RAF Advanced Air Striking Force

| RAF Advanced Air Striking Force | |

|---|---|

A Fairey Battle light bomber | |

| Active | 24 August 1939 – 26 June 1940 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Type | tactical bomber and fighter aircraft |

| Engagements | Battle of France |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Air Vice-Marshal Patrick Playfair |

| Aircraft flown | |

| Bomber | Fairey Battle Bristol Blenheim |

| Fighter | Hawker Hurricane |

The RAF Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) comprised the light bombers of 1 Group RAF Bomber Command, which took part in the Battle of France during the Second World War. Before hostilities began, it had been agreed between the United Kingdom and France that in case of war, the short-range aircraft of Bomber Command would move to French airfields to operate against targets in Nazi Germany. The AASF was formed on 24 August 1939 from the ten squadrons of Fairey Battle light bombers of 1 Group under the command of Air Vice-Marshal Patrick Playfair and was dispatched to airfields in the Rheims area on 2 September 1939.

The AASF was answerable to the Air Ministry and independent of the British Expeditionary Force. For unity of command, the AASF and the Air Component of the BEF (Air Vice-Marshal Charles Blount), came under the command of British Air Forces in France (Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Barratt) on 15 January 1940. Using the bombers for attacks on strategic targets in Germany was set aside, due to Anglo-French reluctance to provoke German retaliation; attacks on German military forces and their communications were substituted.

The Battle of France began with the German invasion of the Low Countries on 10 May 1940. The Battle squadrons suffered 40 per cent losses on 10 May, 100 per cent on 11 May and 63 per cent on 12 May. In 48 hours the number of operational AASF bombers fell from 135 to 72. On 14 May the AASF made a maximum effort, 63 Battles and eight Bristol Blenheims attacked targets near Sedan. More than half the bombers were lost, bringing AASF losses to 75 per cent. The remaining bombers began to operate at night and periodically by day, sometimes with fighter escorts.

From 10 May to the end of the month, the AASF lost 119 Battle crews killed and 100 aircraft. Experience, better tactics and periods of bad weather from 15 May to 5 June led to losses of 0.5 per cent, albeit with a similar reduction in effectiveness. On 14 June, the remaining Battles returned to Britain; the Hurricane squadrons returned on 18 June and rejoined Fighter Command. The AASF was dissolved on 26 June, the Battles returning to 1 Group, Bomber Command, to prepare for operations against a German invasion, along with the rest of the Royal Air Force.

Background[edit]

1930s Anglo-French air policy[edit]

Once British rearmament began, the air policy of the British government was to have air defences sufficient to defeat an attack and an offensive force equal to that of the Luftwaffe. With no land border to defend, British resources had been concentrated on radar stations, anti-aircraft guns and increasing the number of the most modern fighter aircraft. If Germany attacked, the British intended to take the war to the Germans by attacking strategically important targets with its heavy bombers, types unsuitable for operations in direct support of land forces.[1] Implementation of the policy required a considerable number of first-class fighter aircraft to defeat an attacker and bombers to destroy ground targets.[2]

In 1938 the RAF expansion programme was intended to provide means for the air defence of Britain and for counter-offensive operations against Germany. Army co-operation received few resources and no plans were made for RAF participation in mass land operations or the dispatch abroad of large expeditionary air forces. The Western Plan was devised by the Air Ministry for mobilisation and the deployment of squadrons to their wartime airfields. Provision was made for the immediate dispatch of an Advanced Air Striking Force of ten squadrons to France, followed by a second echelon of ten more. Refuelling facilities were also planned for other squadrons, the arrangements for transport and servicing being co-ordinated with the army; thought was also given to basing squadrons in Belgium if it was invaded by Germany.[2]

In February 1939, the British Cabinet had authorised joint planning with the French and preferably with Belgium and the Netherlands in case of war with Germany, Italy and Japan. Two weeks before the first meeting, Germany occupied the rump of Czechoslovakia; war preparations took on a new urgency and staff conversations began on 29 March 1939.[3] Agreement was reached with France to base the AASF on French airfields but only to bring them closer to their intended targets in Germany, until longer-range types became available.[4] French strategy emphasised the defence of the national territory and Allied efforts were expected to give equal emphasis but the British refused to stake everything on the success of a defensive campaign against the Germans in France. The different circumstances of the two countries led the French to rely on a mass land army, with air defence a secondary concern, the Armeé de l'Air was hampered in the late 1930s by the slow progress of its re-equipment, lacking anti-aircraft guns, sufficient fighter aircraft and the means to detect and track enemy aircraft. Observation services relied on civilian telephones and in October 1939, the Armeé de l'Air had only 549 fighters, 131 of which were considered anciens (obsolete).[1]

Lack of aircraft led the French to advocate a bombing policy of tactical co-operation with the armies, attacking German forces and communications in the front line, rather than the strategic bombing of Germany, for fear of retaliation.[1] From the spring of 1939, arrangements were made for the reception of the AASF, the defence of British bases in France, bombing policy in support of ground forces confronting a German attack in the Benelux countries, and operations against the Luftwaffe. A supply of British bombs was dumped near Reims, disguised as a sale to the Armeé de l'Air. Discussion of strategic air operations against the German war economy was delayed because the British did not expect to begin such operations as soon as war was declared and because the French had no bombers capable of them. In the last days of peace, the Cabinet limited air bombardment strictly to military objectives which were narrowly defined and a joint declaration was issued concerning the policy of following of the rules of war pertaining to poison gas, submarine warfare and air attacks on merchant ships to avoid provoking the Germans while the Anglo-French air forces were being built up.[5]

August 1939[edit]

On 24 August 1939, the British government gave orders for the armed forces partially to mobilise and on 2 September No. 1 Group RAF (Air Vice-Marshal Patrick Playfair) sent its ten Fairey Battle day-bomber squadrons to France according to plans made by the British and French earlier in the year. The group was the first echelon of the AASF and flew from RAF Abingdon, RAF Harwell, RAF Benson, RAF Boscombe Down and RAF Bicester. Group headquarters became the AASF when the order to move to France was received and the home station HQs became 71, 72 and 74–76 Wings. The Bristol Blenheims of No. 2 Group RAF were to become the second echelon as 70, 79 and 81–83 Wings, flying from RAF Upper Heyford, RAF Wattisham, RAF Watton, RAF West Raynham and RAF Wyton; 70 Wing with 18 and 57 squadrons was converting from Battles to Blenheims and intended for the Air Component once the re-equipment was complete.[7] On 3 September, as the British government declared war on Germany; the AASF Battle squadrons were getting used to their French airfields, which were somewhat rudimentary compared to their well-developed Bomber Command stations, some having to wait for the French to deliver aviation fuel.[8]

September[edit]

Strategic bombing operations did not take place as the Luftwaffe and Allied strategic bombers observed a tacit truce. The French tried to divert German resources from their Invasion of Poland with the Saar Offensive (7–16 September), in which the Battle squadrons were to participate. The main Luftwaffe bases were too far inside Germany but airstrips, supply dumps and reserves would be well within the range of the Battles. The British and French governments feared that they had more to lose by courting German retaliation but this deprived the Battle squadrons of a chance to test their equipment and tactics. The preparations did establish that Battles would attack targets within 10 mi (16 km) of the front line, including fleeting opportunities, much against the wishes of Group Captain John Slessor, a former Director of Plans at the Air Ministry, who stressed that the Battle crews were not trained for close support. Other officers thought that "...it is about as far as the Battle will be able to get with a return ticket".[9] Playfair had the fuselage fuel tank removed from AASF Battles and the bomb bays were to be modified to carry 40 lb (18 kg) anti-personnel bombs, once the equipment arrived in November.[10]

Battle reconnaissances[edit]

Neither the French nor the British wanted the AASF to sit idle and the Battles began to conduct "high-altitude", formation, photographic reconnaissance sorties, to map the German front line but the Battle had a service ceiling of only 25,000 ft (7,600 m) and needed to be much lower for formation flying.[10] Battle sorties began on the morning of 10 September, three aircraft of 150 Squadron flying inside Allied lines and photographing obliquely. On 19 September the Battles began to fly beyond the front line, 10 mi (16 km) at first, then 20 mi (32 km). Playfair, mindful of the risk, tried to time sorties to coincide with French fighter operations in the vicinity and wanted close escorts if German fighters were around. Three Battles from 103 Squadron and three from 218 Squadron reconnoitred on 17 September, the Battles encountering intermittent anti-aircraft fire (FlaK). Bad weather led to a two-day lull, then on 20 September, three Battles from 88 Squadron west of Saarbrücken were attacked by three Messerschmitt Bf 109Ds, which shot down two of the Battles, whose defensive fire was ineffective. One Battle pilot crash-landed and his aircraft caught fire, killing the observer and gunner; the other Battle crashed the same way and the third Battle was hit in its fuel tanks and incinerated the crew.[11][a]

