George Whyte-Melville

George John Whyte-Melville | |

|---|---|

Caricature by James Tissot in Vanity Fair | |

| Born | 19 June 1821 Mount Melville, St. Andrews, Scotland |

| Died | 5 December 1878 (aged 57) Braydon Pond, Charlton, Wiltshire, England |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation(s) | Sportsman, soldier, and author |

| Years active | 1851–1878 |

| Known for | Novels with a hunting setting |

| Notable work | Riding Recollections (1878) |

George John Whyte-Melville (19 June 1821 – 5 December 1878) was a Scottish novelist much concerned with field sports, and also a poet.[1][2] He took a break in the mid-1850s to serve as an officer of Turkish irregular cavalry in the Crimean War.

Life and work[edit]

George John Whyte-Melville was born in 1821, at Mount Melville near St Andrews, Scotland, as a son of Major John Whyte-Melville and Lady Catherine Anne Sarah Osborne and a grandson on his mother's side of the 5th Duke of Leeds.[3] His father was a well-known sportsman and Captain of The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews.

George was tutored privately at home by the young Robert Lee,[4] then educated at Eton, before entering the army with a commission in the 93rd Highlanders in 1839.[3][5] He exchanged into the Coldstream Guards in 1846,[6]: xiii and retired with the rank of captain in 1849.[3][note 1]

Whyte-Melville married the Hon. Charlotte Hanbury-Bateman in 1847,[3] and they had one daughter, Florence Elizabeth, who went on to marry Clotworthy Skeffington, 11th Viscount Massereene. His marriage was not a happy one,[6]: xv and this led to the "constantly recurring note of melancholy" that runs through all of his novels, "especially in reference to women".[6]: xiv His wife also was not happy with the marriage. [5] [note 2]

In 1849 Whyte-Melville was the subject of a summons for maintenance by Elizabeth Gibbs, described as "a smartly-dressed and interesting looking young woman", who alleged that he was the father of her son. She stated that she had known Whyte-Melville since December 1846 and that she had given birth to his child on 15 September 1847. The Magistrate read some letters stated by Gibbs to be from Whyte-Melville, in one of which the writer expressed his wish that Gibbs would fix the paternity unto some other person as he did not wish to pay for the pleasure of others.[9] The Magistrate found for the defendant as the written evidence could not be proved to be in Whyte-Melville's hand, but allowed the complainant to apply for a further summons in order to obtain proof.[9] Gibbs testified that since the child was born, she had received £10 from Whyte-Melville, and he had offered her two sums of £5, on condition that she surrender his letters to her, and sign a disclaimer on further claims.[10] The case continued on 25 September 1849. Gibbs' landlady, supported by her servant, testified that Gibbs was in the habit at the time of receiving visits from other gentlemen, particularly two, one of whom had paid for the nurse and supported Gibbs during her confinement. The magistrate said that there had definitely been perjury on one side or the other and dismissed the summons.[11]

After translating some Horace in 1850, Whyte-Melville published his first novel, Digby Grand, in 1852, which was a success. He went on to publish 21 other novels and became a popular writer about hunting. Most of his heroes and heroines – Digby Grand, Tilbury Nogo, the Honourable Crasher, Mr Sawyer, Kate Coventry, Mrs Lascelles – ride to hounds, or are would-be members of the hunt. Some characters reappear in different novels, such as the supercilious stud groom, the dark and wary steeple-chaser, or the fascinating sporting widow.[12]

Bones and I, or The Skeleton at Home, is an anomaly in his work, as it is far from the realms of the hunting field or historical romance. It centres on an urban recluse living in a small, modern villa in a London cul de sac, looking out on "the dead wall at the back of an hospital". His most famous lyric is also unusual in its unexpected melancholy – the words to Paolo Tosti's song "Good-bye!" Several of his novels are historical, The Gladiators being the best known. Whyte-Melville also wrote Sarchedon, a historical novel set in Ancient Babylon.[13] He also published volumes of poetry, including Songs and Verses (1869) and Legend of the True Cross (1873). However, it is for his portrayal of contemporary sporting society that he is most regarded.

