in the blast.[16][17]

On February 16, 2001, straightline winds measured at 74 miles per hour destroyed many homes and trees but resulted in no fatalities. The city was declared a federal disaster area the next day by President George W. Bush. On November 10, 2002, a tornado hit Columbus and caused more damage to the city,[18][19] including the Mississippi University for Women.[20][21]

In 2010, Columbus won a Great American Main Street Award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[22]

In February 2019, Columbus took a direct hit from an EF-3 tornado that caused devastating damage to homes and businesses and killed one woman after a structure fell on her.[23]

Geography[edit]

The city is located approximately 10 mi (16 km) west of the Mississippi-Alabama state line along U.S. Route 82, U.S. Route 45, and numerous state highways. US 82 leads southeast 29 mi (47 km) to Reform, Alabama and west 25 mi (40 km) to Starkville. US 45 leads south 32 mi (51 km) to Macon and north 28 mi (45 km) to Aberdeen. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 22.3 square miles (58 square kilometers), of which 21.4 square miles (55 square kilometers) is land and 0.9 square miles (2.3 square kilometers) is water. Large lakes and rivers are nearby, such as the Buttahatchee River in northern Lowndes County that defines the border between Lowndes and Monroe counties; in the middle of the City of Columbus and Lowndes County lies the Luxapallila Creek, and the Tombigbee River with the John C. Stennis Lock and Dam impounding Columbus Lake. Columbus is a relatively flat place in the northern part of Lowndes County, as the land rises for a short period of time into hills and bluffs, in the southern/eastern part of the county, the land has rolling hills that quickly turn into flatland floodplains that dominate this county. This county lies in the Black Prairie Geographic Region, and the Northeastern Hills Region of the state/area. Prairies, forests and floodplain forests lie here. The soil quality is poor in the eastern part of the county, otherwise the soil is relatively fertile. Columbus and the surrounding areas are listed as an Arbor Day Hardiness Zone 8a (10 to 15 °F or −12.2 to −9.4 °C); note that temperatures in 2010 reached 11 °F (−12 °C), but the USDA Hardiness Zones list the area as zone 7b (5 to 10 °F or −15.0 to −12.2 °C).[24]

Climate[edit]

| Climate data for Columbus, Mississippi (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1903–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

100 (38) |

108 (42) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

104 (40) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 55.8 (13.2) |

61.2 (16.2) |

69.7 (20.9) |

77.6 (25.3) |

84.9 (29.4) |

90.9 (32.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

93.4 (34.1) |

88.4 (31.3) |

78.3 (25.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

58.1 (14.5) |

76.5 (24.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 45.8 (7.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

58.0 (14.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

73.2 (22.9) |

80.2 (26.8) |

83.2 (28.4) |

82.6 (28.1) |

77.0 (25.0) |

66.2 (19.0) |

54.6 (12.6) |

48.1 (8.9) |

65.4 (18.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.8 (2.1) |

39.2 (4.0) |

46.3 (7.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

72.7 (22.6) |

71.9 (22.2) |

65.6 (18.7) |

54.0 (12.2) |

42.7 (5.9) |

38.1 (3.4) |

54.2 (12.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−3 (−19) |

13 (−11) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

53 (12) |

50 (10) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

9 (−13) |

−4 (−20) |

−7 (−22) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.45 (138) |

5.69 (145) |

5.32 (135) |

5.81 (148) |

4.02 (102) |

4.40 (112) |

4.68 (119) |

4.50 (114) |

3.20 (81) |

3.63 (92) |

4.35 (110) |

5.59 (142) |

56.64 (1,439) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 100.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Source: NOAA[25][26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 2,611 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,308 | 26.7% | |

| 1870 | 4,812 | 45.5% | |

| 1880 | 3,955 | −17.8% | |

| 1890 | 4,559 | 15.3% | |

| 1900 | 6,484 | 42.2% | |

| 1910 | 8,988 | 38.6% | |

| 1920 | 10,501 | 16.8% | |

| 1930 | 10,743 | 2.3% | |

| 1940 | 13,645 | 27.0% | |

| 1950 | 17,172 | 25.8% | |

| 1960 | 24,771 | 44.3% | |

| 1970 | 25,795 | 4.1% | |

| 1980 | 27,503 | 6.6% | |

| 1990 | 23,799 | −13.5% | |

| 2000 | 25,944 | 9.0% | |

| 2010 | 23,640 | −8.9% | |

| 2020 | 24,084 | 1.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] | |||

2020 census[edit]

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 7,460 | 30.97% |

| Black or African American | 15,345 | 63.71% |

| Native American | 37 | 0.15% |

| Asian | 250 | 1.04% |

| Pacific Islander | 4 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 350 | 2.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 458 | 1.9% |

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 24,084 people, 9,572 households, and 5,348 families residing in the city.