Playfair concluded that Battles should receive an escort anywhere near the front line but the Air Ministry rejected the claim that more fighters were necessary and he had to ask the French instead.[13] The Chief of Staff of the French Air Force (Chef d'état-major de l'Armée de l'air), Général d'Armée Aérienne Joseph Vuillemin, was short of fighters but promised to help, provided the British helped themselves. At a meeting on 28 September, the British representative repeated the claim that tight formation-flying and collective firepower obviated the need for escorts and Vuillemin cancelled French co-operation. Two days later, five Battles from 150 Squadron on reconnaissance near Saarbrücken and Merzig, were attacked by eight Bf 109Es. The Battles closed up but four were shot down, most in flames. The surviving Battle pilot ran for home and crashed on landing but saved his crew. The squadron immediately fitted its aircraft with an extra rear-facing gun in the bomb-aiming position against attacks from below and behind; in England the Air Ministry blamed the Battle, rather than faulty tactics and equipment and declared it obsolete. For protection against fighter attack, 85 lb (39 kg) of armour for each aircraft was rushed to France and 15 and 40 squadrons returned to Britain to convert to Blenheims, being replaced by 114 and 139 squadrons which were already flying the type.[14]

AASF tactical changes[edit]

In England, discussions for a second-generation Battle took place and the AASF was ordered to train Battle crews for low-level tactical operations to avoid the Bf 109s. The crews practised attacks on road vehicles from as low as 50 ft (15 m) and some rehearsals had fighter escorts, a new task given to the AASF Hurricane squadrons. Air Chief Marshal Robert Brooke-Popham, having been dug out of retirement, inspected the RAF in France and organised a meeting with Fairey, the Air Ministry and crews from 150 Squadron, to discuss protection against ground fire. Fairey considered that the Battle was already at its maximum weight and that self-sealing fuel tanks and armour could be added only by reducing the bomb load or range. No one in Britain knew that the Battles in France had already had their fuselage fuel tanks removed, which had saved 300 lb (140 kg). Fairey suggested a ventral machine-gun [40 lb (18 kg)], crew armour [100 lb (45 kg)], safer fuel tanks [100 lb (45 kg)], armour around the rear gunner [25 lb (11 kg)] and another 80 lb (36 kg) of ventral (underside) armour. Only the 25 lb (11 kg) armour plate for the rear gunner needed to be manufactured and the extra armour was ordered to France as soon as possible.[15]

Battle fuel tanks were to be given the French Semape coating, which easily plugged holes from rifle-calibre bullets and also gave some protection from 20 mm (0.79 in) cannon fire. Semape would use up the 100 lb (45 kg) allotted for fuel tank protection and was still under test but 26 lb (12 kg) of armour plates were added to the rear of the tanks against hits from behind. On 18 December, twenty-two Vickers Wellington medium bombers were sent to attack German ships in the Battle of the Heligoland Bight and eighteen were lost, many shot down in flames; some of those not shot down ran out of fuel from punctured fuel tanks. The fitting of self-sealing tanks became a crisis measure for Bomber Command and took precedence over the Battle modification, especially as their existing tanks had been armoured against hits from behind and the conversion was put back to March 1940. The extra armour decided on in September was apparently sent to France but never fitted to the Battles.[16]

Operational instructions issued by BAFF included a warning that

Bomber aircraft have proved extremely useful in support of an advancing army, especially against weak anti-aircraft resistance, but it is not clear that a bomber force used against an advancing army well supported by all forms of anti-aircraft defence and a large force of fighter aircraft, will be economically effective.[17]

The RAF had tried to improve the performance of its aircraft; streamlining the Blenheim had added 15 mph (24 km/h) to its speed. To remedy the vulnerability of Battles to attacks from below, a rear-facing machine-gun was fitted to the bomb-aimer's position but "...it needed a contortionist to fire it....",

To enable the gunner to fire backwards behind the tail, the gun swivels on a mounting fixed in the bombing aperture and is made capable of firing upside down, being provided with extra sights which will work in this position. The gunner wears a special harness enabling him to assume an almost upside-down position.

Fairey designed a well in the floor of the bomb aiming position for the gunner to lie prone facing the rear but the change would need three months for development and testing. With 500 Battles in storage, the modifications could be done at Fairey and the aircraft swapped with those in France without interfering with AASF operations but the idea was shelved.[19]

To speed production of new aircraft, a review was held to strip existing machines of superfluous equipment and the committee suggested that for tactical bombing, the Battle autopilot [80 lb (36 kg)], night flying gear [44 lb (20 kg)], bomb sight [34 lb (15 kg)] and the navigator–bomb-aimer [200 lb (91 kg)] could be dispensed with, saving 358 lb (162 kg), which would allow the fitting of more forward-firing guns with no net increase in weight. The Air Ministry prevaricated and the equipment was not removed, the Ministry even deprecating the use of the existing forward-firing gun, which was supposed to be reserved for engagements with German fighters, not for strafing unless circumstances were exceptional.[20]

October–December[edit]

On 11 October, Luftwaffe Dornier Do 17 bombers begin to cross the lines at high altitude and one flew at 20,000 ft (6,100 m) over the 1 Squadron AASF fighter base at Vassincourt, only to be shot down near Vausigny. The two Hawker Hurricane fighter squadrons (67 Wing) were part of the AASF to provide fighter protection for their bases, with another squadron of Hurricanes in England made available as a reinforcement.[21] The second echelon squadrons of 2 Group, with seven Blenheim squadrons and two Armstrong Whitworth Whitley medium bomber squadrons, stood ready to move to France if the Germans attacked. At 10:00 a.m., on 8 November 73 Squadron shot down a Do 17, its first victory of the war. To counter the high-flying Dorniers, seven fighter sectors were established on 21 November in Zone d'Opérations Aériennes Nord (ZOAN, "Air Zone North") and Zone d'Opérations Aériennes Est (ZOAE, "Air Zone East") and on 22 November, 1 Squadron shot down two Do 17s in the morning, a Hurricane force-landing after being hit in the engine and early in the afternoon, three Hurricanes over Metz shared a Heinkel He 111 with the Armée de l'Air, one Hurricane being damaged in a collision with a French fighter; 73 Squadron claimed two Dorniers shot down and one damaged, shared with French fighters. For most of December, flying was washed out by bad weather but on 21 December, two Hurricanes shot down a Potez 637 over Villers-sur-Meuse, with only one survivor. The next day, five Bf 109s bounced three 73 Squadron Hurricanes and shot two down.[22]

Prelude[edit]

January 1940[edit]

British Air Forces in France[edit]

| Aircraft | Squadron |

|---|---|

| In France | (first echelon) |

| Battle | 12, 15, 40, 88, 103, 105 142, 150, 218, 226 |

| Blenheim IV | 114, 139 (from December 1939) |

| Hurricane[b] | 1, 73 (501 from 11 May 1940) |

| In England[c] 2 Group |

(second echelon) |

| Blenheim IV | 21, 82, 107, 110 |

| 4 Group | |

| Whitley | 77, 102 |

| Losses | (sources vary)[26] |

| AASF | Battle:.....137 Blenheim: 37; Total: 174 |

| 2 Group | Blenheim:....................98 |

| Total losses | 272 |

On the declaration of war, the Air Component had come under the command of Lord Gort the Commander-in-Chief of the BEF and the AASF remained under Bomber Command control but based with the Armée de l'Air. Thought had been given to liaison and Air Missions had been installed in the main Allied headquarters but training exercises showed that communication was inadequate. In January 1940, command of the AASF and the Air Component was unified under Air Marshal Arthur Barratt as Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief British Air Forces in France (BAFF), the Air Component being detached from the BEF while remaining under its operational control and Bomber Command losing the AASF, since the Battle would not be used for strategic bombing.[27][28][d] Barratt was charged with giving "full assurance" to the BEF of air support and to provide the BEF with

...such bomber squadrons as the latter may, in consultation with him, consider necessary from time to time.