Henry Hawley Smart is said to have taken Whyte-Melville as one of his models when he too set out to be a sporting novelist.[14] Mrs. Lovett Cameron (1844–1921) acknowledged that her novel A Grass Country was inspired by Whyte-Melville.[15]: 102 He also served as one of the two models for the writing of Mrs. Robert Jocelyn.[15]: 336 He was the first person to encourage Florence Montgomery (1843–1923) to publish her children's stories,[8]: 282 and persuaded her to do so.[15]: 443 The novelist John Galsworthy admired the "bright things" in Whyte-Melville's novels, and wrote that Digby Grand was Jolyon Forsyte's first idol (in the Forsyte Saga).[16]

The catch phrase for which he is best remembered comes from a song about hunting: "Drink, Puppy, Drink". This recurs also in The Flashman Papers by George MacDonald Fraser, as a frequently mentioned favourite song of the anti-hero. In 1876, Whyte-Melville penned the rarely attributed, but widely recognized opening line to the short poem The Object of a Life: "To eat, drink, and be merry, because to-morrow we die."[17]

Crimean War[edit]

When the Crimean War broke out, Whyte-Melville went out as a volunteer major into the Turkish irregular cavalry,[3] but this was the only break in his literary career.[12]

Death[edit]

Whyte-Melville lost his life in 1878 while hunting with the Vale of White Horse Hunt, falling as he galloped over a ploughed field at Bradon Pond, Charlton, Wiltshire.[18][19][5] The Dublin Evening Mail said that it was "strange that he, so gallant and accomplished a horseman, who had dared danger with a light heart so often, should have perished, not while jumping a difficult fence, but simply while galloping across a ploughed field."[20] He, a skilled horseman, had often boasted that he had only fallen once in the twenty years from 1847 to 1867.[21]

He had moved to Tetbury, Gloucestershire, in about 1875, the better to follow the Beaufort and Vale of White Horse hunts. George Whyte-Melville was buried in the churchyard of St Mary's, Tetbury, within a few feet of his property, Barton Abbotts. When he rented the house, a friend criticised the choice because it was so near the graveyard. Whyte-Melville replied that perhaps it was, but that it was a good choice for a hunting man, as his friends would not have to carry him far.[6]: xviii His estate was valued at under £70,000.[18]

Memorials[edit]

It has been claimed that Whyte-Melville's death inspired the well-known hunting song "John Peel" – although John Peel was a real-life huntsman in the Lake District, the author of the lyrics, John Woodcock Graves, was a close friend of Whyte-Melville. After imbibing a quantity of alcohol at Whyte-Melville's funeral, Graves penned some verses in tribute to Whyte-Melville, set to the melody of a traditional folk song entitled, "Bonnie Annie".[citation needed]

The Scottish Border poet and Australian bush balladeer Will H. Ogilvie (1869–1963) was strongly influenced by Whyte-Melville, so much so that he addressed two poems to him. These lines are from the Scattered Scarlet anthology of 1923:

- How good it is, how good, to fling aside

- The last new garbage-novel of the day

- And turn again with pleasure and with pride

- To your long line of volumes silver-grey,

- And with you, gallant heart, to ride away

- Through that clean world where your Sir Galahads ride!

At the instigation of Whyte-Melville's mother, Lady Catherine Melville, a memorial fountain to him was erected by public subscription in Market Street, St Andrews, Fife, in 1880.[22] The three-tier cascading fountain is about 14 foot (427 cm) high, composed of sandstone and Dalbeattie granite. It features four marble plaques dedicated to Whyte-Melville, which show his bust, the family coat of arms, the arms of the Coldstream Guards, and a memorial inscription.[23] Due to corrosion of its internal pipes, it fell into disuse – possibly in the 1930s[24] – and was treated as a flower bed for many decades. A local councillor and the St Andrews Merchants' Association led a campaign that ended in its resuming function as a fountain on Wednesday 8 July 2015.[25]

The novelist Rosemary Sutcliff said in her memoir Blue Remembered Hills (1983)[26] that her first complete (and unpublished) novel Wild Sunrise was 'as Victorian-English as anything in Whyte-Melville's The Gladiators'. This early work went on to be reworked as her award-winning The Eagle of the Ninth (1954), on which she based her highly successful writing career.

Books by Whyte-Melville[edit]

The list is based on the "complete list of Whyte-Melville's writings" presented in the 1898 edition of "Riding Recollections".[6]: xix

- Digby Grand (1852)[27]

- General Bounce (1854)[28]

- Kate Coventry (1856)

- The Interpreter (1858)[note 3]

- Holmby House (1860)

- Good for Nothing (1861)

- Market Harborough (1861)[note 4]

- Tilbury Nogo (1861)

- The Queen's Maries (1862)

- The Gladiators (1863)

- Brookes of Bridlemere (1864)

- Cerise (1866)

- The White Rose (1868)

- Bones and I, or The Skeleton at Home (1868)

- M. or N. (1869)

- Songs and Verses (Chapman and Hall, 1869) – several editions followed

- Contraband (1870)

- Sarchedon: A Legend of the Great Queen (1871)

- Satanella (1873)

- Uncle John (1874)

- Katerfelto (1875) – after a famous, possibly mythical, stallion on Exmoor in the early 19th century

- Sister Louise (1875)

- Rosine (1875)