2010 census[edit]

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 23,640 people living in the city. 60.0% were African American, 37.4% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from some other race, and 1.1% of two or more races. 1.4% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2000 census[edit]

Columbus' population has grown steadily since the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1900, 6,484 people lived in Columbus; in 1910, 8,988; in 1920, 10,501; and in 1940, 13,645. As of the census[29] of 2000, there were 25,944 people, 10,062 households, and 6,419 families living in the city. The population density was 1,211.5 people per square mile (467.8 people/km2). There were 11,112 housing units at an average density of 518.9 per square mile (200.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city is 43.62% White, 54.41% African American, 0.10% Native American, 0.56% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.51% from other races, and 0.79% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.13% of the population.

There were 10,062 households, out of which 29.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.0% were married couples living together, 21.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.2% were non-families. 31.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.07.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.0% under the age of 18, 12.0% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $27,393, and the median income for a family was $37,068. Males had a median income of $30,773 versus $20,182 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,848.

Economy[edit]

Major Employers:

- Columbus Air Force Base.

- Baptist Memorial Hospital - Golden Triangle.

- Mississippi University for Women.

- Columbus Municipal School District.

- Lowndes County School District.

- International Paper Columbus Mill and Columbus Modified Fiber.

- Steel Dynamics, Inc. (steel manufacturer).

- Paccar (diesel engines).

- American Eurocopter (military aircraft).

- Baldor (electric motors).

- Nouryon (sodium chlorate production).

- Aurora Flight Sciences (unmanned defense systems).

- Stark Aerospace (unmanned defense systems).

- Columbus / Nammo-Talley (defense systems).

- Valmet (paper machine rolls and roll covers).

Arts and culture[edit]

Columbus is the birthplace of playwright Tennessee Williams, whose grandfather was the priest of St. Paul's Episcopal Church. Williams was born in the rectory on Main Street, which is now the Tennessee Williams Home Museum and Welcome Center.[30][31]

Education[edit]

Columbus is home to a state university, the Mississippi University for Women. The MUW campus is also home to the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science, a state-funded public boarding school for academically gifted high school juniors and seniors.[citation needed]

The city's public high school (under the Columbus Municipal School District) is Columbus High School, located in the eastern part of town. It is the largest high school in the city and fifth largest in the state, enrolling approximately 1370 students. Columbus High School was formed by the merger of the city's two previous high schools, Stephen D. Lee High School and Caldwell High School; the schools were merged in 1992 and the campuses in 1997. Columbus is also home to the oldest public elementary school in Mississippi, Franklin Academy Elementary, founded in 1821.[citation needed]

Desegregated in 1970, Lee High School received a state award for the high school with the best race relations.[citation needed] Prior to desegregation, the school formed a race relations committee consisting of black and white students who could discuss issues and determine how to handle certain situations. For instance, the students decided to have both white and black homecoming courts so as to prevent sides being taken along racial lines. However, black students were allowed to vote for the white homecoming court and vice versa. The school went undefeated in football in 1970, which helped unite the student body. Students were ranked based on achievement score tests and divided into three groups, in order to allow each group to learn at their own pace.[citation needed] This practice was in place prior to integration. It was continued after integration for a period, but such tracking was later ruled to be unconstitutional by a Federal court, because it was based on biased testing. It did not take into account differences in preparation in earlier grades.[citation needed]

The Lowndes County School District operates three high schools—Caledonia, New Hope, and West Lowndes—fed by similarly named elementary and middle schools.[citation needed]

Columbus has several private schools, including:

- Columbus Christian Academy, formerly Immanuel Christian School (K-3 through 12)

- Heritage Academy (Christian, K-12)

- Annunciation Catholic School (Catholic, K-8)

- Victory Christian Academy (Christian, K-12)

- Palmer Home for Children (orphanage)

Media[edit]

Columbus' city newspapers are the daily (except Saturdays) Commercial Dispatch, the weekly (Thursdays) Columbus Packet and the internet-only paper, Real Media (formerly The Real Story). One television station, WCBI-TV 4, the CBS affiliate, is located in the city's historic downtown area; it broadcasts FOX and MyNetworkTV programming on digital subchannels.