Since the British held only a small part of the Western Front, Barratt was expected to operate in the context of the immediate needs of the Allies. In France the new arrangement worked well but the War Office and the Air Ministry never agreed on what support should be given to the Field Force of the BEF.[30] When Air Marshal Charles Portal replaced Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt as AOC-in-C Bomber Command on 3 April, he prevented the second echelon of the AASF from going to France, with the agreement of Cyril Newall, the Chief of the Air Staff. Portal took the view that fifty Blenheims attempting to attack an advancing army, using out of date information, could not achieve results commensurate with the expected losses.[31] On 8 May he wrote,

I am convinced that the proposed employment of these units is fundamentally unsound, and if it is persisted in it is likely to have disastrous consequences on the future of the war in the air.[32]

The airfields occupied by the first echelon were still being equipped for operations and would become dangerously congested if the second echelon arrived. Barratt questioned the wisdom of an assumption that because the AASF was behind the Maginot Line, mobility was less important than that of the Air Component and approval was eventually given to make the AASF semi-mobile. Motorisation came too late and the AASF had to beg, steal or borrow French vehicles when squadrons changed base; by late April, the AASF strength had risen to 6,859 men.[33]

February–March[edit]

More flying was possible in January but the air forces spent most of February on the ground, with many of the aircrews on leave. The weather became much better for flying and on 2 March a Dornier was shot down by two 1 Squadron Hurricanes, one of the British pilots being killed while attempting a forced landing after being hit in the engine by return fire; next day, British fighters shot down a He 111. On 3 March, two 73 Squadron pilots escorting a Potez 63 at 20,000 ft (6,100 m) spotted seven He 111s 5,000 ft (1,500 m) higher and gave chase, only to be attacked by six Bf 109s. A Bf 109 overshot one of the Hurricanes, which fired on it as it drew ahead. The Bf 109 fell, leaving a trail of black smoke, the eleventh victory for the squadron. The Hurricane was hit by the third Bf 109 and the pilot only just managed to reach a French airfield and make an emergency landing. On the morning of 4 March, a 1 Squadron Hurricane shot down a Bf 109 over Germany and later, three other Hurricanes of the squadron attacked nine Messerschmitt Bf 110s north of Metz and shot one down. On 29 March, three Hurricanes of 1 Squadron were attacked by Bf 109s and Bf 110s over Bouzonville, a Bf 109 being shot down at Apach and a Bf 110 north-west of Bitche; a Hurricane pilot was killed trying to land at Brienne-le-Château.[34]

April – 9 May[edit]

Most Luftwaffe incursions in April were the usual reconnaissance flights but larger formations of fighters patrolled the front line and formations of up to three Luftwaffe squadrons (Staffeln) flew at high altitude as far as Nancy and Metz. Reconnaissance aircraft began to cross the front line in squadron strength to benefit from greater firepower on the most dangerous part of the journey, before dispersing towards their objectives. Hurricanes shot down a Bf 109 on 7 April at Ham-sous-Varsberg and on 9 April, when the Germans began the invasion of Denmark and Norway (Operation Weserübung), Bomber Command aircraft were diverted to operations in Scandinavia and the Battle squadrons took over leaflet raids over Germany by night; no aircraft were lost. The situation was unchanged until the night of 9/10 May, when the heavy artilleries of the German and French armies began reciprocally to bombard the Maginot and Siegfried lines.[35] In early May, the AASF had 416 aircraft; 256 light bombers, 110 of the 200 serviceable bombers being Battles.[36] The Armée de l'Air had fewer than a hundred bombers, 75 per cent of which were obsolescent. The Luftwaffe in the west had 3,530 operational aircraft, including about 1,300 bombers and 380 dive bombers.[37]

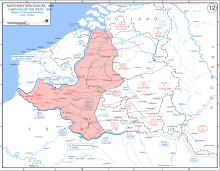

Battle of France (Fall Gelb)[edit]

10 May[edit]

As dawn broke, German bombers made a coordinated, hour-long attack on 72 airfields in the Netherlands, Belgium and France, inflicting severe losses on the Belgian Air Component (Belgische Luchtmacht/Force aérienne belge) and the Royal Netherlands Air Force (Koninklijke Luchtmacht).[38] The Luftwaffe bombers flew in formations of three to thirty Heinkel 111, Dornier 17 or Junkers 88s but had least effect on the British and French airfields, over which British and French fighters intercepted the German raiders.[39] Nine British-occupied bases were attacked to little effect. Hurricanes of 1 Squadron at Vassincourt patrolled the Maginot Line from 4:00 a.m. and shot down a He 111 for one Hurricane damaged. At 5:30 a.m. A Flight shot down a Do 17 near Dun-sur-Meuse for one Hurricane crash-landed.[40]

At Rouvres, two 73 Squadron Hurricanes attacked three bombers over the airfield, damaging one for a Hurricane forced down damaged. At 5:00 a.m. four Hurricanes attacked eleven Do 17s near the airfield, one Hurricane landing in flames with a badly burned pilot and one Hurricane returning damaged. More Hurricanes were scrambled and shot down two Do 17s; a He 111 was shot down soon afterwards. Orders to 73 Squadron led to it moving back from its forward airfield to its base in the AASF area around Reims. From England, 501 Squadron with Hurricanes, landed at Bétheniville to join the AASF and went into action within the hour against forty He 111 bombers.[41] A transport aircraft ferrying pilots and ground crews of the squadron crashed on landing; three pilots were killed and six injured.[42]

The AASF bomber squadrons remained on the ground waiting for orders but the bombing policy established by Grand Quartier Général (GQG, French supreme headquarters) did not require the British to obtain permission.[43] At Chauny, Barratt and d'Astier discussed reconnaissance reports and Barratt ordered the AASF into action. A German column had been reported in Luxembourg by a French reconnaissance aircraft several hours earlier.[41][e] The French bomber squadrons received orders and counter-orders; some were sent to make low-level demonstrations to reassure French troops and were intercepted by German fighters. The AASF squadrons had been on stand-by since 6:00 a.m., one flight in each squadron at thirty minutes' readiness and the other at two hours' notice. Barratt called General Alphonse Georges, commander of the Théâtre d’Opérations du Nord-Est (North-eastern Theatre of Operations) to tell him that the AASF would commence operations but it took until 12:20 p.m. to give the order to attack. Thirty-two Battles from 12, 103, 105, 142, 150, 218 and 226 squadrons flew at low altitude, in groups of two to four bombers, to attack German columns.[45]

The first wave of eight Battles had support from five 1 Squadron and three 73 Squadron Hurricanes, sent to patrol over Luxembourg City and clear away German fighters. The two fighter formations were not co-ordinated and had only vague orders; the three 73 Squadron Hurricanes attacked a force of unescorted German bombers and were bounced by German fighters before they made contact with the Battles. At least one Hurricane was shot down; the 1 Squadron pilots saw what was happening but were too low to help. The Battles hedge-hopped towards the target and evaded the German fighters but were well inside the range of German ground fire.[46] Two Battles of 12 Squadron attacked at 30 ft (9.1 m) and one was shot down as it approached the target. The second aircraft strafed the column with its forward firing machine-gun and bombed; neither side could miss and the Battle crash-landed in a field. Another twelve Battles were shot down and most of the rest were damaged.[46]

In the afternoon, a second raid by 32 Battles flying at 250 ft (76 m) was intercepted by Bf 109s and ten were shot down by fighters and ground fire.[45] During the day, AASF and Air Component Hurricanes claimed sixty Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, sixteen probables and twenty-two damaged. The AASF Hurricanes had flown 47 sorties and been provisionally credited with shooting down six bombers for five Hurricanes shot down or force-landed in a 1999 analysis by Cull et al.[47] No aircraft From Bomber Command in England appeared because the British state was preoccupied with a change in government. Barratt requested support and during the night, Bomber Command sent 36 Wellington bombers to attack Waalhaven and eight Whitleys from 77 and 102 squadrons bombed transport bottlenecks into the southern Netherlands at Geldern, Goch and Aldekirk; Rees and Wesel over the German border also being raided.[45]

11 May[edit]

As Blenheim crews of 114 Squadron at Vraux were preparing to take off to attack German tank columns in the Ardennes, nine Dornier 17s appeared at treetop height and bombed them, destroying several Blenheims, damaging others and causing casualties. From 9:30 to 10:00 a.m., eight Battles in two flights of two sections each from 88 and 218 squadrons took off to raid German troop concentrations near Prüm 10 mi (16 km) over the border in the Rhineland, where two panzer divisions had begun their westwards advance the day before and were already past Chabrehez, 20 mi (32 km) inside Belgium. From Reims, the Battles had to make a 60 mi (97 km) flight diagonally across the front. The raid was the first by 88 Squadron whose two sections flew 300 yd (270 m) apart to give the Germans no time to react. The Battles received constant small-arms fire at the vicinity of Neufchâteau, 50 mi (80 km) from Prüm, for the rest of the run in.[48]

An aircraft from the second flight force-landed near Bastogne, two more were lost near St Vith and the surviving aircraft had aviation fuel sloshing around the cockpit. The pilot turned back and attacked a column in a narrow valley at Udler, 15 mi (24 km) short of Prüm but the bomb-release gear had been damaged and they did not drop; the Battle managed to return and land at Vassincourt; the four Battles from 218 Squadron disappeared. An attack planned for the afternoon was cancelled because of the dusk and because Barratt wanted to conserve his aircraft.[49] The Belgian government appealed to the Allies to destroy the Albert Canal bridges around Maastricht but the Germans had already installed many anti-aircraft guns there. Six Belgian Battles out of nine from Aeltre were shot down around noon along with two of the six fighter escorts, the three survivors causing no damage.[50]