- Riding Recollections (1878)[note 5]

- Roy's Wife (1878)

- Black but Comely (1879)[note 6]

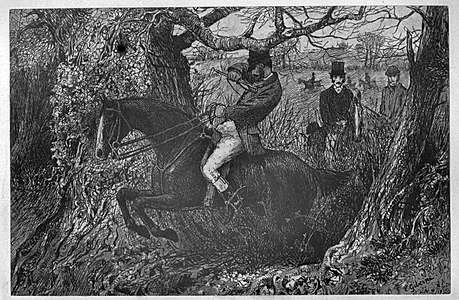

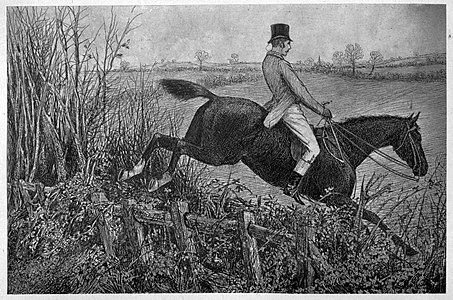

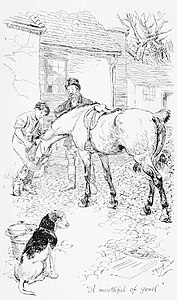

Example of illustrations for "Riding Recollections"[edit]

Whyte-Melville's "Riding Recollections", essentially a manual of horsemanship, was a popular work widely cited as an authority in the following decades. More than twenty years after his death the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News was recommending Riding Recollections to those who wanted to learn to really ride rather than just being carried by their horse saying that the every word of the book "breathes not only of the practised and practical horseman, but also of the love he bore for the noblest of all animals."[31] It ran to at least seven editions in the first year of publication.[32][note 8] The importance of Riding Recollections in White-Melville's output is signalled by it being selected as the first volume of a 24-volume deluxe edition of his work in 1898.[34] All of the volumes are available online at the British Library.[35]

Illustrations by Edgar Giberne (24 June 1850 – 21 September 1889) for the 1878 edition of "Riding Recollections" (Chapman and Hall, London) by Whyte-Melville (1821–1878) By courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library.[36]

-

Leaving brothers, husbands, even admirers, hopelessly in the rear

-

Teaching horses to jump timber

-

Give the bridle a hard tug

-

An easy place under a tree

-

Asking the way

-

At Bay

-

Half a dozen shrill blasts in quick succession

-

The King of the Golden Mines

The differences between the illustrations for the 1878 and the 1898 editions show how illustration had changed in the late 1800s. Illustrations by Hugh Thomson (1 June 1860 – 7 May 1920) for the 1898 edition of "Riding Recollections" (W. Thacker, London) by Whyte-Melville by courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library.[6]

-

Half a dozen shrill blasts

-

Choking a narrow hand gate

-

Watching his performances from the road

-

Handing his horse over

-

Accept the ridicule, and grasp the mane

-

Breaking the top rail with a hind hoof

-

I've spoilt my hat, I've torn my cloak

-

This strangely equipped pair

-

The old coachman piloting her children

-

While you smoke a cigar

-

A mouthful of gruel

-

Poised in air

Notes[edit]

- ^ The official prices of a Captain's commission in an infantry regiment like the 93rd highlanders was £1,800 plus the "regimental value", which could vary between half and twice the official price. The official price for a Lieutenant's commission in a Foot Guards regiment like the Coldstream Guards (which bore the army rank of Captain) was £2,050.[7] However as this was a more fashionable regiment, it probably had a higher "regimental value", and Whyte-Melville might have had to pay cash in the exchange of commissions.

- ^ Whyte-Melville's widow had no better luck with her second marriage, to Henry Higginson, "a shady and drunken American", who absconded to Norway with the widow's companion, the novelist Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright (14 December 1859 – 12 August 1945), possibly with some of the widow's funds.[8]: 113

- ^ This novel was based on Whyte-Melville's experience in the Crimean War[29]

- ^ The Morning Post said that Market Harborough was "universally recognised as the best hunting novel ever written".[21]

- ^ While the list of publications by Whyte-Melville in the 1898 edition give 1875 as the date of publication of the book,[6]: xix the Pall Mall Gazette advertised the book in February 1878 as a "New Work by Major Whyte Melville" that would shortly be ready.[30]

- ^ The "complete list" of publications given in the 1898 edition of "Riding Recollections" notes that the publication was posthumous.[6]: xix

- ^ Distributing the type meant that the type was removed from the forms used for printing and distributed back into the typesetters bins.