Columbus is also served by television stations from the Columbus / Tupelo / West Point DMA. These include NBC affiliate WTVA 9, its DT2 subchannel which is the market's ABC affiliate, and CW affiliate WLOV-TV 27.

Radio Stations include:

- 103.1 Sports Talk/ESPN Radio

- 94.1 Top 40

- 99.9 Rock

- 92.1 Hip-Hop & R&B

- 100.9 Talk Radio (Supertalk Mississippi)

- 93.3 Easy Listening/Top 40

- 104.5 Christian radio/KLOVE

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]

Columbus lies on U.S. Highways 82 and 45. It is also served by state highways 12, 50, 69, and 182. Columbus is the eastern terminus of the Columbus and Greenville Railway; it is also served by the BNSF Railway (on the original right-of-way of the St. Louis - San Francisco Railway), the Norfolk Southern, and the Alabama Southern Railroad (using the original right-of-way of the Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad). The local airport is Golden Triangle Regional Airport. The airport currently has three flights a day to Atlanta.

The city is located on the east bank of the Tombigbee River and the associated Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. Columbus Lake, formed by the John C. Stennis Lock and Dam, is approximately two miles north of downtown. The Luxapalila Creek runs through the town, separating East Columbus from Columbus proper (both are within city limits). The Lux, as it is locally known, joins the Tombigbee about three miles south of downtown.[citation needed]

Notable people[edit]

- Mike Adams (columnist)

- Henry Armstrong, world boxing champion[32]

- Roy Ayres, pedal steel guitar player[33]

- Red Barber, sports commentator[34]

- William T. S. Barry, congressman from Mississippi[35]

- Homer "Billy" Brewer, professional football player[36]

- Terry W. Brown, president pro tempore of the Mississippi Senate[37]

- Tyson Brummett, professional baseball player[38]

- Corey Cott, actor and singer

- James E. Darnell, biologist[39]

- Jacob M. Dickinson, U.S. Secretary of War from 1909 to 1911[40]

- Doughboy, record producer[41]

- Elbert Drungo, professional football player[42]

- Ean Evans, bass player for Lynyrd Skynyrd; moved to Columbus[43]

- Leslie Frazier, professional football player and coach[44]

- Charles Fredericks, actor[45]

- Luther Hackman, professional baseball player[46]

- Arthur Cyprian Harper, 26th mayor of Los Angeles[47]

- Robert Ivy, chief executive officer of the American Institute of Architects[48]

- Sam Jethroe, first black baseball player on the Boston Braves roster

- Edward J. C. Kewen, member of California State Legislature and first attorney general of California[49]

- Stephen D. Lee, Confederate general, first president of Mississippi State University[50]

- Jasmine Murray, singer, Miss Mississippi 2014[51][52]

- Bobby Richards, professional football player[53]

- Andre Rush, celebrity chef and veteran[54]

- Jacob H. Sharp, lawyer, newspaperman, politician, and Confederate general; moved to Columbus[55]

- Jeff Smith, member of Mississippi House of Representatives[56]

- Ruby Jane Smith, bluegrass fiddler

- Cordella Stevenson, African-American woman who was raped and lynched by a mob of white men in Columbus in 1915[57]

- William N. Still Jr., maritime historian

- Jim Thomas, professional football player

- Sedric Toney, professional basketball player[58]

- Guy M. Townsend, U.S. Air Force brigadier general, test pilot, and combat veteran[59]

- Robert L. Turner, member of Wisconsin State Assembly[60]

- James R. Williams, lawyer, politician and jurist[61]

- Tennessee Williams, playwright[62]

- Andrew Wood, musician[63]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Columbus Convention and Visitors Bureau Archived April 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Columbus (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Quickfacts.census.gov. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Ward, Rufus (November 4, 2013). "Ask Rufus: Andrew Jackson's Military Road". Commercial Dispatch. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Toulmin, Harry. 1825. Cahawba, Alabama: Ginn and Curtis.