Six Blenheims from 21 Squadron and six from 110 Squadron in Britain attacked next from 3,000 ft (910 m). As the bombers approached they met massed anti-aircraft fire and broke formation to attack from different directions, only to spot Bf 109s and form up again. Four Blenheims were shot down, the rest were damaged and no bomb hit the target.[50] Ten modern French LeO 451s from GB I/12 and II/12, escorted by Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters, attempted the first French bombing raid of the battle and set fire to some German vehicles but failed to hit the bridges. The Morane pilots attacked the German fighters and claimed five Bf 109s for four Moranes; one LeO 451 was shot down and the rest so badly damaged that they were out of action for several days. During the night of 11/12 May, Barratt called on Bomber Command to attack transport targets around München-Gladbach; Whitleys from 51, 58, 77 and 102 squadrons, with Handley Page Hampdens from 44, 49, 50, 61 and 144 squadrons sent 36 bombers but five Hampdens returned early and only half the remainder claimed to have bombed the target. A Whitley and two Hampdens were shot down, the Hampden crews, minus a pilot, making their way back to Allied lines.[51] AASF, Air Component and 11 Group Hurricane pilots claimed 55 German aircraft and French fighter pilots in the RAF area claimed another 15; analysis by Cull et al. in 1999 attributed 34 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed or damaged to Hurricane pilots.[52]

12 May[edit]

At 7:00 a.m., nine Blenheims of 139 Squadron flew from Plivot to attack a German column near Tongeren but were intercepted by fifty Bf 109s and lost seven aircraft, two of the crews returning on foot after crash-landing. At Amifontaine, 12 Squadron was briefed for an attack on the bridges near Maastricht with six Battles. After the fate of the Belgian Battles the day before, the commander asked for volunteers and every pilot stepped forward; the six crews on standby were chosen. Two Blenheim squadrons were supposed to attack Maastricht at the same time as a diversion and twelve Hurricane squadrons were flying in support but half of these were operating to the north-west and the others were only flying in the vicinity, except for 1 Squadron, which was to sweep ahead to clear away German fighters.[53]

Three Battles of B Flight were to attack the bridge at Veldwezelt and three from A Flight the bridge at Vroenhoven. Two Battles of A Flight took off at 8:00 a.m. and climbed to 7,000 ft (2,100 m); 15 mi (24 km) short of Maastricht, the aircraft received anti-aircraft fire, surprising the crews with the extent of the German advance. The Hurricane pilots saw about 120 German fighters above them and attacked; three Bf 109s and six Hurricanes were shot down.[54] During the diversion, A Flight dived over the Maastricht−Tongeren road towards the Vroenhoven bridge covered by three Hurricanes; a Bf 109 closed on the leading aircraft, then veered off towards the second Battle, which hid in a cloud. The Battles dived from 6,000 ft (1,800 m) and bombed at 2,000 ft (610 m), both being hit in the engine, one Battle came down in a field, the crew being captured.[54] The second Battle crew, having shaken off the Bf 109, saw bombs from the first Battle explode on the bridge and hit the water and the side of the canal. The second Battle pilot turned away, amidst a web of tracer from ground fire and was then damaged by a Bf 109 fighter, which was hit by the rear gunner. The port fuel tank caught fire and the pilot ordered the crew to parachute, then he noticed that the fire had gone out. The pilot nursed the bomber home but ran out of fuel a few miles short and landed in a field; the observer got back to Amifontaine but the gunner was taken prisoner.[55]

Five minutes later, B Flight attacked the bridge at Veldwezelt, having flown over Belgium in line astern at 50 ft (15 m).[56] One Battle was hit and caught fire before the target, bombed and crashed near the canal; the pilot, despite severe burns, saving the crew who were taken prisoner. A second Battle was hit, zoomed while on fire, dived into the ground and exploded, killing the crew. The third Battle made a steep turn near the bridge then dived into it, destroying the west end. German engineers began immediately to build a pontoon bridge and as they worked, 24 Blenheims from 2 Group in England attacked the bridges at Maastricht; ten were shot down. At 1:00 p.m. 18 Breguet 693s from GA 18 with Morane 406 fighter escorts, attacked German tank columns in the area of Hasselt, St Trond, Liège and Maastricht, losing eight bombers. Twelve LeO 451s attacked columns around Tongeren, St Trond and Waremme at 6:30 p.m. and survived, despite most being damaged. Late in the afternoon, fifteen Battles flew against German troops near Bouillon and six were shot down. During the night, forty Blenheims of 2 Group flew in relays against the Maastricht bridges with few losses.[57]

At daybreak, the AASF intervened against the German advance towards Sedan for the first time, three Battles of 103 Squadron attacking a bridge over the Semois, the last river east of the Meuse. The Battles flew very low and all returned. At about 1:00 p.m. three more Battles of 103 Squadron attacked the bridge from 4,000 ft (1,200 m) and were intercepted by Bf 110s. The Battles dived and hedge hopped to evade the fighters, bombing a pontoon bridge next to the ruins of the original one from 20 ft (6.1 m) and escaped. At about 3:00 p.m. three Battles of 150 Squadron bombed German columns around Neufchâteau and Bertrix, east of Bouillon. One Battle was hit and crashed in flames but the other two bombed from 100 ft (30 m) and got away. At 5:00 p.m. three 103 Squadron Battles and three from 218 Squadron attacked in the vicinity of Bouillon, the Battles from 103 Squadron flew individually at low altitude and those of 218 Squadron flew in formation at 1,000 ft (300 m). General cover was provided by the Hurricanes of 73 Squadron but they claimed only a Henschel Hs 126 reconnaissance aircraft. Two 218 Squadron Battles were shot down and the low-level attack by 103 Squadron cost two more, the squadron having decided to dispense with the navigator for tactical operations by day.[58]

The surviving crew of 103 Squadron had also protected themselves by attacking a German tank column west of the target and running for home, according to the original AASF intention of attacking the first German troops encountered. Barratt had decided that the Battles should attack from a higher altitude to reduce losses from ground fire but Playfair took the view that the new policy would not put the Battles out of range of German anti-aircraft guns. The results of the operations on 12 May gave no conclusive evidence that low attacks were more dangerous. In the sixty sorties since 10 May the Battle squadrons had lost thirty aircraft and in the evening Barratt was ordered to conserve his force until the climax of the battle. In emergencies, the AASF was supposed to maintain a tempo of two-hourly attacks but this proved impossible; Playfair was ordered to rest the Battle squadrons on 13 May.[59] By the end of the day, the AASF had been reduced to 72 serviceable bombers.[60] AASF and Air Component Hurricanes were confronted by more Bf 109s over the front line, which shot down at least six of the twelve Hurricanes lost. The two Hurricane forces claimed 60 Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, probables or damaged, 27 being attributed to them in a 1999 analysis.[61]

13 May[edit]

Fifty miles north of the AASF bases, opposite the Meuse, the crisis of the battle of France was beginning but the Allied commanders still took the threat in the Low Countries more seriously. Four Battles of 76 Wing (12, 142 and 226 squadrons) received orders to attack German forces around Wageningen, about 250 mi (400 km) away but the raid was cancelled because of poor weather. Later on, seven Battles of 226 Squadron were sent to attack German columns near Breda, 200 mi (320 km) distant, despite the target being closer to 2 Group in England. No German columns were found; the Battles demolished a factory to block the road and returned safely. Information about the situation on the Meuse began to arrive and AASF HQ began to consider a contingency plan to evacuate to fields further south. During the evening a French pilot saw Germans crossing the Meuse at Dinant and landed at the closest airfield, which was that of 12 Squadron, quickly to attack the German crossing but Playfair and Barratt refused to allow it. Pressure on the British air commanders increased during the night when Billotte, the commander of Groupe d'armées 1 (1st Army Group), told Barratt and d'Astier that "victory or defeat hinges on the destruction of those bridges".[62]

The Germans had bridgeheads on the west bank of the Meuse and were building pontoon bridges to get tanks across; Barratt and d'Astier were told to make an immediate maximum effort. Unlike the permanent bridges attacked on 12 May, the German defences at Sedan were not organised, pontoon bridges were more vulnerable and the river was much closer to the AASF airfields, commensurately further from Luftwaffe bases.[63] French bombers made two attacks during the day and overnight the French bombed German rear areas as the Blenheims of 2 Group attacked the Maastricht bridges and railways at Aachen and Eindhoven.[62] Ten Hurricanes were lost on 13 May, six to German fighters for a claim of five Bf 109s and five Bf 110s, double the number eventually attributed to AASF and Air Component Hurricanes. Total claims were 37 German aircraft shot down, probables or damaged and 21 recognised in a 1999 analysis. The Hurricane squadrons in France lost 27 fighters shot down, 22 to German fighters, seventeen pilots being killed and five wounded. The Hurricane pilots claimed 83 German aircraft shot down, probables or damaged, later reduced to 46.[64]