- ^ Although the publisher called these editions, imprints would be a more correct title. The book cost 12 shillings on publication,[33] and the edition size was probably of the order of 1,000 copies. It was reprinted in 1898 in an edition of 1,350 copies, for which the type was distributed after the edition was printed[note 7] after printing.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ All Poetry. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b c d e "MR. J. G. WHYTE MELVILLE". The Empire. Sydney: National Library of Australia. 2 September 1867. p. 2. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ "The Lee family, boatbuilders of Tweedmouth". Friends of Berwick and District Museum and Archives (berwickfriends.org.uk).

- ^ a b c Hinings, Jessica (23 September 2004). "Melville, George John Whyte (1821–1878)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29343. Retrieved 1 November 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Whyte-Melville, George John (1898). Riding Recollections. London: W. Hacker & Co. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ Armatys, John; Cordery, Robert George (2005). "The Purchase of Officers' Commissions in the British Army". Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b Kemp, Sandra; Mitchell, Charlotte; Trotter, David (1997). Edwardian Fiction: An Oxford Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811760-5. Retrieved 26 June 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "Police: Marylebone". The Times (Saturday 14 July 1849): 8. 14 July 1849. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "The Police Courts: Marylebone". The Daily News (Saturday 14 July 1849): 7. 14 July 1849. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Metropolis: Perjury in a Case of Affiliation". Hampshire Advertiser (Saturday 28 July 1849): 6. 28 July 1849. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Whyte-Melville, George John". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 617–618.

- ^ Nield, Jonathan (1925), A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales. G. P. Putnam's sons (p. 17).

- ^ Thomas Seccombe, revised by James Lunt. "Smart, Henry Hawley (1833–1893)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (ODNB). Retrieved 15 January 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Sutherland, John (1989). The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1528-9. Retrieved 5 August 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Drabble, Margaret, ed. (1985). The Oxford Companion to English Literature (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866130-6. Retrieved 1 November 2020 – via The Internet Archive.

- ^ Whyte Melville, George John (September–December 1876). "The Object of a Life". Temple Bar. London: William Clowes and Sons. p. 514. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Wills and Probates 1858-1996: Pages for Melville and the year of death 1879". Find a Will service. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Henry, Frank (1914). Members of the Beaufort hunt, past & present. Cirencester: Standard Printing Works. pp. 1–80.

- ^ "Death of Major Whyte Melville". Dublin Evening Mail (Monday 9 December 1878): 4. 9 December 1878. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Sporting Intelligence". Morning Post (Monday 9 December 1878): 2. 9 December 1878. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Whyte-Melville Memorial Fountain" Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Visit St Andrews.

- ^ "Whyte-Melville Fountain". UK Attraction.

- ^ "Plans in full flow to return water to fountain". The Saint.

- ^ "Water flows again through fountain in heart of St Andrews" Archived 17 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Fife Today.

- ^ Sutcliff, Rosemary (1983). Blue Remembered Hills. Handheld Press. p. 138. ISBN 9781912766802.

- ^ Houghton, Walter E. (24 May 2013). Index to Victorian Periodicals 1804–1900. Routledge. pp. 414–18. ISBN 978-1135795504. The Autobiography of Captain Digby Grand was published in Fraser's Magazine from November 1851 to December 1852.

- ^ Houghton, Walter E. (24 May 2013). Index to Victorian Periodicals 1804–1900. Routledge. pp. 422–26. ISBN 978-1135795504. General Bounce was published in Fraser's Magazine, January–December 1854.

- ^ Baker, Earnest A. (1914). A guide to Historical Fiction. London: George Routledge & Sons Ltd. p. 161. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "Chapman & Hall's Publications". Pall Mall Gazette (Thursday 7 February 1978): 16. 7 February 1878. Retrieved 30 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Sportsman's Library". Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (Saturday 10 March 1900): 24. 10 March 1900. Retrieved 3 November 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Siuitable for Presents: Major Whyte-Melville's Works". The Field (Saturday 14 December 1878): 14. 14 December 1878. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Chapma & Hall's Publications". Pall Mall Gazette (Friday 20 December 1878): 16. 20 December 1878. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Whyte-Melville in Buckram". Pall Mall Gazette (Wednesday 19 October 1898): 4. 19 October 1898. Retrieved 31 October 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Whyte-Melville, George John; Maxwell, H. (1898–1902). The works of G. J. Whyte-Melville edited by Sir H. Maxwell. Vol. 24 volumes. London: W. Thacker % Co. Retrieved 1 November 2020 – via The British Library.

- ^ Whyte-Melville, George John (1878). Riding Recollections (5th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

External links[edit]

- Works by George John Whyte-Melville at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Whyte-Melville at Internet Archive

- G. J. Whyte-Melville at Library of Congress, with 49 library catalogue records

- Guide to the G.J. Whyte-Melville Collection circa 1860s at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center