Ottoia

| Ottoia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

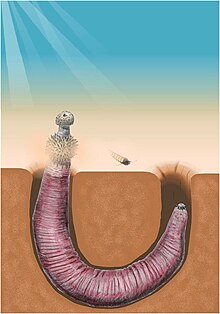

| Reconstruction of Ottoia prolifica. | |

| |

| The anterior portion of Ottoia, illustrating annulation and the eversible proboscis. From Smith et al. (2015)[2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Stem group: | Priapulida (?) |

| Family: | †Ottoiidae Walcott, 1911 |

| Genus: | †Ottoia Walcott, 1911 |

| Species | |

| |

Ottoia is a stem-group archaeopriapulid worm known from Cambrian fossils.[3] Although priapulid-like worms from various Cambrian deposits are often referred to Ottoia on spurious grounds, the only clear Ottoia macrofossils come from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, which was deposited 508 million years ago.[1] Microfossils extend the record of Ottoia throughout the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, from the mid- to late- Cambrian.[1] A few fossil finds are also known from China.[4]

Morphology[edit]

Ottoia specimens are on average 8 centimeters in length. Both length and width show variation with contraction; shorter specimens often being wider than longer ones. The characteristic proboscis of priapulids is present at the anterior, attached to the trunk of the animal, proceeded by the "bursa" at the posterior. The organism's body is bilaterally symmetrical, however, its anterior displays external radial symmetry. Like some other modern invertebrates, a cuticle restricts the size of and protects the animal.

The trunk hosts the internal organs of the organism, divided into seventy to a hundred annulations of varying spacing, depending on curvature and contraction. The posterior displays a series of hooks, which likely acted as anchors during burrowing. Muscles support the animal and retract the bursa and proboscis. A gut leading from the anus in the bursa to the mouth in the proboscis runs through the trunk's spacious body cavity, and a concentration of gut muscles serve the function of a gizzard. A nerve chord runs down the organism's length. In addition to the other organs, it is possible Ottoia contained urogenital organs in its trunk. There is no evidence of a respiratory organ, though the bursa may have served this purpose.[5]

The everted proboscis of Ottoia bears an armature of teeth and hooks. The detailed morphology of these elements distinguishes the two described species, O. tricuspida and O. prolifica.[1] At the base of the pharynx, separated from the teeth by an unarmed region, sits a ring of spines. Behind this, at the front of the trunk, lies a series of hooks and spines, arranged in a quincunx pattern like the five dots on a domino or dice.[1]

Ecology[edit]

Ottoia was a burrower that hunted prey with its eversible proboscis.[6] It also appears to have scavenged on dead organisms such as the arthropod Sidneyia.[7]

The spines on the proboscis of Ottoia have been interpreted as teeth used to capture prey. Its mode of life is uncertain, but it is thought to have been an active burrower, moving through the sediment after prey, and is believed to have lived within a U-shaped burrow that it constructed in the substrate. From that place of relative safety, it could extend its proboscis in search of prey. Gut contents show that this worm was a predator, often feasting on the hyolithid Haplophrentis (a shelled animal similar to mollusks), generally swallowed them head-first. They also show evidence of cannibalism, which is common in priapulids today.

Preservation[edit]

Because of its bottom-living habit and the location of the Burgess Shale site at the foot of a high limestone reef, one may presume the relative immobility of Ottoia placed it in danger of being carried away and/or buried by any underwater mud avalanche from the cliff top. This may explain why it remains one of the more abundant specimens of the Burgess Shale fauna.

Distribution[edit]

At least 1000 Burgess Shale specimens are known in the UNSM collections alone,[5] in addition to the ROM collections and hundreds of specimens elsewhere. 677 specimens of Ottoia are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 1.29% of the community.[8]

Ottoia has also been reported from Middle Cambrian deposits in Utah and Spain,[9] Nevada,[10] and various other localities.[11] Nevertheless, these reports are insecure, and the only verifiable Ottoia macrofossils herald from the Burgess Shale itself.[1]

Microfossils corresponding to Ottoia teeth, however, have a much broader distribution, and are found throughout the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin.[1] Indeed, putative candidates (initially described under the ICBN as Goniomorpha) may extend the range of Ottoia, or at least similar priapulans, into the Ordovician.[12]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Smith, M. R.; Harvey, T. H. P.; Butterfield, N. J. (2015). "The macro- and microfossil record of the Cambrian priapulid Ottoia" (PDF). Palaeontology. 58 (4): 705–721. Bibcode:2015Palgy..58..705S. doi:10.1111/pala.12168.

- ^ Smith MR, Harvey THP, Butterfield NJ(2015) Data from: The macro- and microfossil record of the middle Cambrian priapulid Ottoia. Dryad Digital Repository. doi:10.5061/dryad.km109

- ^ Budd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 253–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x. PMID 10881389. S2CID 39772232.

- ^ "Miaobanpo section (Orytocephalus indicus zone) - Kaili Fm (Cambrian of China)". PBDB.

- ^ a b Conway Morris, S (1977). "Fossil priapulid worms". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 20.

- ^ Vannier, Jean (August 2009). "The Gut Contents of Ottoia (Priapulida) from the Burgess Shale: Implications for the Reconstruction of Cambrian Food Chains" (PDF). In Smith, Martin R.; O'Brien, Lorna J.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (eds.). Abstract Volume. International Conference on the Cambrian Explosion (Walcott 2009). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: The Burgess Shale Consortium (published 31 July 2009). ISBN 978-0-9812885-1-2.

- ^ Bruton, D. L. (2001). "A death assemblage of priapulid worms from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale". Lethaia. 34 (2): 163–167. Bibcode:2001Letha..34..163B. doi:10.1080/00241160152418456.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. Bibcode:2006Palai..21..451C. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022. S2CID 53646959.

- ^ Conway Morris, S.; Robison, R. A. (1986). "Middle Cambrian priapulids and other soft-bodied fossils from Utah and Spain" (PDF). University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions. 117: 1–22. hdl:1808/3696.

- ^ Lieberman, B. S. (2003). "A New Soft-Bodied Fauna: the Pioche Formation of Nevada". Journal of Paleontology. 77 (4): 674–690. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<0674:ANSFTP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Supplementary Information used to be available in: doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3052.4328

- ^ Shan, Longlong; Harvey, Thomas H.P.; Yan, Kui; Li, Jun; Zhang, Yuandong; Servais, Thomas (2023). "Palynological recovery of small carbonaceous fossils (SCFS) indicates that the late Cambrian acritarch Goniomorpha Yin 1986 represents the teeth of a priapulid worm". Palynology. 47 (3). Bibcode:2023Paly...4757504S. doi:10.1080/01916122.2022.2157504. S2CID 254711455.

External links[edit]

- "Ottoia prolifica". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12.

- Ottoia prolifica (A priapulid worm) from the Smithsonian Institution.

- Ottoia prolifica from the Hooper Virtual Paleontological Museum (HVPM)