14 May[edit]

At dawn, six Battles from 103 Squadron attacked the pontoon bridges over the Meuse at Gaulier north of Sedan; all of the Battles returned and some of the pontoons may have been damaged. At 7:00 a.m., four Battles attacked and returned safely. French apprehensions about the situation grew so intense that the Armée de l'Air decided to use obsolete Amiot 143 bombers and Barratt agreed to make a maximum effort. Hurricane squadrons from the north were to reinforce the AASF but still only to fly in the general area of the Battles, along with French fighters. After a second attack from the French-based bombers, 2 Group were to attack from England. At 9:00 a.m. eight Breguet 693s with fifteen Hurricane and fifteen Bloch 152 fighter escorts, attacked German tanks at Bazeilles and the pontoons between Douzy and Vrigne-sur-Meuse, against scattered anti-aircraft and fighter opposition; all the Breguets returned. Just after noon, eight LeO 451s and 13 Amiot 143s, also with fifteen Hurricane and fifteen Bloch 152 fighter escorts, attacked the same targets; three Amiots and a LeO were shot down. From 3:00 p.m. to 3:45 p.m. 45 Battles attacked the bridges and 18 Battles with eight Blenheims went for German columns. Some Battles flew higher, reducing the risk of hits by ground fire but became more vulnerable to fighters.[65]

Five Battles from 12 Squadron dive-bombed a crossroads at Givonne against intense small-arms fire; two managed to bomb but only one Battle returned. Eight Battles from 142 Squadron flew in pairs to attack pontoon bridges from low level, with bombs fuzed for an eleven-second delay. The pairs were intercepted by German fighters; four Battles were shot down, at least two by fighters. Six Battles of 226 Squadron tried to dive-bomb bridges at Douzy and Mouzon against ground fire. One aircraft was damaged and turned back; three more Battles were shot down. Seven of eleven 105 Squadron Battles were lost, one Battle landing at a nearby friendly airfield and another crash-landing. Four Battles of 150 Squadron were shot down by Bf 109s and eight from 103 Squadron bombed the Meuse crossings at very low altitude or in dives. Three of the Battles were hit but made it back to Allied areas before crash-landing, all but one pilot surviving and returning to base. Ten of eleven Battles from 218 Squadron were shot down and of the ten Battles from 88 Squadron, four against bridges and six to bomb columns between Bouillon and Givonne, nine returned. The operation was the costliest to the RAF of its kind in the war; 35 Battles and been lost from the 63 that attacked, along with five of the eight Blenheims. The survivors were too damaged to form a second wave. The afternoon attacks had met a much more effective defence than those in the morning and flying higher over German ground fire had only brought the Battles closer to German fighters. The German XIX Corps reported constant air attacks, which delayed the crossing of German tanks to the west bank of the Meuse.[66][f]

Every serviceable French bomber had flown and since 10 May, the Armeé de l'Air had lost 135 fighters, 21 bombers and 76 other aircraft.[67] Six Battle crews returned on foot through German-held territory but 102 aircrew had been killed or captured and more than 200 Hurricanes had been lost in four days. As night fell, 28 Blenheims of 2 Group attacked the bridges and seven were shot down, two coming down behind Allied lines. In Britain, Air Marshal Hugh Dowding, the Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command, was heard by the War Cabinet. Having already been ordered to send another 32 Hurricanes to France, Dowding urged that French requests for another ten fighter squadrons be refused.[68] The Air Staff took the losses as proof that tactical operations were not worth the cost, despite it working so well for the Luftwaffe and judged the Battle to be obsolete, despite the Blenheim, German Junkers Ju 87s and the new French Breguet 693 bombers suffering just as many losses when not escorted by fighters. Playfair and Barratt appealed for more fighters and got a few, despite calls from everywhere for more. Barratt demanded that no more Battles be sent to France without self-sealing tanks, until then the Battles would fly at night, except for crews with insufficient training in night operations or in dire emergency.[69][g] The AASF and Air Component Hurricane squadrons lost 27 aircraft, 22 to German fighters, 15 pilots being killed and four wounded; another two pilots had been killed and one wounded by German bombers or ground fire. The Hurricane squadrons claimed 83 German aircraft shot down, probables or damaged and a 1999 analysis attributed 46 German aircraft shot down or damaged to British fighters.[70]

15–16 May[edit]

After the AASF losses from 10 to 14 May, attacks on the Meuse bridgeheads on 15 may were made by Bomber Command squadrons based in England. German mobile forces broke out of the bridgehead at Sedan and at 11:00 a.m. twelve Blenheims from 2 Group attacked German columns around Dinant as 150 French fighters patrolled in relays. The RAF sent another sixteen Blenheims escorted by 27 French fighters at 3:00 p.m. to attack bridges near Samoy and German tanks at Monthermé and Mezières, from which four Blenheims were lost. On the night of 15/16 May around twenty Battles flew and attacked targets at Bouillon, Sedan and Monthermé for no loss but cloud cover made navigation and target finding difficult; fires were seen but no-one claimed great results. Night raids were suspended because Barratt expected the Germans to wheel south behind the Maginot Line and ordered the Battle squadrons to retire to bases around Troyes in southern Champagne, where during the Phoney War, the army and the RAF had prepared many airfields and several grass airstrips.[71]

Amid confusion caused by Luftwaffe attacks on the airfields and roads full of troops and refugees, the squadrons began to retire, many of the Battle squadrons being out of action during the moves, which turned out to be unnecessary when the Germans drove west instead of south. The AASF had been deemed a static unit, protected by the Maginot Line and was 600 lorries short of even its slender establishment of vehicles. The AASF was fortunate that the Germans went west and there was time to fetch most of the equipment, using 300 new lorries from the US, loaned by the French, at the behest of the Air Attaché in Paris. Drivers were rushed by air from Britain but were ignorant of the vehicles, the locations of AASF bases and of France; someone loaded the starting handles, jacks and tools onto a lorry bound for the west coast, under the impression that they were superfluous spare parts.[72] BAFF losses since 10 May stood at 86 Battles, 39 Blenheims, nine Westland Lysander army co-operation aircraft and 71 Hurricanes; Bomber Command had lost 43 aircraft, mainly from 2 Group.[73] The AASF and Air Component Hurricanes suffered 21 losses, half to Bf 110s and three to Bf 109s; five pilots were killed, two taken prisoner and four were wounded. The Hurricane pilots claimed fifty German aircraft, later reduced to 27 in a 1999 analysis by Cull, Lander and Weiss.[74] On 16 May, 103 Squadron moved south with full bomb loads to be ready as soon as they reached their new airfields but the squadron was not called on and the other squadrons seemed more intent on settling in, despite the disaster on the Meuse.[75]

17 May[edit]

The nine surviving Blenheims of 114 and 139 squadrons were transferred to the Air Component, reducing the AASF to six Battle and three Hurricane squadrons; for the next five days the AASF flew few missions, most of those at night.[76] The AASF withdrew 105 and 218 squadrons and their remaining aircraft, transferring crews to the other squadrons; 218 Squadron aircraft flying a few sorties before the change. The six squadrons sent away as much superfluous equipment as possible to become more mobile. In March, 98 Squadron had been based at Nantes as a reserve and sent crews and machines to the active squadrons; a shortage of gunners led to pilots substituting for gunners on occasion.[77]

Bomber Command sent twelve Blenheims of 82 Squadron, 2 Group, to attack German troops at Gembloux; ten were shot down by Bf 109s, an eleventh by ground fire and the twelfth Blenheim was damaged but returned to base.[78] As the French armies and the BEF in the north retreated, the most exposed Air Component squadrons were withdrawn westwards and land line communication with BAFF HQ, south of the German advance, was cut. No Hurricane pilots of the AASF and Air Component were killed but a minimum of 16 Hurricanes were shot down and one pilot taken prisoner. AASF, Air Component and 11 Group squadrons claimed 55 Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, probables or damaged, later reduced to 28 by Cull et al.[79]

18 May[edit]

On 18 May, the Battle squadrons were on stand-by but only 103 Squadron flew operations. Targets around St Quentin were bombed but low-level attacks were abandoned and with no escorts, the Battles flew in ones and twos, as fast as possible, trusting the manoeuvrability of the Battle rather than formation flying to evade fighters, despite being 100 mph (160 km/h) slower. The Battles flew at 8,000 ft (2,400 m) and attacked in a shallow dive, dropping bombs with instantaneous fuzes at 4,000 ft (1,200 m), all the Battles returning safely.[80] At least of 33 Hurricanes were shot down, most by German fighters. Seven pilots were killed, five made prisoners of war and four were wounded. Half of the Hurricane claims were against bombers and many Bf 110 fighters were shot down. The AASF and Air Component Hurricane squadrons claimed 97 German aircraft shot down, probables or damaged, later reduced by Cull et al. to 46.[81]