- ^ Sherman, Harry L (2007). A Very Remarkable Bluff. Mississippi University for Women. pp. 34–45.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar, ed. Mississippi, Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons arranged in Cyclopedic Form in three volumes. Vol. 2. Atlanta: Southern Historical Publishing Association, 1907, pp. 134-137.

- ^ Fallows, Deborah. "A Real Story of Memorial Day" Archived 2017-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, The Atlantic, May 2014

- ^ Bellware, Daniel; Richard Gardiner (2014). The Genesis of the Memorial Day Holiday in America. Columbus State University. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-692-29225-9.

- ^ John McBride, The Battle of West Point: Confederate Triumph at Ellis Bridge, The History Press, 2013

- ^ "Governor's Mansion during the Civil War". Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, page 481. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- ^ Burnett, Garthia Elena (January 15, 2011). "Post office mural raises questions of racial sensitivity". The Dispatch. Columbus, Mississippi. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "Two Killed as Explosions Destroy Fireworks Factory". Los Angeles Times. June 13, 1990. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Explosions At Mississippi Fireworks Plant Kill Two". Apnewsarchive.com. June 12, 1990. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ [1] Archived November 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Amy, Jeff (February 14, 2013). "Tornado damage to University of Southern Mississippi estimated in tens of millions - U.S. News". Usnews.nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ [2] Archived November 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Welcome to the Columbus Main Street Website". Columbus Main Street. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ "Tornado Victim Remembered As Loving Mother, Daughter And Caring Person". WCBI News. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Mississippi USDA Hardiness Zone Map". Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Columbus, MS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Swoope, Jan (March 20, 2021). "Columbus to host Tennessee Williams' birthday celebration". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Tennessee Williams Birthplace - Columbus, Mississippi".

- ^ "Biography". Henryarmstrong.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2009.

- ^ "The Inductees". The Steel Guitar Hall Of Fame. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018.

- ^ "1978 Ford C. Frick Award Winner Red Barber". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013.

- ^ "BARRY, William Taylor Sullivan, (1821 - 1868)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Billy Brewer". NFL.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Terry W. Brown". Mississippi Senate. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013.

- ^ "Tyson Brummett". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017.

- ^ ""Vital Information" - Laureates of the 2002 National Medal of Science". National Science Foundation. October 29, 2003. Archived from the original on May 28, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ "Jacob McGavock Dickinson". U.S. Army Center of Military History. March 6, 2001. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "Doughboy Beatz Discography and Songs". Discogs.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Elbert Drungo". NFL.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Ean Evans, Lynyrd Skynyrd Bassist, Dead At 48". HuffingtonPost.com. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on December 9, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "Leslie Frazier". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Charles Fredericks". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Luther Hackman". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Arthur C. Harper, Former Los Angeles Mayor, Dies". Los Angeles Times. December 26, 1948. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014.

- ^ "About". www.aia.org. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Edward J. C. Kewen, 1st Attorney General". State of California Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Stephen D. Lee Home and Museum (c.1847)". Columbus Convention and Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on October 20, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, Billy (February 24, 2009). "A Star in the Making?". Clarion Ledger.

- ^ Bradley-Phillips, Terricha. "Miss Riverland Jasmine Murray crowned Miss Mississippi 2014". Hattiesburg American. Hattiesburg American. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ "Bobby Richards". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Muscle-bound chef has served 4 presidential administrations". AP NEWS. November 11, 2018. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "About Columbus". Cam Club. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Jeff Smith". Project Vote Smart. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "RAPE, LYNCH NEGRO MOTHER". Chicago Defender. December 18, 1915.

- ^ "Sedric Toney". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Brigadier General Guy M. Townsend". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Members of State Legislature" (PDF). Wisconsin State Legislature. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "UA Board Approves Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters for the Honorable Judge James R. Williams". University of Akron. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ "Tennessee Williams Welcome Center". City of Columbus. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Biography". Allmusic. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.