19 May[edit]

On 19 May the German advance in the north led to the Air Component squadrons retiring to English bases.[78] The AASF had 12, 88, 103, 142, 150, 218 and 226 squadrons available. D'Astier tried to support a counter-attack near Laon but the AASF HQ was out of touch and Barratt knew nothing about it, except that German forces were west of the Montcornet–Neufchâtel road. Reconnaissance reports showed Barrett that to the east, more German troops were north of Rethel, a threat to the AASF bases further south. All but 226 Squadron was ordered make another maximum effort by day against anything they saw on the roads between Rethel and Montcornet. The wrong orders reached 88 Squadron which attacked around Hirson an important point on the German drive west and 142 Squadron attacked targets far to the west around Laon, near the French counter-attack, unlike the Rethel area, which was on the fringe of the offensive and only occupied by screening forces. Six Battles of 150 Squadron attacked road columns near Fraillicourt and Chappes, against intense anti-aircraft fire, one Battle being shot down and two making emergency landings at the nearest Allied airfield.[82]

The crews of 218 Squadron bombed tanks and lorries near Hauteville and Château-Porcien, in shallow dives from 7,000 to 6,000 ft (2,100 to 1,800 m), bombing from 4,000 to 2,000 ft (1,220 to 610 m). Plenty of targets were found by 88 Squadron, which with 218 Squadron, lost no aircraft. Three Battles from 142 Squadron were shot down west of Laon and of six Battles sent by 12 Squadron north or Rethel, which found only one column to bomb, two were lost, one to a Bf 109. Six Battles sent by 103 Squadron bombed targets near Rethel and all came home. The raids did nothing to assist the French counter-attack. The Germans had passed beyond the terrain bottlenecks further east. Six Battles out of 36 had been lost, an 18 per cent loss rate, which was a considerable improvement on the 50 per cent rate from 10 to 15 May but still unsustainable. Barratt concluded that night operations were the only way to save the Battle force from destruction.[83] AASF and Air Component Hurricanes claimed 112 Luftwaffe aircraft shot down, probables or damaged (later reduced to 56) for a loss of 22 Hurricanes shot down and 13 force-landed, 24 to Bf 109s, which suffered 14 losses to the Hurricanes. Eight fighter pilots were killed, seven were wounded and three taken prisoner.[84]

20–21 May[edit]

On 20 May, 73 Squadron flew one patrol, 1 Squadron and 501 Squadron being rested and no claims or losses were recorded for the AASF Hurricanes. The commander of 1 Squadron asked for the relief of tired pilots and eight were immediately dispatched, three arriving the same day. Twelve Hurricanes were shot down, at least seven by ground fire while strafing, three pilots being killed and one captured. AASF and Air Component pilots claimed forty aircraft shot down, probables or damaged, reduced by Cull et al. to 18.[85] During the night of 20/21 May, 38 Battles were sent to bomb communications around Givet, Dinant, Fumay, Monthermé and Charleville-Mézières. Misty conditions around the Meuse led to few of the Battle pilots claiming hits on anything and one aircraft was lost.[86]

Delays caused to the German advance in these areas could have no effect on the beginning of the Battle of Arras 100 mi (160 km) to the west.[86] On 21 May the AASF and Air Component Hurricanes claimed four German aircraft, three of which were recognised by Cull et al. for the loss of three Hurricanes, one pilot killed, one taken prisoner and one returned unhurt.[87] The AASF bombers resumed daylight operations and 33 Battles, in small flights, attacked German columns near Reims, indirectly supported by 26 Hurricanes in the area. Attacks near Le Cateau and St Quentin could have been on French troops by mistake; poor air reconnaissance made it difficult to find German forces or their objectives.[88][h]

21–22 May[edit]

By 21 May only some Lysanders of 4 Squadron, attached to the BEF HQ, were all that remained of the Air Component in France.[89] The pilots of the three AASF Hurricane squadrons were exhausted; most of those of 1 Squadron were replaced and 73 Squadron pilots were given notice of their replacement; the 501 Squadron pilots, having been in France only since 10 May, had to remain.[90] Hurricane reconnaissance sorties discovered the German advance from Cambrai on Arras and the ground control organisation at Merville ordered the Hurricanes that were airborne to strafe them. When fighter squadrons on escort or fighter patrol turned for home, they began to use up their ammunition on ground targets. The fighters still attacked in tight formations and in fifty ground strafing sorties by the various British fighter forces in France, six Hurricanes were shot down and three pilots killed.[91] With another French counter-attack due on 22 May, the British government demanded a greater effort from the RAF and during the night of 21/22 May, 41 Battles were prepared for raids on the Ardennes.[86]

After 12 Battles had taken off, the Air Ministry cancelled the operation in favour of operations against German tanks the next day around Amiens, Arras and Abbeville, contrary to Barratt's better judgement since tanks were small targets and the Battles would have to attack at low altitude.[86] The patrol area was too far west to assist a French counter-attack south from Douai on Cambrai but might have had an effect on operations on the right flank of the BEF. The weather remained poor and after several aircraft took off, the raid was cancelled. Tanks were seen around Doullens, Amiens and Bapaume and one was claimed for the loss of one Battle and three damaged.[92] Night operations by the AASF Battles against the Meuse crossings had suffered few losses but their training in night flying during the spring could not overcome the inherent difficulty of night navigation and target-finding.[93] During the night of 22/23 May, 103 Squadron was sent to bomb Trier on the German–Luxembourg border.[94][i]

23 May[edit]

Uncertainty about supporting an Allied attack south or a retreat north, led to a dawn attack by the Battles of 88 Squadron around Douai and Arras being cancelled. To prevent an Allied retreat to Dunkirk being cut off, bombing of German forces to the north-west of Arras was substituted. The new raid was cancelled too and 88 Squadron flew no operations. In the evening, 12 Squadron sent four Battles against German tanks on the Arras–Doullens road but the weather deteriorated and only two of the bombers found the target; all four aircraft returned. Four Battles from 150 Squadron made dive-bombing attacks on German tanks at the exit of the village of Ransart and vehicles in a stand of trees further south. One pilot dropped his bombs then strafed another column that appeared, despite considerable anti-aircraft fire; the four Battles survived despite all being met with ground fire. During the night of 23/24 May, 37 Battles bombed targets at Monthermé and Fumay.[96] Hurricane squadrons of the AASF and Fighter Command engaged Bf 109s in northern France, claiming six fighters for the loss of ten Hurricanes.[97]

24 May[edit]

No Battle sorties were flown in daylight on 24 May but 73 Squadron Hurricanes from Gaye, near Paris, claimed one Luftwaffe aircraft for the loss of two aircraft and one pilot severely burned.[97] During the night of 24/25 May 41 Battles attacked railway sidings at Libramont, supply dumps at Florenville and the roads through Sedan, Fumay, Givet and Dinant with 20 lb (9.1 kg) incendiary, 40 lb (18 kg) anti-personnel and the usual 250 lb (110 kg) bombs. AASF night sorties equalled the number flown by the Armée de l'Air but the Battles were not built for night operations, despite night flying training; the limited view from the observer compartment left the occupant unable to help with target finding. Long-range night sorties were extremely difficult and attacks on the Meuse crossings from the AASF bases around Troyes required a 100 mi (160 km) cross-country flight. The Allied retreats towards the Channel and North Sea coasts had multiplied the number of supply routes open to the German armies, making attacks on the Meuse crossings less effective.[96]

25 May[edit]

During the night of 24/25 May, Frankfurt, 100 mi (160 km) over the German border, was attacked by 88 Squadron, a 250 mi (400 km)-flight of dubious relevance to the fighting in France and Belgium. During the day, about ten Battles from various squadrons attacked German columns on the Abbeville–Hesdin road for the loss of one aircraft, the crew managing to return on foot.[98] A Do. 17 was claimed by 73 Squadron for the loss of a Hurricane and the capture of the pilot.[99] The code-breakers at Bletchley Park in Britain decrypted a Luftwaffe signal received at 1:30 p.m., that revealed a conference of Luftwaffe commanders to be held on the next day at the HQ of Fliegerkorps VIII at 9:00 a.m. in Roumont Château, near Libramont in southern Belgium. The commanders were to arrive at Ochamps airfield nearby, at 8:30 a.m. The Air Ministry received the information in the early hours of 25/26 May and signalled the news to the AASF HQ at 2:40 a.m., sending more intelligence at 5:15 a.m.[100]

26 May[edit]

Playfair passed orders to attack the château to 103, 142 and 150 squadrons at 7:30 a.m. At 9:00 a.m. fourteen Battles set off for the target supported by Hurricanes of 1 and 73 squadrons. The Battles flew in pairs and the leader of the two aircraft from 150 Squadron lost touch with the other Battle after flying into a storm and descending to 5,000 ft (1,500 m). The crew eventually found the château, dive-bombed from 3,000 ft (910 m) and were attacked by four Bf 110s. The pilot tried to hedge hop out of danger and as the Bf 110s gave chase, the pilot fired at a German aircraft he had spotted landing on an airstrip ahead. The Battle was hit on the armour fitted to resist fighter attack and the robust structure of the airframe protected the crew; the pilot only had to force-land after the engine was hit. The pilot escaped but the navigator and gunner were taken prisoner. Most of the rest of the Battles found the target through the stormy weather and damaged the building but inflicted no casualties; a second Battle was lost. No more operations in daylight took place until 28 May.[101]

27–31 May[edit]

The Battles were grounded by bad weather on the night of 26/27 May but thirty-six Battles attacked German targets on the night of 27/28 May and a fire was reported after bombing near Florenville in Belgium. The weather grounded most of the Battles on the nights of 28/29, 29/30 and 30/31 May.[102][j] On 28 May, the AASF Battles began attacks to obstruct the massing of German forces on the Somme and Aisne rivers and the bridgeheads that the Germans had established over the Somme. The Battles used '40 lb' (17.5 kg) General Purpose bombs during the day for the first time, which could be dropped from lower altitudes and were better suited to hit dispersed troops and vehicles. Six Battles from 226 Squadron attempted to dive-bomb targets around Laon but failed because of low cloud; three tried to bomb targets through gaps in the clouds and three returned with their loads.[103]

Six more 226 Squadron Battles were later sent to bomb roads into Amiens and Péronne; one Battle returned early after a window panel blew out and the others used steep or shallow dive-bombing attacks against German troops and transport. After bombing, the pilots used their forward-firing guns to strafe every German column they saw, one pilot taking five minutes to exhaust his ammunition; a Battle received damage but all returned. Day sorties were also flown by 103 Squadron on the roads into Abbeville, one Battle being severely damaged. Since 14 May the Battles had flown about 100 sorties by day for a loss of nine aircraft, a considerable reduction in the rate of loss, despite the lack of self-sealing fuel tanks, un-armoured engines and no close fighter escorts. The weather prevented night sorties on 26/27 May but on the night of 27/28 May, 36 Battles flew and fires were reported in Florenville; no other effect being reported by the crews. Few sorties were flown on the nights of 28/29, 29/30 and 30/31 May because of bad weather. Since 10 May, the AASF had lost more than 119 aircrew killed and 100 Battles.[104]

Fall Rot[edit]

1–4 June[edit]

Operations in May proved the French right about the lack of fighters in the AASF. Fighter sweeps and patrols in the general area of Battle operations had proved futile and Barratt judged that day bombers needed close escort by fighters if they were to survive. From 20 May, Blenheims flying from Britain had received fighter escorts and losses were drastically reduced; the AASF Battles needed similar protection, which needed more than the three Hurricane squadrons in the AASF could provide. Barratt informed the Air Ministry that either the fighters should be reinforced or the bombers returned to Britain. Given the desperate situation in France, returning the AASF was unthinkable; Barrett said that fighter reinforcements were needed immediately, not as a panic measure once the German offensive resumed. The British government and the Air Staff refused to weaken British air defences and not even the AASF fighter losses were replaced. Barrett decided to limit daylight Battle sorties to the number that the Hurricanes could escort and keep the rest on night raids. The build-up in the bridgeheads over the Somme at Péronne, Amiens and Abbeville continued, making German intentions obvious.[105]

The AASF bombers were used to interrupt the German preparations on the night of 31 May/1 June but some Battles were sent to attack the Rhine bridges near Mainz, about 100 mi (160 km) east of the Meuse; military traffic over the Rhine could have no influence on the battle soon to begin. The night bombing operations were also disrupted by the move of the Battle squadrons from their airfields around Troyes to Tours, 150 mi (240 km) west of Paris, 200 mi (320 km) from the nearest German forces and 300 mi (480 km) from targets in the Ardennes. The Battles of 12 Squadron moved from Échemines to Sougé then had to use Échemines as an advanced base. During the move, 103 Squadron and 150 Squadron flew several sorties against targets in the Ardennes and Germany. On the night of 3/4 June, 12 Squadron made five sorties to attack rail lines near Trier. On 4 June, the Battle squadrons were stood down for maintenance and to "settle in"; Fall Rot (the German offensive) began the next day.[106]

5 June[edit]

The German offensive over the Somme and Aisne rivers began with attacks from the three Somme bridgeheads but made only slow progress. The AASF had only 18 operational Hurricanes, which were used to protect Rouen, not the Battles, which had not flown in daylight since 28 May. With the French sending every aircraft that could fly, Barratt returned the Battles to day operations. At 7:30 p.m. eleven Battles of 12 and 150 squadrons flew to Échemines and then attacked German columns on the Péronne–Roye and Amiens–Montdidier roads, although many crews failed to find targets and some mistakenly attacked French tanks near Tricot, 25 mi (40 km) behind the French front line; when French fighters arrived, the Battles flew away. The AASF used Échemines and other airfields as advanced bases for day and night operations, despite complaints that their facilities were inadequate and that Échemines had recently been in use as a main base. The German armies managed to enlarge the Somme bridgeheads by nightfall and during the night, Battles attacked the airfield near Guise but eleven were sent to attack targets in the Ardennes, which was of no help to the French armies.[107]

6 June[edit]

The three AASF fighter squadrons were brought up to strength, although this was still inadequate; a deputation from the 51st (Highland) Division even went to BAFF HQ to demand more protection. Nine Battles escorted by a flight of 73 Squadron Hurricanes flew from Échemines at 4:30 p.m. against German columns on the Ham–Péronne road and others bombed tanks and vehicles between Péronne and Roye. Bf 109s got past the Hurricanes and attacked two Battles, which survived. Raids that night were made closer to the front line, where they might have immediate effect and the pilots flew lower. After the first take-off attempt at 11:45 p.m. and a second try at 1:15 a.m. were interrupted by German air raids, Battles from Harbouville attacked a Somme bridge north of Abbeville, roads out of the town and roads out of Amiens. As the Battles returned, several were damaged by another German raid. At Échemines, twelve Battles set forth to bomb airfields and other targets near Laon, Guise ad St Quentin, one pilot claiming hits on a fuel dump.[108]

7 June[edit]

The French defence of the Abbeville bridgehead began to collapse and 22 Battles attacked German columns between the Abbeville–Blangy-sur-Bresle road and Poix. The aircraft bombed from 2,000 to 3,000 ft (610 to 910 m) to evade ground fire, despite having an escort of only a flight of 73 Squadron Hurricanes, the escorts flying close to the bombers. When escorted, the Battles flew to the target in formation, attacked singly then ran for home. When there were no escorts, the Battles flew alone or in pairs, relying on their manoeuvrability to escape from fighters, their targets being close enough to the front line to give them a chance of escaping; several Battles survived fighter attacks but three were shot down. In the first three days of Fall Rot the Battles flew 42 day sorties for a loss of three aircraft, despite their lack of self-sealing fuel tanks, armour against ground fire and the small number of escorts. The reduction in losses was marked but 17 French day bomber groups had managed to fly 300 sorties over the same period; Barrett remained reluctant to risk more Battles in daylight.[109]

8 June[edit]

As the French armies resisted the German offensive from the Somme bridgeheads, reconnaissance aircraft returned with evidence of an imminent German attack over the Aisne, to the east of Paris. During the night of 7/8 June, eight Battles attacked the Laon–Soissons road after German tanks were reported there. The battle at the Somme bridgeheads retained its priority because the French defences north of Amiens began to collapse (Poix having been lost on the evening of 7 June). The AASF fighters was reinforced by 17 Squadron and 242 Squadron from England. At 1:30 p.m. twelve Battles attacked German columns in the area of Abbeville, Longpré, Poix and Aumale, escorted by seven Hurricanes; three Battles were shot down. At 3:30 p.m. another eleven Battles attacked, despite the Hurricane escorts not arriving; the pilots reported that German tank and lorry columns were 5 mi (8.0 km) long and one Battle was lost. As one pilot returned, he saw a formation of Ju 87s, dived through and damaged one Stuka with his forward-firing gun, before the Bf 109 escorts intervened. The Battle gunner was wounded but claimed a Bf 109 and the pilot made an emergency landing south of Paris; another Battle pilot engaged a Junkers Ju 88 bomber.[110]

9 June[edit]

During the night of 8/9 June, several Battles bombed the Somme river crossings at Amiens and Abbeville and seven sorties were flown against the forests around Laon, north of the Aisne, where German troops were thought to be hiding. During the day, an attack on German tank, artillery and troop columns near Argueil was planned but the diversion of the Hurricanes to protect the 51st (Highland) Division led to the operation being cancelled. The expected German offensive over the Aisne began against determined French resistance but on the Channel coast the Germans had broken through. During the night of 9/10 June, ten Battles were sent to bomb bridges and roads at Abbeville and Amiens; nine more, using the staging post of Échemines airfield, attacked targets around Laon, dropping incendiary bombs on Forêt de Saint-Gobain to the north-west, to flush out German troops thought to be using it for cover; lorries driving south with their lights on were also attacked.[111]

10 June[edit]

In the afternoon, twelve Battles attacked German units close to Vernon on the Seine, about half-way between Paris and Rouen; one Battle being shot down and another damaged, thought to have been hit by a Hurricane. Later, twelve Battles attacked German motorised columns near Vernon, the Seine bridge at Pont Saint-Pierre and a bridge further south. Despite all of the Hurricanes being sent to cover the evacuation from Le Havre, no Battles were lost. Fifteen Battles returned to the targets after dark and seven were sent to attack the Meuse crossings.[111]

11 June[edit]

The speed of the German advance made the use of forward airfields like Échemies as staging posts redundant and at dawn, twelve Battles bombed crossings over the Seine to the south of Les Andelys. Around noon, six Battles with fighter escort bombed more bridges in the area and in the afternoon sixteen escorted Battles made similar attacks. After a request from the French naval commander of Le Havre to attack tanks thought to be close to the port, six Battles with escorts tried to attack the tanks but found only a couple of armoured vehicles and attacked them. It turned out that the tanks had reached the coast and turned north to cut off the French IX Corps and the 51st (Highland) Division. The Battles had managed a minimum of 38 sorties for a loss of two or three aircraft. Another 24 Battles were to continue the attacks downstream of Rouen that night but only five took off due to inclement weather.[112]

12 June[edit]

At dawn, nine Battles bombed the roads around Les Andelys, north of the Seine, for no loss. In the afternoon, twelve Battles bombed a concentration of vehicles blocked at the Pont de l'Arche railway bridge south of Le Manoir, forcing German engineers repairing it to flee for cover, also for no loss. An attack on pontoon bridges south of Les Andelys was thought to have failed in poor visibility, for one Battle lost and one damaged. Fifteen Battles were sent out to the roads around Les Andelys that night but only seven reached the target in more poor weather.[113]

13 June[edit]

At dawn six battles flew an armed reconnaissance around Vernon and Évreux, again in poor weather, which made it impossible for fighters to escort the Battles, difficult for the crews to see targets and for German fighters to intercept them; there were no losses. Later operations by 150 and 142 squadrons flew in such bad weather that two of the seven Battles turned back. No fighters were able to escort the Battles but four were shot down by Bf 109s. During the afternoon, the French armies east of Paris tried to retreat from the Aisne to the Marne but two armies diverged and German armoured columns rushed through the gap, overtaking some of the retreating French troops past Montmirail towards the Seine. At 3:00 p.m. twelve Battles attacked German columns south of the town and lost one Battle. So many German tanks and vehicles were seen that a maximum effort was made by 26 Battles without fighter escort, except for some French fighters which were busy protecting French bombers. The British bombers were attacked by German fighters and by massed anti-aircraft fire; six Battles were shot down, four by fighters. Paris was declared an open city and with the end of hostilities likely, preparations to evacuate the AASF continued as the Battle squadrons fought on without fighter escorts.[114]

14–26 June[edit]

Fighter operations were still hampered by bad weather and escorting the Battles was made more difficult by a disorganised retirement of the fighter squadrons to other airfields. Ten Battles tried to attack German columns near Évreux but could not find them in the bad weather. Two Battles reconnoitring near Paris spotted two Bf 109s on Le Coudray airfield, south of Paris, which had just been evacuated. During the afternoon, nine Battles attacked woods around Évreux and the airfield, two of the three bombers from 12 Squadron being shot down. Orders arrived from Britain during the evening for the Battle squadrons to return and the AASF bombers prepared to make a final attack at dawn. Ten Battles of 150 Squadron, with Hurricane escorts, took off to attack targets around Évreux again, then landed at Nantes, the first stage of their departure from France; the other squadrons managed twelve sorties and took the same route back; about sixty Battles returning to Britain.[115] The remaining AASF Hurricanes began operations to cover evacuations from ports on the French Atlantic coast. Nantes, Brest and St Nazaire were defended by 1, 73 and 242 squadrons, St Malo and Cherbourg by 17 and 501 squadrons flying from Dinard in Brittany and later the Channel Islands. On 18 June, 1 and 73 squadrons, the first to France in 1939, were the last to leave, although many unserviceable Hurricanes and those without fuel were abandoned, not all of them being destroyed.[116] AASF headquarters was disbanded on 26 June 1940.[117]

Aftermath[edit]

Analysis[edit]

Fighters[edit]

| Claims | 1 Sqn |

73 Sqn |

501 Sqn |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | 63 | 33 | 32 | 128 |

| Probable | 11 | 7 | 1 | 19 |

| Losses | ||||

| Hurricanes | 21 | 15 | 6 | 42 |

| Killed | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| PoW | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Wounded | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

Flying Officer Paul Richey of 1 Squadron told a staff officer from AASF HQ that

We're operating in penny packets and are always hopelessly inferior in numbers to the formations we meet. My humble opinion is that we should not operate in formations less than two squadrons strong on bomber cover.[120]

and in 1999, Cull et al. wrote that Hurricane tactics in France were inept, the fighters being sent into action in threes or sixes against far larger Luftwaffe formations. Fighter pilots had been trained to attack bombers over England, beyond the range of German single-engined fighter escorts and formation flying received more emphasis than observation, dog-fighting and gunnery.[121]

Experience gained during the Phoney War was not generally applied; some Hurricane pilots enjoyed great success but the Hurricane squadrons suffered needless casualties for lack of training and leadership. The use of tight formations meant that Hurricane pilots seldom saw the aircraft that shot them down. Few squadron commanders flew on operations and some were flagrantly incompetent.[120] Flying from improvised and unprotected airstrips, rather than the airfields enjoyed by the Fighter Command squadrons in Britain, reduced the number of serviceable aircraft. Most Hurricane engagements took place against bombers, reconnaissance aircraft and the twin-engined Bf 110 heavy fighter, inferior in manoeuvrability but present in much greater numbers. The Hurricanes made bomber escorts necessary but suffered disproportionate losses when they met Luftwaffe Bf 109s which used stalking tactics, attacking unseen out of the sun rather than dog-fighting.[121]

Bombers[edit]

According to Greg Baughen (2016) on 10 May, the Fairey Battle had been a disaster as a tactical bomber; when flying high, they were shot down by fighters and when low, by anti-aircraft fire. With fuel for a range of 1,000 mi (1,600 km) in un-armoured and non-self-sealing tanks, carrying a navigator in a cabin with a poor view outside, the Battle was highly unsuitable for short-range, low altitude, tactical attacks. Extra armour and self-sealing fuel tanks had been delivered to France but not fitted.[122] The crews lacked experience and at first may have taken too long to bomb, sometimes attacking over flat ground, which gave a good view of the target and an equally good view of the aircraft from the ground. With more experience, pilots used ground features for cover and made shorter approach runs.[123] The German invasion demonstrated that RAF crews were not sufficiently equipped or trained for daylight tactical operations and army support; during the Battle of Arras (21 May) the BEF had received no air cover.[124]

The attacks on 14 May were catastrophic and the Air Staff claimed that the losses suffered by the AASF showed that tactical air support was not a feasible operation of war. The ministry claimed that the Battle was obsolete, rather than in need of more armour, self-sealing tanks, guns and fighter support. After the war, German officers said that day bombing caused them many delays and that they had not noticed the British night bombing offensive against the Ruhr. The AASF had made a start on becoming a flexible tactical air force; daylight operations by the Battles had more effect on the German offensive than Wellington bombers flying by night.[124] Sending low-performance aircraft over the battlefield might seem suicidal but slow biplanes like Dutch Fokker C.X bombers, the German Henschel Hs 123 dive-bomber and close support aircraft and British Hawker Hector army co-operation aircraft had been used in 1940 for ground attacks at low altitude. Against the ragged forward edge of advanced forces, with ill-organised anti-aircraft defences, such slow, light and highly-manoeuvrable aircraft could hit targets and escape.[125]

Command[edit]